FEDS Notes

May 03, 2024

Estimating the importance of monetary policy shocks for variation in the U.S. homeownership rate1

Daniel Dias and Joao Duarte

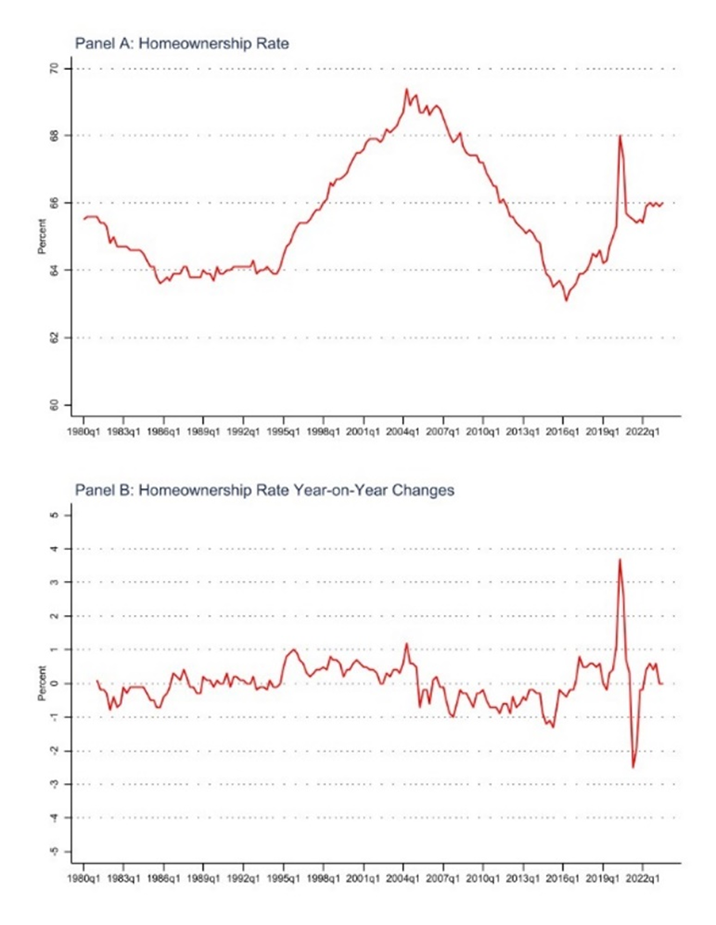

Being a homeowner is one of the tenets of the American dream. In general, relative to renting, people see homeownership as a path to wealth through the usual appreciation of the house prices and the forced savings through mortgage payments but also a path to financial stability through more stable and predictable housing costs (Young et al., 2023). Homeownership also has some disadvantages relative to renting, these include unexpected maintenance costs, high transaction costs related to the buying and selling of properties and decline in property value due to exogenous factors such as increased criminality, climate change, or higher taxes. As shown in panel A of Figure 1, the U.S. homeownership rate has hovered around 66% in the last 30 or so years – this means that about 2 out of every 3 households in the United States own the house they live in, while about 1 of every 3 households rents.

Source: St. Louis Fed FRED database and author's calculations.

While the homeownership rate in the United States has fluctuated within a relatively narrow range since the 1980s, there have been significant swings in this variable. As can be seen in Panel A of Figure 1, the U.S. homeownership increased from about 64 percent in 1995 to a little over 69 percent in 2004, and then fell to a low of 63 percent in mid-2016. There can be several factors explaining short-term variation in the U.S. homeownership rate. One such factor, as shown in Dias and Duarte (2019), is monetary policy. In Dias and Duarte (2019), we provided evidence that more people tend to rent when monetary policy tightens, while more people tend to own when monetary policy loosens. We interpreted these results as evidence that monetary policy affects households' decision to buy or to rent. In a more recent paper, Dias and Duarte (2022), we found that monetary policy shocks can be an important driver of fluctuations in the homeownership rate.2 In this note, we summarize and update the results of Dias and Duarte (2022) to provide estimates of the importance of monetary policy shocks for variation in the U.S. homeownership rate.

Methodology and Data

In the empirical application presented in this note, we use two complementary state-of-art methodologies for better robustness of results. We estimate a vector autoregressive (VAR) model and identify the monetary policy shocks using an external instrument as described in Plagborg-Moller and Wolf (2021) – the authors refer to this method as the "internal instrument" procedure (SVAR-IV). In addition, we estimate a structural vector moving average with instrumental variables (SVMA-IV), as proposed by Plagborg-Moller and Wolf (2022), to get estimates of the importance of monetary policy shocks under milder identification assumptions than those needed in the case of the structural VAR model.3

In the estimation of the empirical models, we use seven macroeconomic variables – the effective federal funds rate, real GDP growth, CPI growth, the excess bond premium, year-on-year changes of the homeownership rate, quarterly changes in house prices, and quarterly changes in house rents – at a quarterly frequency for the period 1991:Q1 to 2019:Q2. All these variables were obtained from the St. Louis Fed FRED database. To implement the two empirical methodologies, we also need an external instrument for monetary policy shocks, and for this matter we chose to use the Jarocinsky and Karadi (2022) monetary policy instrument, which controls for the information channel of monetary policy.

Results and Discussion

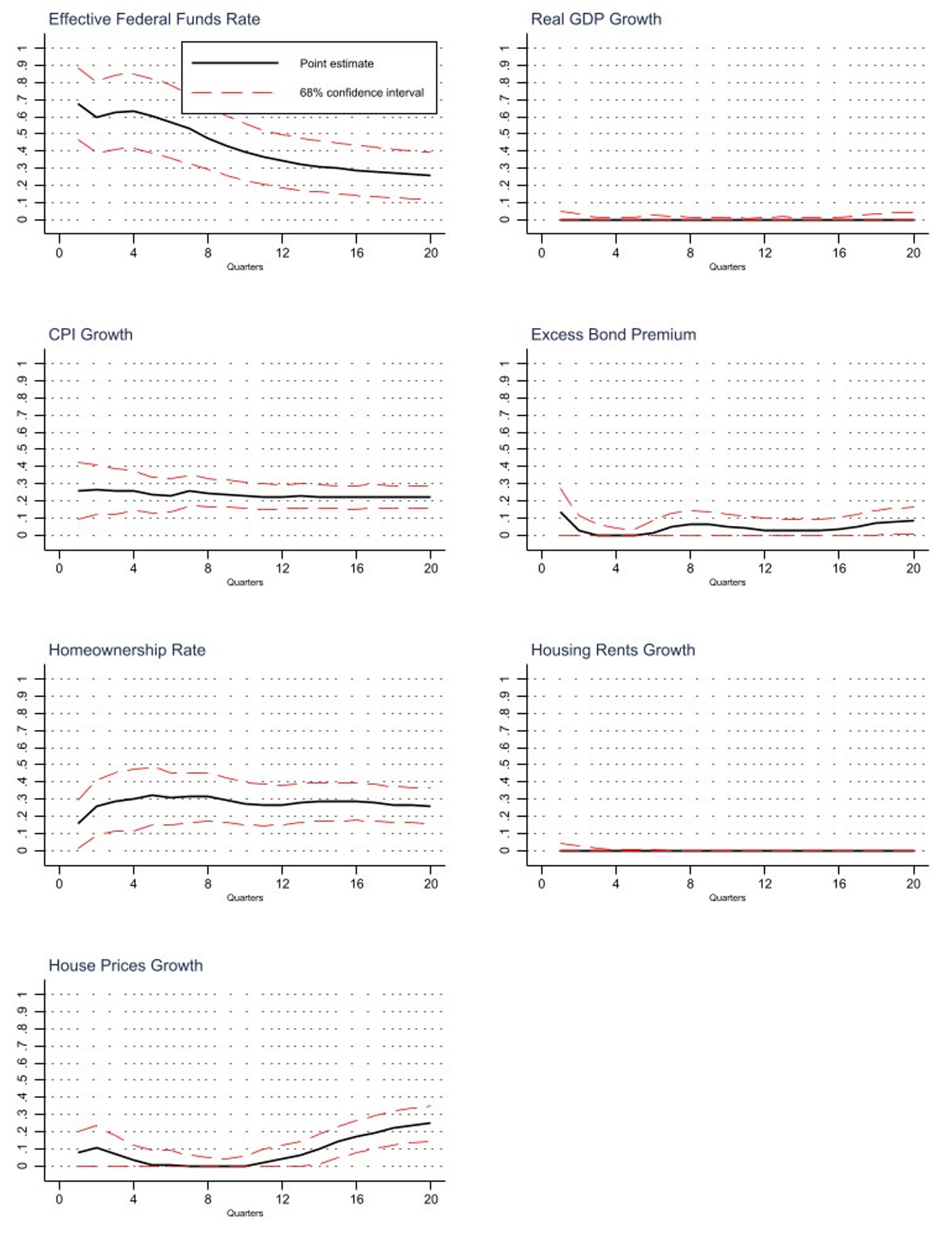

The first set of results, shown in Figure 2, pertains to the analysis based on the SVAR-IV model.

Figure 2. Contribution of Monetary Policy Shocks to the Variation of Selected Macroeconomic Variables based on SVAR-IV approach

Note: Dashed lines denote 68% confidence intervals.

Source: Author's calculations.

Starting with the homeownership rate, according to the results in Figure 2, monetary policy shocks account for about 15 percent of the variation of the homeownership rate in the first quarter after a shock, but this ratio rises to around 30 percent in the second quarter and remains at this level thereafter. For comparison, according to this methodology, monetary policy shocks account for about 30 percent of the variation in CPI growth, which means that based on this methodology, monetary policy shocks are as important for variations in the growth rate of the CPI as they are for variations in the homeownership rate. As for real GDP growth, based on this method, we estimate that monetary policy shocks have almost no bearing on the variation of real GDP growth. For the other variables in the model, we note that based on this methodology, we estimate that monetary policy shocks have almost no bearing on the variation of housing rents growth, but explain up to 30 percent of the long-run variation in house prices growth.

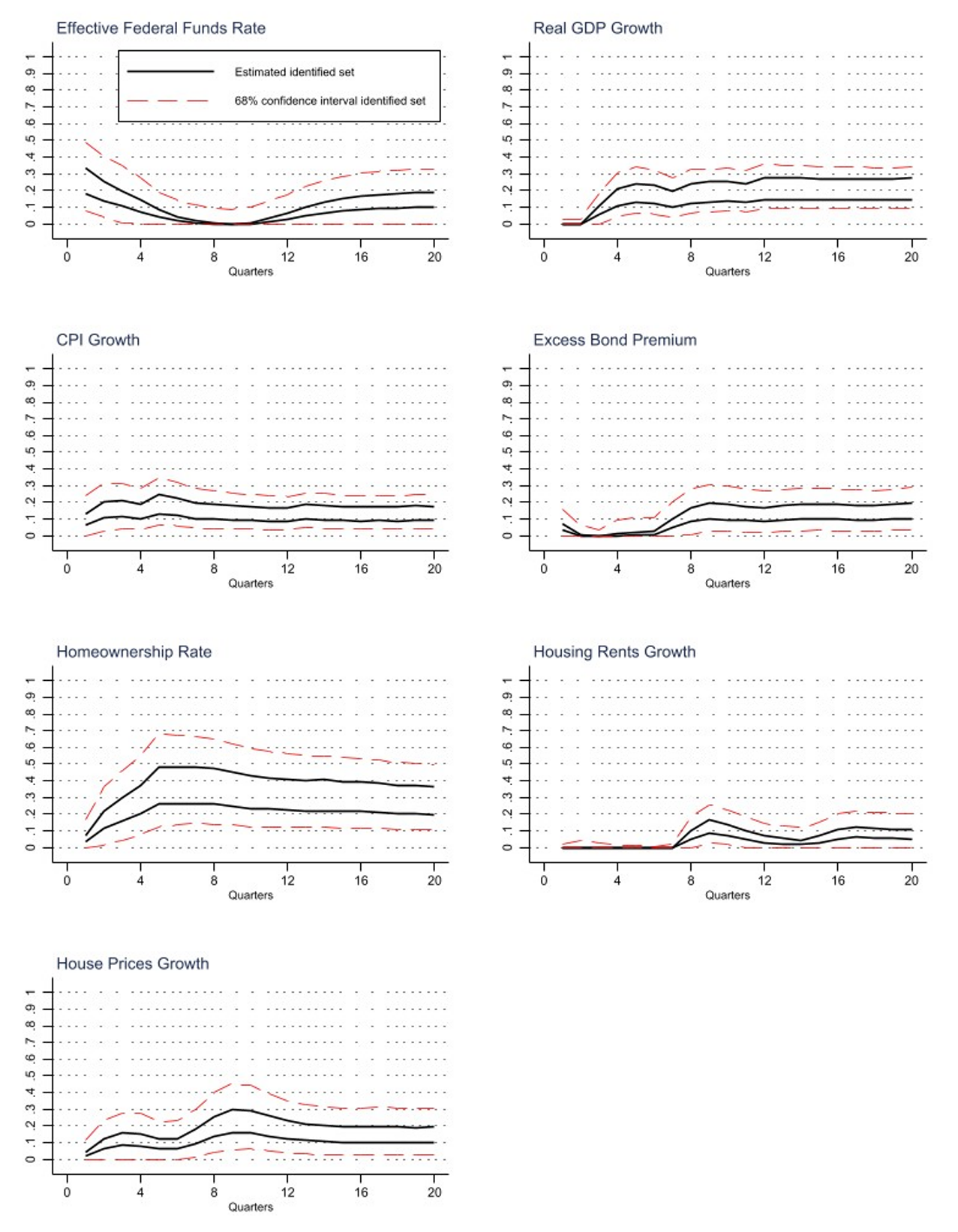

Turning now to the results based on the SVMA-IV approach, shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Contribution of Monetary Policy Shocks to the Variation of Selected Macroeconomic Variables based on SVMA-IV approach

Note: Dashed lines denote 68% confidence intervals for the identified set.

Source: Author's calculations.

Based on this methodology, we get similar results to those based on the SVAR-IV in some cases, but in other cases, we get noticeably different results. Starting again with the homeownership rate, based on the SMVA-IV approach, we estimate that monetary policy shocks have a small effect on the variation of the homeownership rate in the short-run, but that this ratio rises to between 20 and 40 percent in the medium run, stabilizing thereafter around 30 percent. These results are very much in line with those we had obtained using the SVAR-IV approach. As for CPI growth, this methodology estimates that monetary policy shocks account for less than 20 percent of the variation in CPI growth, a result that is somewhat lower than that based on the SVAR-IV methodology. All in all, when we compare the results for the homeownership rate and CPI growth based on the two methodologies, we conclude that monetary policy shocks are at least as important for variation in the U.S. homeownership rate as they are for variation in CPI growth and this importance is significant.

Unlike what we found using the SVAR-IV approach, based on the SVMA-IV approach, we estimate that monetary policy shocks account for as much as 20 percent of the medium- and long-term variation in real GDP growth. As for housing rents, based on the SVMA-IV approach, we estimate that monetary policy shocks account for as much as 20 percent of the medium-term variation in rents, and just about 10 percent of the long-term variation of this variable. For house prices, we find a similar result to that based on the SVAR-IV approach, which is that monetary policy shocks account for between 10 percent and up to 30 percent of the variation in house prices growth.

Taking together the results for the housing market variables (homeownership rate, housing rents, and housing prices) based on the two methodologies, we provide further evidence that monetary policy shocks are an important driver of fluctuations in the housing market, including fluctuations in households' decision to own or rent the house they live in.

Concluding Remarks

There is ample evidence that monetary policy, or changes in credit conditions more generally, has substantial effects on the housing market, but these results have been mostly focused on house prices and housing construction (see, for example, Favara and Imbs, 2015, or Piazzesi and Schneider, 2016). Recent work has shown that frictions in the housing market, namely with respect to the ability to adjust the supply of housing for rental and owner-occupied housing, transmit monetary policy and/or changes in credit conditions in unexpected ways (see Greenwald and Guren, 2021, or Dias and Duarte, 2022). This note summarizes some of our previous work (Dias and Duarte, 2019, and Dias and Duarte, 2022) and provides evidence on the importance of monetary policy shocks to the homeownership rate, vis-à-vis, to household homeownership decisions. One such effect, as shown in Dias and Duarte (2022), is that the distributive effects of monetary policy get amplified when a housing tenure choice is at play. Moreover, given the importance of homeownership for wealth accumulation, especially for middle- and lower-income households, fluctuations in the homeownership rate can have significant effects on households' wealth accumulation dynamics, which in turn can affect consumption dynamics over the life cycle. To the extent that some of the fluctuations in the homeownership rate are driven by monetary policy, it means that monetary policy decisions may have effects that go beyond the typical business cycle duration. In Dias and Duarte (2022), we explore some of the implications of the effect of monetary policy for housing tenure decisions and suggest ways to dampen these effects.

References:

Dias, D. A., & Duarte, J. B., 2019, "Monetary policy, housing rents, and inflation dynamics", Journal of Applied Econometrics, 34(5), 673-687.

Dias, D. A., & Duarte, J. B., 2022. "Monetary policy and homeownership: Empirical evidence, theory, and policy implications", International Finance Discussion Paper, (1344).

Favara, G., & Imbs, J., 2015, "Credit supply and the price of housing", American Economic Review, 105(3), 958-992.

Greenwald, D. L., & Guren, A., 2021, "Do credit conditions move house prices?", National Bureau of Economic Research WP#29391.

Jarociński, M., & Karadi, P., 2020, "Deconstructing monetary policy surprises—the role of information shocks", American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 12(2), 1-43.

Piazzesi, M., & Schneider, M., 2016, "Housing and macroeconomics", Handbook of macroeconomics, 2, 1547-1640.

Plagborg‐Møller, Mikkel, & Wolf, C. K., 2021, "Local projections and VARs estimate the same impulse responses", Econometrica, 89.2, 955-980.

Plagborg-Møller, Mikkel, & Wolf, C. K., 2022, "Instrumental variable identification of dynamic variance decompositions", Journal of Political Economy, 130.8 , 2164-2202.

Young, C., Zinn, A, & Choi, J. H., 2023, "Rethinking Homeownership as the "American Dream", Urban Institute, Urban Wire, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/rethinking-homeownership-american-dream

1. By Daniel A. Dias, Federal Reserve Board, and João B. Duarte, Nova School of Business and Economics. Return to text

2. Note that monetary policy shocks and monetary policy stance are related but distinct. Shocks are unexpected interest rate changes, while the stance is the central bank's goal: stimulating growth and increasing inflation (expansionary) or cooling the economy and reducing inflation (contractionary). Return to text

3. When using the SVAR-IV model to estimate the importance of shocks for a given variable, we need to assume that the model is invertible. That is, that we can use the observed data to accurately infer the unobserved components or shocks of the model. When using the SVMA-IV model, we don't need to make such an assumption, but, without making further assumptions about the underlying structural model, we can only estimate intervals for the importance of a shock for the variability of a variable. Return to text

Dias, Daniel A., and Joao B. Duarte (2024). "Estimating the importance of monetary policy shocks for variation in the U.S. homeownership rate," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May 03, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3457.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.