FEDS Notes

October 18, 2017

The Increased Role of the Federal Home Loan Bank System in Funding Markets, Part 1: Background1

Stefan Gissler and Borghan Narajabad

Executive Summary

The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system was founded in 1932 to support mortgage lending by thrifts and insurance companies. Over time, the system has grown into a provider of funding for a larger range of financial institutions, including commercial banks and insurance companies. During the early part of the last financial crisis, the FHLB system played an important stabilizing role as a "lender of next-to-last resort" by providing funding--collateralized by mortgages and mortgage related assets--to banks, thrifts, insurance companies, and credit unions. However, developments over the past few years have increased the tail risks that FHLBs pose to the financial system. Part 1 of this note provides an overview of the FHLB system. Part 2 highlights some of the recent developments in the FHLB system. And part 3 discusses the implications of these developments for financial stability.

FHLBs have grown significantly over the past few years, and their total assets have surpassed pre-crisis levels. More recently, this growth coincided with two changes in government policies: The imposition of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) in January 2015 for the largest U.S. banking organizations and the reform of U.S. money market funds in 2016. The preferential treatment in the LCR of medium-term borrowing from FHLBs has given large banking institutions an incentive to borrow more from FHLBs and less from private short-term money markets. As large banking institutions have increased term borrowing from FHLBs, the FHLBs have, in turn, increased their own reliance on short-term borrowing from money markets, thereby increasing the maturity transformation implicit in their financial activities.

Although FHLB's use of short-term funding has been trending up for several years, it appears to have been supported more recently by the final implementation of the money fund reform. The reform caused about $1.2 trillion to shift from prime money funds--which provide direct funding to large banking institutions and other firms--to government money funds--which cannot fund banks directly but can fund the FHLBs that do. Indeed, government money funds currently hold more than half of all outstanding debt issued by FHLBs.

The FHLBs have long been considered relatively safe intermediaries because their loans to private member institutions are over-collateralized, they can jump to the front of the line when a borrower defaults--the so-called "super lien" of their loans--and they benefit from an implicit government guarantee investors appear to associate with federal agencies. Moreover, changes to prudential regulations such as the revised risk-based capital requirements and stress tests have likely made the FHLBs more resilient.

However, their increasing maturity transformation, combined with their high leverage, leave the FHLBs more vulnerable to shocks--an issue that has been highlighted recently by the regulatory authority of the FHLB system, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA).2 Further, FHLBs' recent growth has increased the financial system's reliance on FHLB funding as well as the interconnectedness of the financial system, suggesting that distress among the FHLBs could be transmitted broadly to other firms and markets.

Historical background and key institutional characteristics

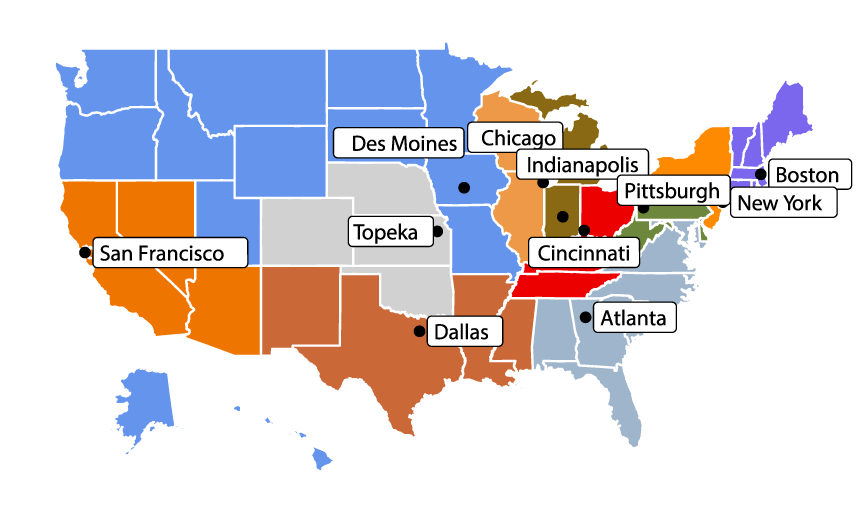

The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system was created by the FHLB Act of 1932 to help the mortgage market. The system began with 12 independent, regional wholesale banks and the national Office of Finance, which is the system's centralized debt issuance facility.3 FHLBs, as government-sponsored entities, are perceived to have implicit backing from the government. In addition, the U.S. Treasury is authorized to purchase up to $4 billion of FHLB System debt securities. Each FHLB is owned by its member institutions, which have equity stakes in the FHLB and must reside in the FHLB's district (Figure 1).4 Members were initially limited to thrifts and insurance companies, which at the time had limited access to wholesale funding in private markets.

Source: FHFA.

In response to the Savings and Loan crisis, the Financial Institutions Recovery, Reform, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) of 1989 opened FHLB membership to all depository institutions holding more than 10 percent of their assets in residential mortgage-related assets. As a result, many commercial banks and credit unions joined the FHLB system. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 attempted to make the system's capital structure more permanent, mainly by requiring a five-year redemption notice before a member can retrieve its equity stake in its FHLB.5

Since 2008, the FHLB system has experienced two key structural changes. First, the Housing and Economic Reform Act of 2008 established the FHFA and put it in charge of regulating the FHLB system. Second, following the FHLB Seattle's losses on its securities investment, the bank was merged into FHLB Des Moines after several unsuccessful attempts to restore FHLB Seattle's capital.6 Hence, the system currently comprises 11 FHLBs and the Office of Finance.

FHLBs provide wholesale funding for their members' mortgages and mortgage-related investments by extending over-collateralized loans, known as advances upon request by members. These over-collateralized loans are available in various maturities with either fixed or variable interest rates and may include embedded options. Each FHLB independently chooses the interest rates of its advances and the haircuts on its members' collateral. But, all FHLB advances are subject to the statutory super-lien, which means that in the case of the borrower's insolvency, any security interest granted to an FHLB has priority over the claims and rights of any other party.7 The super-lien on collateral has facilitated FHLBs' ability to lend to a variety of institutions, from subsidiaries of large insurance and bank holding companies to small saving banks and credit unions that might otherwise not have ready access to funding from investors who cannot secure such protection.

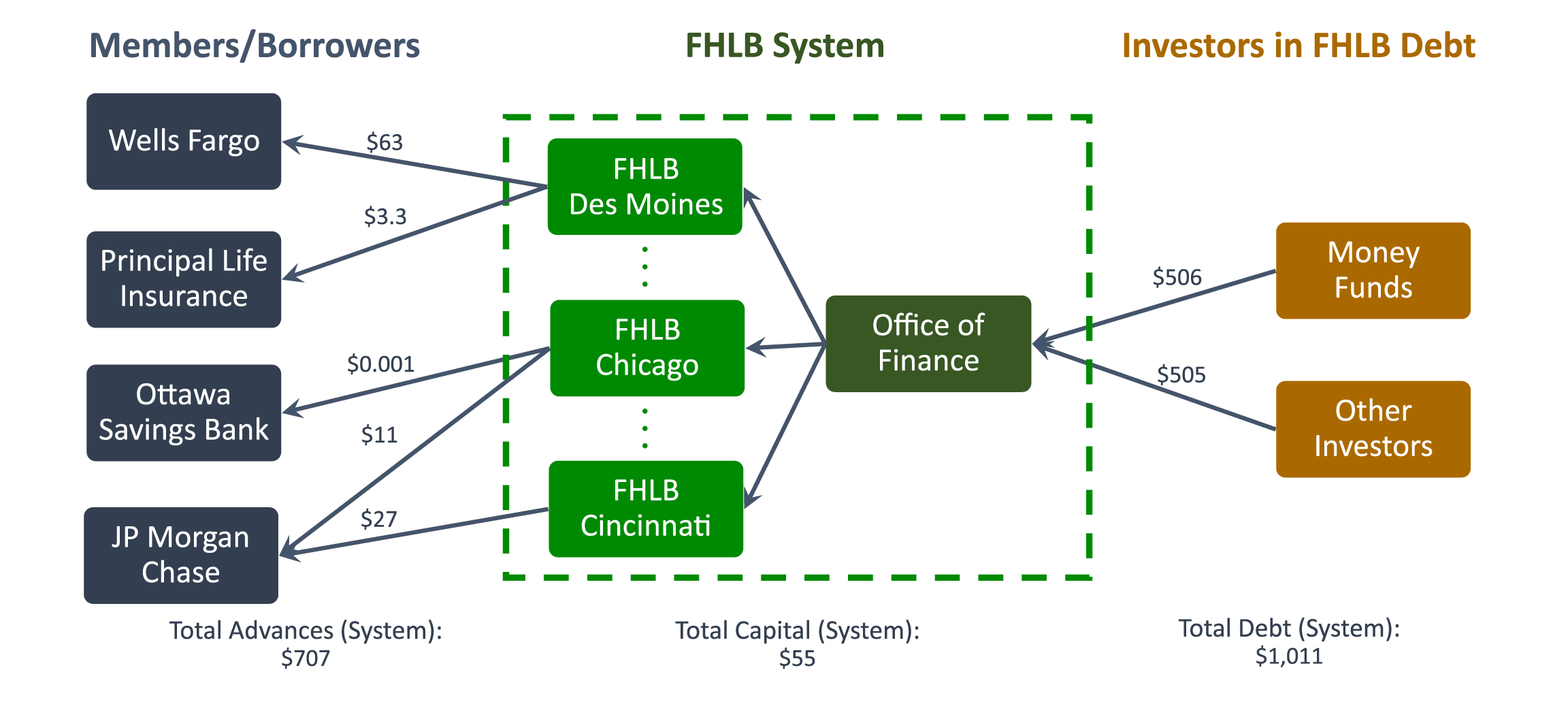

FHLBs are highly leveraged financial institutions, with a capital level of about 5 percent of their assets. FHLBs' advances and other assets are funded by consolidated debt obligations. These consolidated obligations are joint and several liabilities, meaning that if an individual FHLB cannot repay it, then the other 10 FHLBs are liable to cover its debt. Also, investors cannot know which individual FHLB is receiving their money, because all debt is issued by a single entity, the Office of Finance. Moreover, FHLBs' status as GSEs helps to ensure that funding costs for FHLBs are relatively low. The flow of funds from investors, such as money funds, to members of FHLBs is shown in Figure 2. Arrows denote the direction of lending. For example, money funds held $506 billion of FHLB-system debt at the end of last year, and FHLB Des Moines issued $63 billion of advances to Well Fargo.

*All amounts in billions of dollars, as of June 2017

Source: FHLB 10Q and 10K filings, SEC N-MFP filings, CALL reports.

Part 2 in this series discusses recent trends in the FHLB system and potential drivers of those trends.

1. Authors: Stefan Gissler and Borghan Narajabad (R&S). We would like to thank Alice Moore and Erin Hart for their research assistance, and Celso Brunetti, Mark Carlson, Burcu Duygan-Bump, Joshua Gallin, Diana Hancock, Lyle Kumasaka, Andreas Lehnert, Laura Lipscomb, Patrick McCabe, Michael Palumbo, John Schindler, and Lane Teller for useful comments and insightful discussions. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or its staff. Return to text

2. See, for example, prepared remarks of Melvin L. Watt, Director of FHFA at 2017 Federal Home Loan Bank Directors' Conference (5/23/2017): https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/Prepared-Remarks-of-Melvin-L-Watt-Director-of-FHFA-FHLBank-Directors-Conference.aspx Return to text

3. The FHLB Board originally oversaw the system, but was abolished by the Financial Institutions Recovery, Reform, and Enforcement Act of 1989. Return to text

4. Note that the figure shows the current districts of the 11 remaining FHLBs, after FHLB Seattle's merger into FHLB Des Moines in 2015. Return to text

5. Until 1999, most of members' capital investment in FHLBs was subject to a six month redemption notice. Return to text

6. The merger occurred in 2015, after the FHFA rejected FHLB Seattle's capital restoration plans in 2009. Return to text

7. Super-lien gives FHLBs priority over the claims of depositors and almost all other creditors including the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Federal Reserve Banks (FRBs). Nevertheless, FRBs and FHLBs customarily work together to ensure that FRBs' retain their senior position with respect to collateral pledged to the FRBs by FHLB members. Return to text

Gissler, Stefan, and Borghan Narajabad (2017). "The Increased Role of the Federal Home Loan Bank System in Funding Markets, Part 1: Background," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 18, 2017, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2070.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.