IFDP Notes

December 3, 2013

The Long Road to Countercyclical Monetary Policy in Emerging Market Economies1

Brahima Coulibaly

During the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-09, central banks in both advanced and emerging market economies (EMEs) lowered policy rates to cushion the adverse shock and to spur economic activity. Likely because the reductions in rates were widespread and occurring more or less at the same time, it might have gone unnoticed that for EMEs in general, this was an unusual development.

Historically, EMEs had to raise interest rates during crises to contain capital flight and defend the value of their currencies. That is, monetary policy had traditionally been procyclical in the developing world, rather than countercyclical as in the advanced economies (AEs), depriving EMEs from using one of the main tools policymakers have to limit large cyclical and welfare-reducing swings in economic activity. In what follows, we review factors that likely enabled this outcome, assess to what extent EMEs can be expected to continue conducting countercyclical monetary policies, and analyze the recent developments in EMEs in the context of our findings.

More credible and flexible monetary policy frameworks promoted countercyclical policy

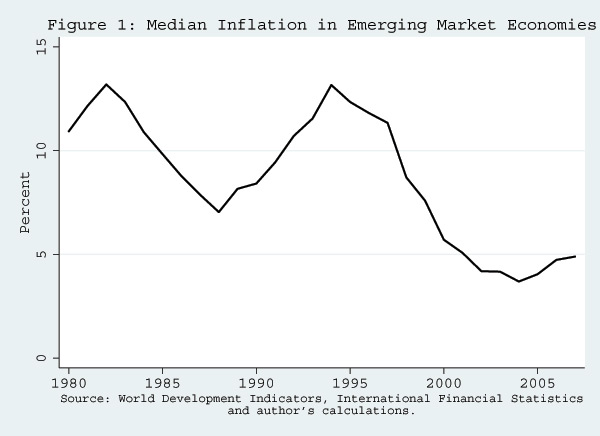

The abandonment of fixed exchange rate regimes in favor of relatively more flexible exchange rate regimes and more credible monetary policy frameworks, such as inflation targeting, were an important contributing factor in the ability to do countercyclical monetary policy during the GFC.2 In the 1980s, about three out of four EMEs had a pegged exchange rate regime. In the years leading to the crisis, the share had declined to less than one-half.3 Over the same period, several EMEs adopted inflation-targeting regimes. In the 1980s and early 1990s, no EME had an inflation-targeting regime in place, but by 2007, 16 of these economies did. More flexible exchange rate regimes removed the necessity to defend a particular value of the domestic currency and increased the ability of monetary policy to focus more on inflation and growth objectives. The increased credibility and effectiveness of policy contributed to lower and stabilize inflation and to anchor inflation expectations, which, in turn, enabled the use of countercyclical policy when growth prospects weakened during the GFC.

Sound macroeconomic management also facilitated the use of countercyclical policy

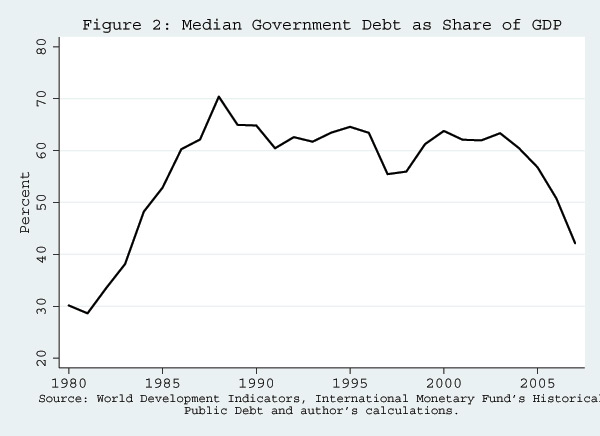

In addition, policymakers in EMEs made remarkable progress to reduce the vulnerabilities of the economies and to bolster their capacity to weather adverse shocks. Over the past decade or so, governments strived to significantly reduce debt-to-GDP ratios.

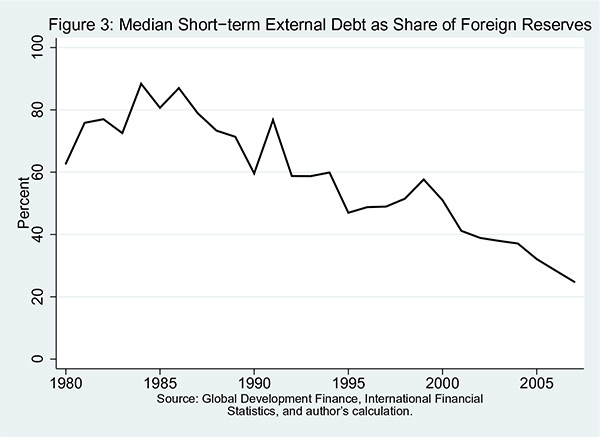

EMEs also made significant progress to reduce their dependence on foreign-currency-denominated debt, and to lengthen the maturities of their debts. Indeed, the adverse effect of a large depreciation on the balance sheets of the domestic economies, including the increase burden of servicing foreign-currency-denominated debt, was one of the main concerns that compelled EMEs to defend the exchange rate in periods of crises. With less reliance on foreign currency debt, that concern diminished. At the same time, less reliance on short-term debt helped reduce risks of large capital outflows and contain an increase in financing needs during periods of crises when investors are less inclined to roll over debt.

Notwithstanding the progress made on the policy front to reduce the vulnerabilities of their economies, EMEs also accumulated large amounts of foreign exchange reserves, which provide an extra cushion against adverse shocks. As a result, short-term external debt as a share of foreign exchange reserves declined from about 80 percent on average in the 1980s to 25 percent in 2007, which helped reassure foreign investors of the capacity of the EMEs to meet their external obligations.

All of these factors contributed to the shift from procyclical toward counterycyclical monetary policy in many EMEs. To be sure, past procyclical policies were not necessarily inappropriate under the circumstances. They could have been appropriate, but only as second-best responses to the crisis given, for example, the lack of policy credibility, the vulnerabilities of the economies, the fragile state of public resources, etc. With more flexible and credible monetary policy frameworks, stronger economic fundamentals, and lower vulnerabilities, EMEs were able to conduct countercyclical policies during the GFC. Using country-level panel and cross-section datasets from 1970 through 2009 and a logit regression model, I obtain results that support the importance of these factors in EMEs' ability to conduct countercyclical policy (see Coulibaly, 2012 for details).4

Nonetheless experience has varied across the EMEs and differences in vulnerabilities across countries continue to matter

It could be argued that the global financial crisis originated in AEs and that EMEs might not be able to lower policy rates during a homegrown crisis. Or that the ability of EMEs to lower policy rates during the crisis was facilitated by reductions in rates in the AEs, which helped to contain capital flight, to some extent, by maintaining a relatively stable interest rate differential between the two sets of countries.

However, not all EME policymakers were able to lower their policy rates. Several countries in emerging Europe, for example, raised them. This suggests that the origin of the GFC being in the AEs was not the main determining factor. Moreover, on the eve of the GFC, exchange rate regimes and monetary policy frameworks were less flexible in the countries that could not lower rates; except for Hungary, none of them had an inflation-targeting framework. Also, in these countries, inflation was generally higher, as was the share of short-term debt as a percent of foreign exchange reserves. Currency mismatches had also risen significantly in many of them, and current accounts often showed large deficits. More recently, as some EMEs have experienced financial stress since May of this year, investors also appear to be distinguishing between EMEs according to their relative vulnerabilities with the most vulnerable countries experiencing a greater deterioration in financial conditions.

It is also noteworthy that in the immediate aftermath of the GFC crisis, many EMEs adjusted policy rates countercyclically in response to developments in their respective economies, even as policy rates in the AEs remained about unchanged at low levels. That being said, EMEs' ability to conduct countercyclical policy will likely remain constrained to some degree by some of their remaining vulnerabilities and, in globally integrated financial markets, by developments abroad. For example, since early this year, several EMEs tightened monetary policy or refrained from loosening it further partly because of concerns over capital outflows, despite weak domestic economic growth. Nonetheless EMEs have made substantial progress on the policy front and they remain, on the whole, in a better position to pursue countercyclical monetary policy than they were during the 1980s and 1990s. To sustain this progress they will need to continue to foster good practices and quickly address any buildups in vulnerabilities.

1. Emerging market economies is defined broadly to include emerging market economies and developing countries. Return to text

2. To be clear, exchange rates in EMEs are still not as flexible as in the advanced economies, but they are generally more flexible than in the past. Return to text

3. Based on author's calculations using the International Monetary Fund data on exchange rate regimes. Return to text

4.Vegh and Vuletin (2012) (PDF) ![]() also find evidence that about 35 percent of the developing countries have shifted from procyclical to countercyclical monetary policy over the past decade. Return to text

also find evidence that about 35 percent of the developing countries have shifted from procyclical to countercyclical monetary policy over the past decade. Return to text

Please cite as:

Coulibaly, Brahima (2013). "The Long Road to Countercyclical Monetary Policy in Emerging Market Economies," IFDP Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 03, 2013. https://doi.org/10.17016/2573-2129.02

Disclaimer: IFDP Notes are articles in which Board economists offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than IFDP Working Papers.