FEDS Notes

February 03, 2020

How Global Value Chains Change the Trade-Currency Relationship

François de Soyres, Erik Frohm, Vanessa Gunnella1

Economics textbooks outline a clear-cut relationship between movements in a country's exchange rate and its export volumes, the exchange rate elasticity of exports. When a currency depreciates, export volumes are expected to increase by some amount due to competitiveness gains in export markets. Yet, some recent episodes of significant exchange rate movements, such as those in Japan (2012-2014) and the UK (2007-2009), were not associated with very large movements in trade volumes (Leigh et al. 2017). This perceived unresponsiveness of exports to exchange rate movements has raised the question as to whether the exchange rate elasticity of export volumes has changed, or even become zero.

With the rise of Global Value Chains (GVCs), firms increasingly (i) use imports to produce exports and (ii) export inputs that are re-exported further by their trading partners. An example of the first is a car manufacturer in Mexico that exports finished products to the United States. The car manufacturer imports parts and components from the United States – for example the gear box or the microchips that connect the car to the internet – to produce the exported car. As an example of the second, a Mexican manufacturer can export inputs (e.g. suspensions or directional systems) to a firm in Canada that assembles a finished car for exports and final consumption in the United States. Alternatively, the domestic value-added embedded in the Mexican exports to Canada can also be returned to Mexico for final consumption (as re-imported exports). With such complex linkages in the production process of exporters, the consequences of a currency depreciation for export volumes depend on the details of both upstream and downstream interconnections with other countries.

Recent research suggests that global value chains (GVCs), and more generally the development of international production networks, could be an important part of the reason why the exchange rate elasticity of exports may have fallen. In de Soyres et al. (2018), we use inter-countries input-output tables to build relevant GVC participation indices taking into account both upstream and downstream linkages. These indices shed a new light on the effectiveness of depreciation. This note summarizes the main results of that paper, drawing out the most policy-relevant implications. Our main findings are that the consequences of currency depreciations on exports depend not only on where all imported inputs come from (as discussed previously in the literature), but also on what is the ultimate destination of final consumption. In some cases, depreciations can even hurt export volumes.

The literature

So far, the literature studying the impact of GVCs on export elasticities focused on the role of imported content of exports, arguing that a greater share of imported inputs in exports imply that any export price competitiveness gained by currency depreciation will be partly offset by increasing costs of imported inputs. Ahmed et al. (2015) show that GVC participation lowers the elasticity of manufacturing exports to the real effective exchange rate (REER) by 22% on average and by close to 30% for countries with highest GVC participation. Arbatli and Hong (2016) as well as Shousha (2019) find that high participation in global production chains is an important determinant of export elasticities.

Moreover, other factors that could reduce the responsiveness of exports to exchange rate movements relate to the increasing use of pricing-to-market strategies among large exporters that tend to keep their export prices stable and absorb any variability in the exchange rate in their markups. Amiti et al. (2014) finds that import intensity and market share are key determinants of exchange rate pass-through.2

New results

In a recent paper (de Soyres et al. 2018), we use sectoral data for 40 countries and 33 sectors between 1995 and 2009 and apply recent advances in the value-added decomposition of trade flows to pin down three distinct mechanisms through which GVCs impact exchange rate elasticities.

- First, we find that an increase in the export's share of foreign value-added from a country with a different currency (the 'FV index', for 'Foreign Value Added') reduces the change in export price in response to exchange rate movements, hence lessening the associated change in export volumes. This is a standard and previously studied channel by which potential gains from depreciations are offset by an increase in the price of imported inputs. Note that this channel is not operative when foreign inputs come from a country with the same currency because in such a case a depreciation has no impact on import prices, a caveat our paper takes into account when constructing the indices.

- Second, we show that a greater share of exports that return as imports in a country sharing the same currency (the 'RDV index', for 'Return Domestic Value Added') weakens the exchange rate responsiveness of export volumes. In other words, goods that are reimported back are less responsive to currency depreciation. Indeed, when an exported product is re-imported back, the relative price gains associated with a depreciation when exporting are offset by an equal loss when re-importing it. Intuitively, doing a trade "back-and-forth" cancels out the potential benefits associated with a depreciation. Put differently: if the final demand driving exports is located at home, a depreciation has little impact on trade flows.

- Third, an increase in the share of exports used in the destination country to produce further re-exports which are ultimately consumed in a third country (the 'IV index', for 'Intermediated Value Added') increases the responsiveness of trade flows to the direct trading partner's nominal effective exchange rate, creating significant inter-dependencies across economies. For example, consider a good that is exported from China to Europe and subsequently from Europe to the United States. In this case, a depreciation of the euro vis-à-vis the US dollar would boost exports from Europe to the US and consequently also propel exports from China to Europe. This mechanism underlines the high degree of international interconnection that characterizes today's production processes: exports are not only affected by the value of one's own currency, but also by the value of one's trade partner's currency vis-à-vis third countries.

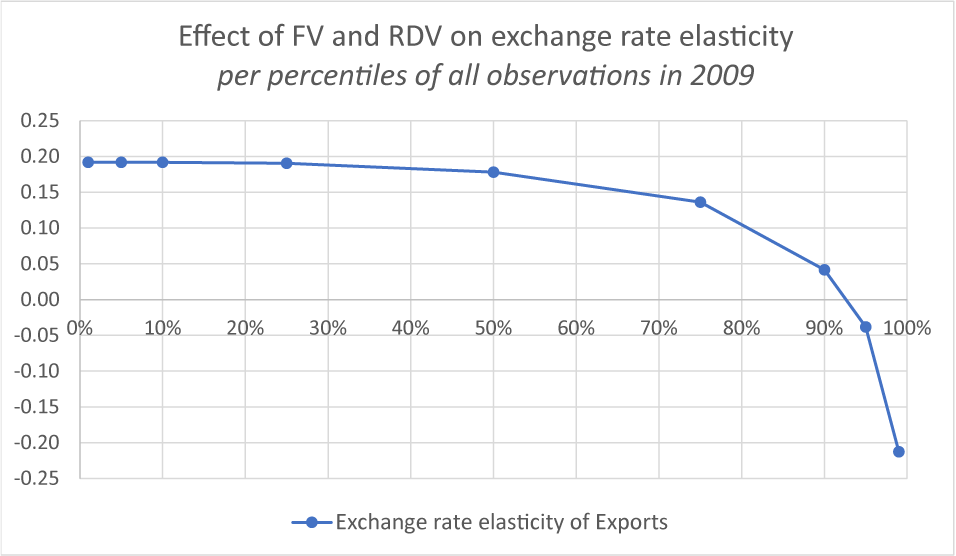

Our analysis implies that the sensitivity to currency depreciation will be different for each sector and origin-destination pairs, depending on both upstream and downstream participation in GVCs. To illustrate our results, figure 1 ranks all observations according to the sum of their FV and RDV indices, and plots the corresponding exchange rate elasticity. The downward sloping line shows that higher participation in international production networks lowers the exchange rate elasticity of exports. Interestingly, it also shows it is possible for a currency depreciation to actually reduce a sector's exports to a specific destination as evidenced by the negative values for very high values of GVC indices. As a polar case, imagine a sector that sources a significant share of its input from a country with a different currency, sells its good abroad, and re-imports it back for domestic consumption. In such a case, due to the foreign value-added in exports, a depreciation would increase the production price in domestic currency. Moreover, since final demand originates from home, consumers simply see an increase in the final price and hence lowers their consumption. The fact that the good was exported and then re-imported means that the lower domestic consumption will translate into a decrease in the country's exports. Such a negative effect of exchange rate depreciation on export volumes underlines the importance of using precise input-output data when forecasting the effect of currency changes.

Figure 1: Elasticity of export volumes to exchange rates for different quantiles of FV and RDV indices

Note: The horizontal axis corresponds to the different quantiles of GVC participation according to the weighted sum of FV and RDV indices, with weights corresponding to the marginal impact of the indices on export elasticities as measured in de Soyres et al (2018). The curve plots the corresponding elasticity of export volumes to exchange rates. For sectors with the highest level of both FV and RDV (at the far right of the graph), the corresponding elasticity is negative, meaning that a devaluation would decrease exports.

Source: de Soyres et al. (2018).

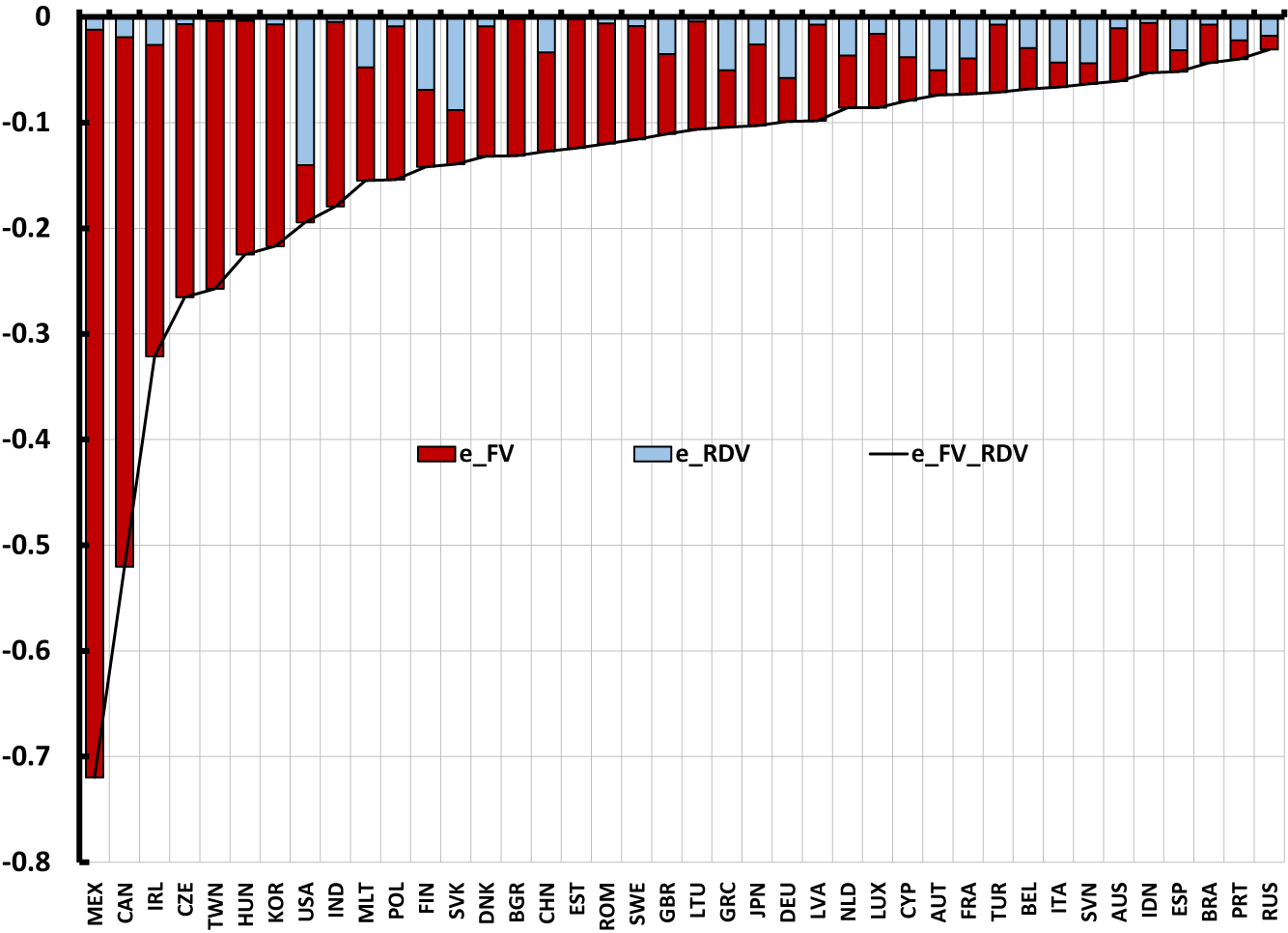

Moreover, our findings also have country-level consequences. Aggregating all sectors in each country, figure 2 shows the total impact from FV and RDV for all countries in the sample (on the x-axis). The figure plots the reduction in exchange rate elasticity coming from each index, with the red part representing the changes due to FV while the blue part represents the change due to RDV. As we see in the figure, the elasticities among economies in the Economic Monetary Union (EMU) in Europe are heavily impacted by back-and-forth trade (RDV), which account for a large proportion of the dampening impact of global value chains. This tells us that both types of GVC relations are important elements in muting the response of exports to movements in the exchange rate. For large currency areas like the euro area or large domestic markets like the United States, back-and-forth trade is even more important in affecting the elasticities. In contrast for small open economies, the lower trade elasticities are primarily driven by upstream linkages (FV).

Note: The figure reports the total impact from FV and RDV on the exchange rate elasticity of exports of a given country across the origin-sector-destination dimension (on the vertical axis). Elasticities are computed from the specification in column (4) of Table 3 in de Soyres et al. (2018), including origin-sector-destination fixed effects and time dummies.

Source: de Soyres et al (2018), based on World Input-Output tables (2013 release) and BIS data.

Policy implications

To understand the consequences of exchange rate movements for export volumes is key for policymakers. As shown in this Note, international production linkages may alter the exchange rate elasticities, and in some cases, even reverse their sign. Utilizing indices of global value chain participation, based on currencies rather than countries, illuminates the origin of imported inputs and the country of final consumption for exports and their respective impact on the export elasticities. For example, for countries developing a regional value chain, several forces are at play: sourcing inputs form a country with the same currency has no impact on the relationship between exports and the exchange rate, but exports returning to a country with the same currency decreases the elasticity. Hence, future developments in international linkages might have different impact on different countries depending on the joint evolution of both global value chain participation and common currency areas.

References

Ahmed, A, M A Appendino, and M Ruta (2015), "Depreciations without exports? Global value chains and the exchange rate elasticity of exports", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7390

Arbatli, E and H H Hong (2016), "Singapore's Export Elasticities: A Disaggregated Look into the Role of Global Value Chains and Economic Complexity", IMF Working paper WP/16/52

Amiti, M, O Itskhoki, and J Konings (2014), "Importers, exporters, and exchange rate disconnect", American Economic Review 104(7): 1942-78.

Boehm, C, A Flaaen, and N Pandalai-Nayar (2018), "Input Linkages and the Transmission of Shocks: Firm-Level Evidence from the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake", Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Boz, E, G Gopinath, and M Plagborg-Møller (2017), "Global trade and the dollar" NBER Working Paper w23988.

Demian, C-V and F di Mauro (2017) "The exchange rate, asymmetric shocks and asymmetric distributions", International Economics.

de Soyres, F, E Frohm, V Gunnella and E Pavlova (2018), "Bought, Sold and Bought Again: Complex value chains and export elasticities", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 8535.

de Soyres, F. and Gaillard, A. (2019a). "Value added and productivity linkages across countries". FRB International Finance Discussion Paper No.1266.

Imbs, J, and I Mejean. (2017), "Trade elasticities", Review of International Economics 25(2): 383-402.

Johnson, R C, and G Noguera (2017) "A Portrait of Trade in Value-Added over Four Decades", Review of Economics and Statistics 99(5): 896-911.

Leigh, D, W Lian, M Poplawski-Ribeiro, R Szymanski, V Tsyrennikov and H Yang (2017), "Exchange rates and trade flows: disconnected?", IMF Working Paper, WP1758.

Shousha, Samer (2019). "The Dollar and Emerging Market Economies: Financial Vulnerabilities Meet the International Trade System". International Finance Discussion Papers 1258.

Timmer, M. P., Dietzenbacher, E., Los, B., Stehrer, R. and de Vries, G. J. (2015), "An Illustrated User Guide to the World Input–Output Database: the Case of Global Automotive Production", Review of International Economics., 23: 575–605

1. François de Soyres ([email protected]) is an Economist in the Division of International Finance of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Erik Frohm is a Senior Economist at the Sveriges Riskbak. Vanessa Gunnella is an Economist at the European Central Bank. The views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. Recent research has also acknowledged that the dominant role of invoicing in US-dollars in international trade might increase the exchange rate elasticity of any country to the US-dollar. See Boz et al. 2017. Return to text

de Soyres, François, Erik Frohm, and Vanessa Gunnella (2020). "How Global Value Chains Change the Trade-Currency Relationship," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 6, 2020, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2504.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.