FEDS Notes

September 26, 2013

Looking for Shortages of Skilled Labor in the Manufacturing Sector

Jessica Stahl and Norman Morin

Anecdotal reports have suggested that some firms have struggled to find sufficient numbers of skilled workers. For instance, the Federal Reserve's January 2013 Beige Book (PDF) mentioned that "contacts in several [Federal Reserve] Districts reported difficulties finding qualified workers in some specialized fields, such as skilled manufacturing, energy, and IT" (page ix). Here we focus on the manufacturing sector. Although manufacturing currently accounts for only 10½ percent of private employment, the reports of labor shortages are often specific to this sector.1 Indeed, earlier this year, inquiries conducted by the Philadelphia ![]() and New York

and New York ![]() Federal Reserve Banks suggested that skilled labor shortages were a significant factor restraining hiring in the manufacturing sector--though slow expected growth of sales was by far the most important reason cited.2

Federal Reserve Banks suggested that skilled labor shortages were a significant factor restraining hiring in the manufacturing sector--though slow expected growth of sales was by far the most important reason cited.2

Further information about the extent of skilled labor shortages in manufacturing--and, importantly, how they have changed over time--can be seen in data from the Census Bureau's Quarterly Survey of Plant Capacity Utilization (QPC) and its annual predecessor, the Survey of Plant Capacity (SPC). The QPC, which is jointly funded by the Federal Reserve Board and the Department of Defense, provides the data used to benchmark the Federal Reserve Board's measures of manufacturing capacity. The survey asks roughly 7,500 plant managers about their plants' actual production and total sustainable productive capacities and, when applicable, the reasons that plants are operating below capacity levels of output.

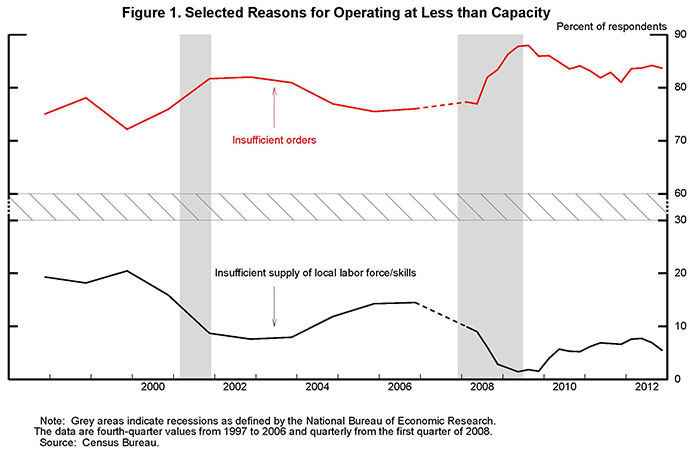

The QPC and SPC have indicated fairly widespread labor shortages before. As shown in figures 1 and 2, "Insufficient supply of local labor force/skills" was cited as a factor restraining production by more than 20 percent of survey respondents in the late 1990s and by nearly 15 percent during the expansionary period leading up to the most recent recession.3

| Figure 2 |

|---|

| Year | Percent of Respondents |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 20.4 |

| 2002 | 7.6 |

| 2006 | 14.5 |

| 2009 | 1.5 |

| 2012 | 5.4 |

|

|

The share of plant managers choosing this reason plummeted to less than 2 percent during the recession. The share reporting that skills shortages were a restraint on production has moved up somewhat since then: As of the fourth quarter of last year, the proportion was about 5-1/2 percent (with a standard error of 0.7 percentage point), somewhat below the 7-3/4 percent share it reached in the second quarter of last year. The share citing skill shortages remains below its historical average, and the share is not higher than one would expect given the state of the wider labor market and the amount of slack in the manufacturing sector. In particular, the share is broadly consistent with a regression-based prediction using the unemployment rate and manufacturing capacity utilization. Indeed, both historically and currently, the dominant reason cited by plant managers for operating at less than capacity has been "Insufficient orders" (the red line in the figure); this reason was chosen by nearly 84 percent of respondents at the end of last year (with a standard error of 1.1 percentage points) and remains above its long-run average.4

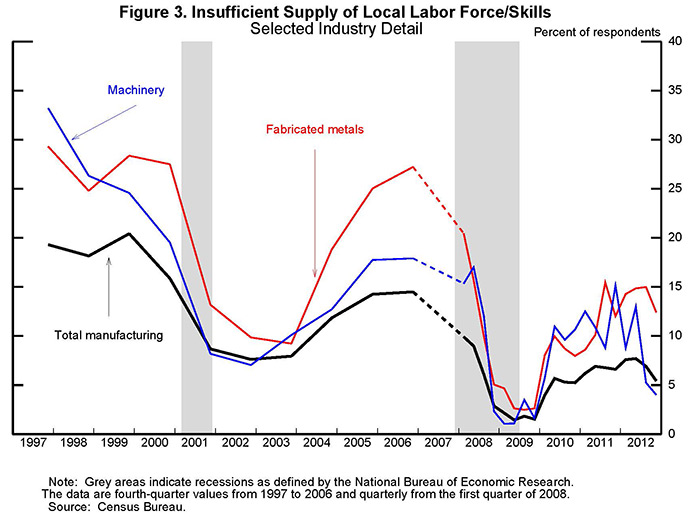

Even when the QPC and SPC data are examined for major industry categories within the broader manufacturing sector, they suggest that skilled labor shortages were not a major factor restraining production in the fourth quarter of 2012 (the latest available data). Figure 3 presents results for two industries that are frequently mentioned in press reports as facing labor shortages: machinery and fabricated metals. Plant managers in these industries historically have been significantly more likely than other managers to report that skilled labor shortages are restraining production: For example, they were mentioned in the late 1990s by one-third of respondents in the machinery industry. However, even for these two industries, the share of survey respondents in recent quarters who cited skilled labor shortages as a reason for operating below capacity has remained well below the share before the recession.

All told, while some skilled labor shortages are being reported in the manufacturing sector, the extent to which these shortages are restraining production appear about in line with the current sluggishness in the labor market and the degree of slack in the manufacturing sector. Furthermore, the finding that skilled labor shortages are not a significant and widespread restraint on production is consistent with other data continuing to show subdued increases in the wages and salaries of manufacturing workers.

1. For instance, the 2011 skills gap report, Boiling Point? The Skills Gap in U.S. Manufacturing ![]() , sponsored by The Manufacturing Institute (an affiliate of the National Association of Manufacturers) and Deloitte, stated that skilled labor shortages were a pressing problem within manufacturing, but noted that "[t]his problem is not new" (p. 1). Return to text

, sponsored by The Manufacturing Institute (an affiliate of the National Association of Manufacturers) and Deloitte, stated that skilled labor shortages were a pressing problem within manufacturing, but noted that "[t]his problem is not new" (p. 1). Return to text

2. "Cannot find workers with required skills" was the fourth most frequently named factor in the case of New York (where 33 percent of respondents named it among the three most important restraints on hiring) and fifth in the case of Philadelphia (around 25 percent). These figures are lower than in similar inquiries conducted in mid-2012; unfortunately, comparisons are not available for periods before the most recent recession, when the labor market was tighter. Return to text

3. The responses are weighted by plant-level receipts; unweighted results are similar. Return to text

4. In addition to "Insufficient orders" and "Insufficient supply of local labor force/skills," the other choices are: "Not most profitable to operate at capacity," "Sufficient inventory of finished goods on hand," "Insufficient supply of materials," "Equipment limitations," "Seasonal operations," "Lack of sufficient fuel or electrical energy," "Storage limitations," "Logistics/transportation constraints," "Strike or work stoppage," and "Environmental restrictions." Respondents may choose as many factors as they deem applicable. Return to text

Please cite as:

Stahl, Jessica C., and Norman Morin (2013). "Looking for Shortages of Skilled Labor in the Manufacturing Sector," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 26, 2013. https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.0001

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board economists offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers.