FEDS Notes

October 1, 2015

Why Boomerang? Debt, Access to Credit, and Parental Co-residence among Young Adults

Lisa J. Dettling and Joanne W. Hsu

A persistent media narrative from the Great Recession is the phenomenon of "boomerang" kids, that is, the rapid increase of young adults moving back in with their baby boomer parents. From a life-cycle perspective, boomerang kids may be delaying wealth-building, and they may be a strain on parental resources. From a macroeconomic perspective, increased rates of parental co-residence have important implications for the economy at large. Young adults who co-reside with parents spend less on rent, furniture, and other expenses associated with living independently, which can depress aggregate consumer spending and economic growth. In this note, we describe our research examining the relationship between debt, access to affordable credit and parental co-residence decisions among young adults.1 We find that the rise in debt-holding between 2005 and 2013--driven primarily by a rise in student loan debt--can explain 32 percent of the increase in flows into parental co-residence, and 26 percent of the increase in median time spent in co-residence.

Trends in Parental Co-residence

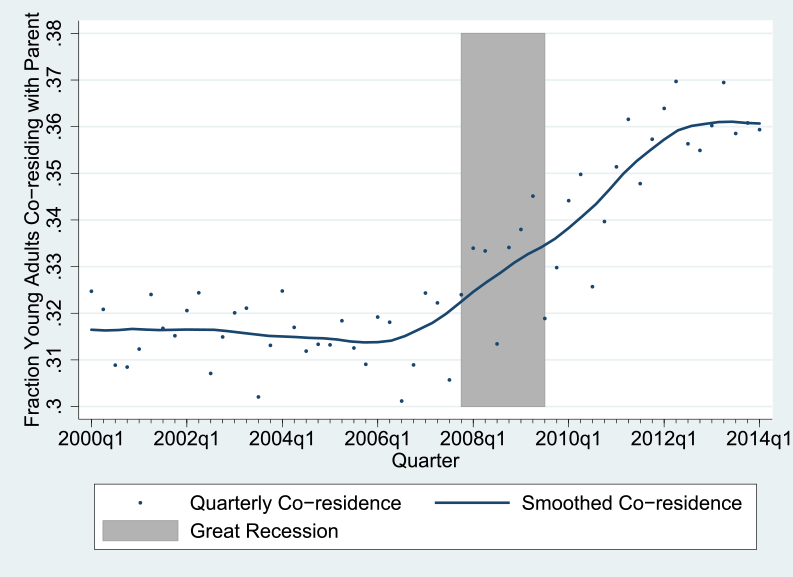

Figure 1 displays quarterly and smoothed trends in parental co-residence among adults age 18 to 31 from 2000 to 2014, calculated from the Current Population Survey (CPS). As seen on the solid line, which abstracts from seasonal variation due to school enrollment periods, the fraction of young adults co-residing with a parent was fairly stable from 2000 to 2006, when about 32 percent of young adults co-resided with a parent. Then, the fraction of young adults living with their parents then began to grow steadily, reaching a historic high of approximately 36 percent in 2014. Despite media narratives suggesting this phenomenon is a product of the Great Recession, the increase in the parental co-residence rates began well before onset of the Great Recession, and has not abated during the recovery.2

| Figure 1: Parental Co-residence Among Young Adults Grew Markedly From 2005 to 2014 |

|---|

|

Source: Dettling and Hsu (2014).

The Relationship between Debt and Parental Co-residence

We propose that the rise in parental co-residence during the Great Recession in the United States can be partially explained by increases in borrowing constraints among young adults, stemming from increases in debt holding.

In standard economic life-cycle models, young adults typically prefer to consume more than their current income permits, since they are generally on the steep part of the age-earnings profile. Borrowing enables young adults to smooth consumption over time by shifting resources from higher-earning periods in the future. However, consumers with high debt-to-income ratios or poor credit records typically face higher costs of borrowing and limited access to additional credit. Parental co-residence, which can substantially reduce current period expenses by reducing or eliminating housing payments, could be another way to smooth consumption when a young adult has exhausted his ability or willingness to borrow.3 If parental co-residence is used in this manner, then young adults who are more indebted and of higher credit risk will differentially opt into parental co-residence.

To examine the relationship between debt, access to credit and parental co-residence decisions, we employ a quarterly panel of credit reports derived from the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax. The data includes information on debt balances, credit risk scores, and the composition of their household, which permits us to examine how debt and credit risk affect the propensity for an individual to move into, or out of parental co-residence.4

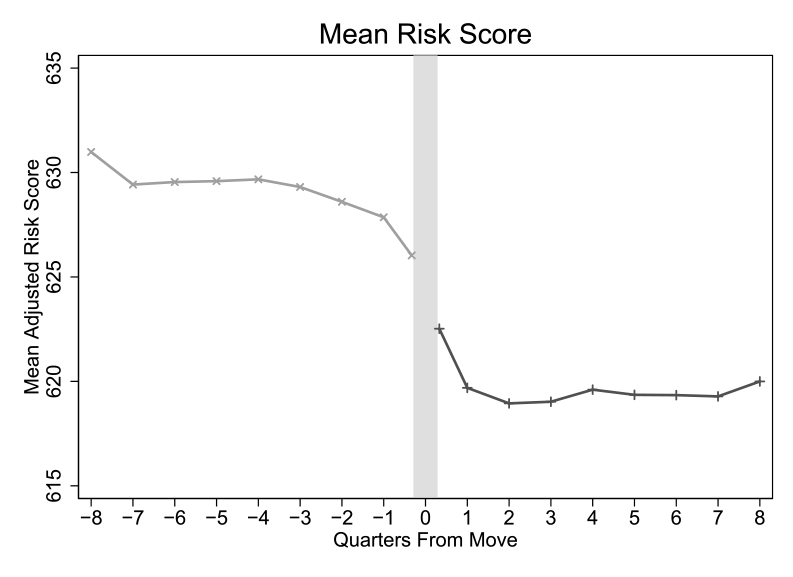

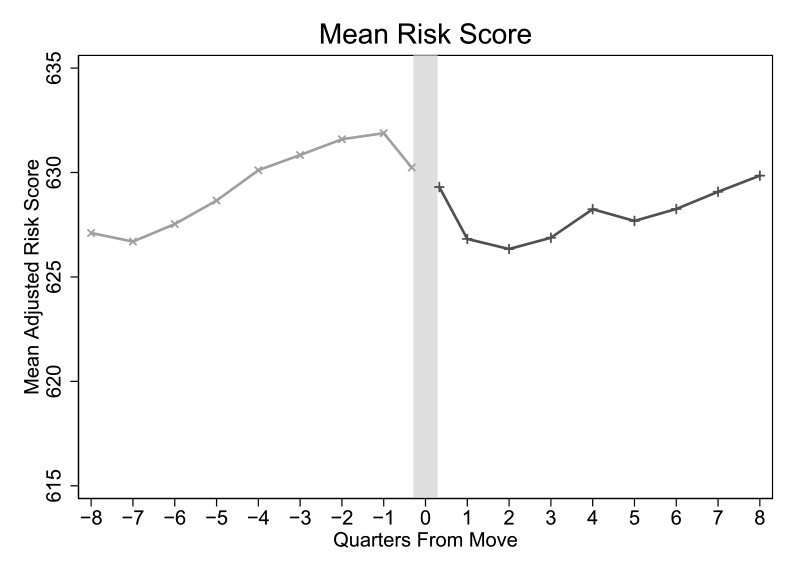

We hypothesize that young adults who face higher costs of credit will differentially opt to co-reside with parents because they are unable to obtain affordable credit in order to smooth consumption. As a first pass, we examine how credit risk evolves for young adults who ultimately move into co-residence and those that do not. If our hypothesis is correct, we would expect to observe the average individual who moves into co-residence to have lower or declining credit scores relative to those who do not. Figure 2 plots the time path of credit scores for individuals who made the transition from living on their own to living with a parent in 2(a) and, as a comparison, individuals who moved, but continued to live on their own in 2(b).5 As seen in figure 2(a), mean credit scores fall from 632 to 626 in the quarters leading up to the move, and after the move, credit scores stabilize. For individuals who move but continue to live on their own (figure 2(b)), mean credit scores rise before the move and continue to rise after the move. The different patterns for the two types of moves suggest credit risk and borrowing costs may indeed help to explain co-residence choices.

| Figure 2(a): Credit Risk Typically Rises Before Moves into Parental Co-residence, but not Before Other Types of Moves; Mean Credit Risk Score Before and After Moves into Parental Coresidence |

|---|

|

Source: Dettling and Hsu (2014).

| Figure 2(b): Credit Risk Typically Rises Before Moves into Parental Co-residence, but not Before Other Types of Moves; Mean Credit Risk Score Before and After Other Types of Moves |

|---|

|

Source: Dettling and Hsu (2014).

To more formally investigate the descriptive relationship found in figure 2, we estimate a series of ordinary least squares regressions which relate debt-holding and credit risk in quarter t to the propensity to enter and exit co-residence between quarter t and t+1, controlling for individual characteristics, county and year fixed effects and county-level unemployment rates and home prices.

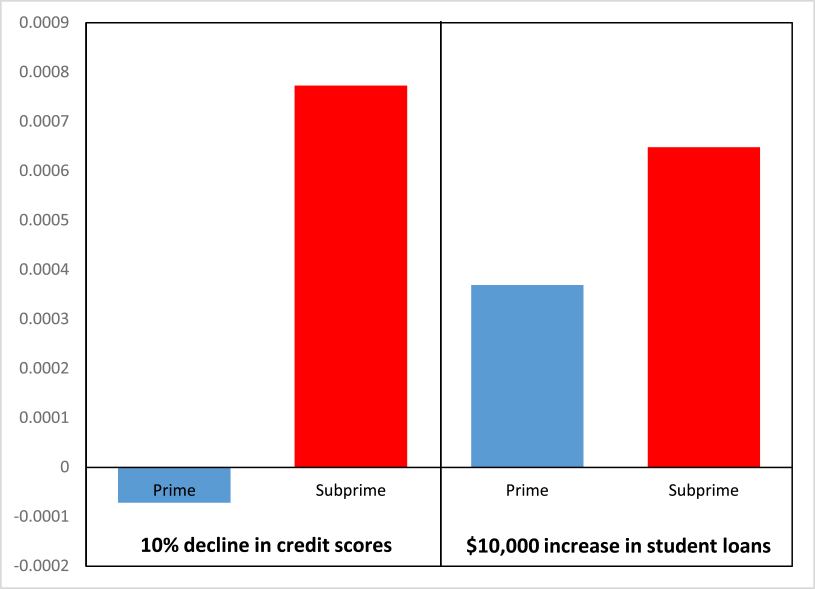

Figure 3 displays coefficient estimates of the effect of credit risk and debt on entry into co-residence, separately for prime and subprime borrowers. We focus on this distinction prime borrowers are typically able to access more credit and at better terms. As seen in the red bars in figure 3, our results indicate that declining credit scores and higher student loan balances are associated with statistically significant and economically meaningful increases in the likelihood a subprime borrower will move into parental co-residence in the following period. Evaluated at the mean rate of moves into parental co-residence, these estimates imply that among subprime borrowers, a 10 percent decline in credit scores, or a $10,000 increase in student loans, increases transitions into parental co-residence by 8.1 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively. Consistent with the hypothesis that young adults facing higher borrowing costs will be more likely to enter parental co-residence, the blue bars in figure 3 indicate that we find relatively smaller effects of debt on entry into co-residence for prime borrowers. We also estimate the effects of debt on durations spent in co-residence after moving in and find similar effects of credit risk.

| Figure 3: Effects of Declining Credit Scores and Larger Student Loans on Parental Co-residence Are Larger for Borrowers Facing Higher Costs of Credit (Coefficient Estimates) |

|---|

|

Source: Dettling and Hsu (2014).

In order to establish a causal relationship between borrowing constraints and parental co-residence we also estimate models that exploit plausibly exogenous reductions in credit card limits. After the financial crisis, card issuing banks sought to mitigate portfolio exposure by reducing consumer credit lines. Card issuer regulations associated with the Credit CARD Act led to a spike in credit line reductions for a broad swath of consumers between the announcement of the new regulations in 2007 and their implementation in 2010. We show that these credit limit cuts were done with no regard to consumers' credit risk or payment behavior, thus, providing a unique natural experiment for the effect of credit access on co-residence choices for the subsample of young adults with credit cards. We find qualitatively similar results to our main analyses: declines in access to credit increase parental co-residence.

What Can Explain the Recent Increase in Parental Co-residence?

We have demonstrated that, at the individual-level, debt, credit and borrowing costs are associated with increased propensities to transition into parental co-residence. This raises the question, can this explain the aggregate increase in co-residence observed over this period?

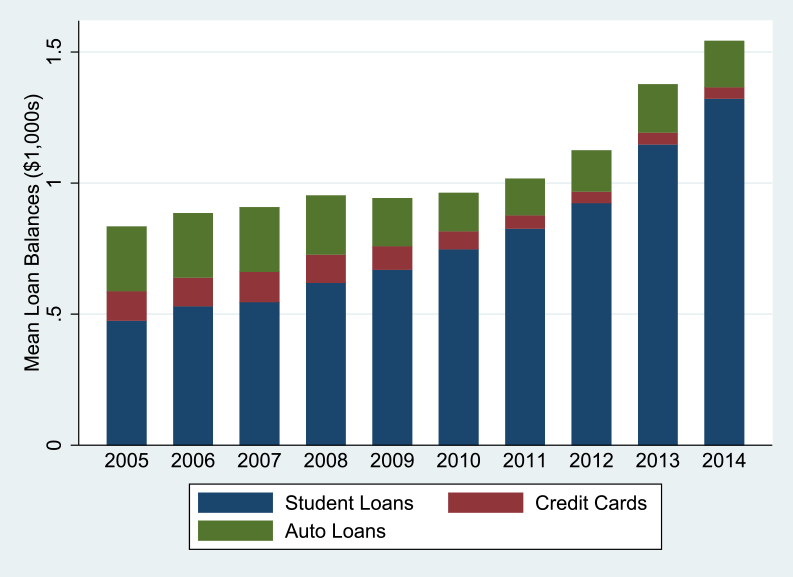

Between 2005 and 2013, debt holding among young adults rose substantially. Figure 4 plots mean loan balances for young adults aged 22 over time, separately for student loans, credit cards, and auto loans in our data. Total loan balances rose over this period, and were increasingly dominated by student loans. This trend implies that recent cohorts of young adults interact with markets for credit cards, auto loans, and mortgages while holding much more debt in the form of student loans than previous cohorts of young adults. Moreover, recent industry research indicates that the credit risk of student loan debtors has differentially increased since 2005 (FICO 2013). This change in credit risk, coupled with the increase in student loan borrowing, implies that on aggregate, young adults have likely faced higher costs of borrowing and have become increasingly credit constrained over this period.6

| Figure 4: Debt-Holding at Age 22 Rose from 2005 to 2014, Mostly Due to a Rise in Student Loan Debt |

|---|

|

Source: Dettling and Hsu (2014).

Using estimates from our regression models, we can estimate the impact of debt holding on aggregate flows into and out of co-residence between 2005 and 2013. We find that the rise in debt-holding between 2005 and 2013 can explain 32 percent of the increase in flows into parental co-residence, and 26 percent of the increase in median time spent in co-residence.

While we have demonstrated that debt, and particularly the rise in student loan debt, can explain a substantial portion of the recent increase in parental co-residence, an important question remains as to what else may explain elevated rates of parental co-residence during the Great Recession. While anecdotal evidence suggests this phenomenon is a product of weak labor markets, figure 1 indicates that co-residence rates began to rise before the onset of the Great Recession, and remain elevated despite improvements in the labor market. While analyses have found that own unemployment does predict individual living arrangements (Lee and Painter 2013; Paciorek 2015), fluctuations in aggregate unemployment are unable to explain recent trends (Hoynes and Bitler 2015).7 Based on our estimates, the decline in home prices in the Great Recession should have encouraged independent living. While outside the scope of our analysis, it is possible that non-economic factors, such as cultural changes across cohorts, could also play a role.8

References

Bitler, Marianne, and Hilary Hoynes. 2015. "Living Arrangements, Doubling Up, and the Great Recession: Was This Time Different?" American Economic Review, 105(5): 166-70.

Dettling, Lisa and Joanne Hsu (2014) "Returning to the Nest: Debt and Parental Co-residence Among Young Adults" Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2014-80, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

FICO (2013, January). "Is growing student loan debt impacting credit risk?" Insights White Paper Series No. 65, Fair Isaac Corporation.

Hochwald, L. (2013). "Tough love: Should boomerang kids pay rent to their parents." Forbes October 17, 2013.

Howe, Neil and William Strauss (2000) Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation Vintage Books, New York.

Lee, K. O. and G. Painter (2013). "What happens to household formation in a recession?" Journal of Urban Economics 76, 93-109.

Paciorek, A. (2015). "The long and short of household formation." Real Estate Economics.

Parker, K. (2012). "The boomerang generation." PEW Research Center Social and Demographic Trends Project.

1. This note describes the findings of a more detailed companion piece: "Returning to the Nest: Debt and Parental Co-residence Among Young Adults (PDF)" FEDS Working Paper 2014-80. Return to text

2. Dates of the Great Recession displayed were determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Return to text

3. Young adults in the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances typically spend between 30 and 50 percent of their income on rent: those living with spouse or partner spend 30 percent, those living with roommates spend 48 percent, and those living alone spend 46 percent of their income on rent. The survey does not ask about rental payments made by young adults in parental co-residence. However, a Pew research study found that only 32 percent of young adults aged 18 to 31 in parental co-residence pay any rent to their parents (Parker, 2012). Moreover, anecdotal evidence also suggests young adults who do pay rent typically pay far less than market value; for example, a recent media article geared at parents of children in co-residence recommends parents charge below-market rent not exceeding 10 percent of the adult child's take-home pay (Hochwald, 2013). Return to text

4. While household interrelationships are not available in the data, we are able to infer parental co-residence from age differences between household members. See Dettling and Hsu (2014) for more details. Return to text

5. Note that we expect the general moves in figure 2(b) to be a combination of individuals upgrading residences, those moving to enter different living arrangements, as well as those downgrading residences for the same cost-saving reasons one might move in with parents. Therefore, the analysis in figure 2(b) is not exactly a counterfactual to the transition into parental co-residence in 2(a), but the comparison can still be informative. Note that the slight decline in credit scores in in the quarters immediately surrounding the move seen in figure 2(b) likely reflects additional expenses and credit inquiries associated with moving. In both figures 2(a) and 2(b) the sample before/after a move is limited to individuals who move exactly once and are observed eight quarters before or after the move. Therefore, the sample used to calculate the means to the left of zero is not the same as the sample used to calculate the means to the right of zero. Since individuals must naturally age over the eight quarters during which they are observed up until or after a move, and age and year may have its own separate effects on credit scores, we plot age- and quarter-adjusted scores. These adjusted scores were calculated from the residuals of a regression relating credit scores to age and quarter fixed effects. They were calculated using the entire sample, not the limited sample used for the construction of this figure. Return to text

6. The constraints induced by leaving school with more debt than previous cohorts are separate from any constraints induced by the Credit CARD Act of 2009, which specifically prevented consumers under age 21 from acquiring credit cards without proof of income. Return to text

7. Lee and Painter (2013) use panel data from 1975-2009 and find own unemployment reduces the propensity for an individual to leave parental homes. Similarly, Paciorek (2015) uses cross-sectional data from 2006-2009 and finds own unemployment increases young adults propensities to live with family members. Hoynes and Bitler (2015) use state-level panel data over business cycles spanning from 1980 to 2013, and find a small, negative, and statistically insignificant relationship between state-level unemployment rates and the propensity for young adults to live independently. Return to text

8. For example, Howe and Strauss (2000) note that in a 1973 survey only 33 percent of young adults responded that it was a good idea for older people to live with their grown children. By 1994, that number had risen to 55 percent (p. 132). The authors also provide numerous examples of survey evidence suggesting that Millennials have more positive attitudes towards their parents, are closer to their parents, and have more similar tastes to their parents compared to young adults from earlier cohorts (pp. 185-188). Return to text

Please cite as:

Dettling, Lisa J., and Joanne W. Hsu (2015). "Why Boomerang? Debt, Access to Credit, and Parental Co-residence among Young Adults," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 01, 2015. https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.1621

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board economists offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers.