FEDS Notes

February 13, 2026

Measuring Cross-Border Securities Positions: Explaining Asymmetries between U.S. Treasury TIC and IMF PIP (formerly CPIS) Data

Ruth Judson and Nyssa Kim1

Introduction

Understanding the effects of cross-border securities holdings depends critically on accurate data, and two significant data sources in this area are the U.S. Treasury's Treasury International Capital (TIC) system and the IMF's Portfolio Investment Positions by Counterpart Economy (PIP, formerly known as CPIS).2 In this note, we compare TIC-reported U.S. securities liabilities (that is, U.S. securities held by foreign residents) with the "mirror" of PIP-reported securities assets where the U.S. is the counterparty (that is, U.S.-issued securities held by each country's residents).

In principle, these datasets should mirror one another: country A's portfolio liabilities to other countries should equal these other countries' portfolio holdings of country A's assets. However, in practice, there are distortions in the data for various reasons, including data collection methodology and limitations on both the scope of data collection and data release, the handling of reporting by large securities depositories and custodians, and the presence of offshore investment funds. These distortions and limitations generate discrepancies between the TIC and PIP which are important for researchers to understand. We present three types of comparisons of TIC and PIP: in aggregate, broken down by official and private holdings, and by country. We review the factors that contribute to these differences, explain what some of the differences show, and provide advice to researchers.

Aggregate Data and Overview of Key Differences between TIC and PIP

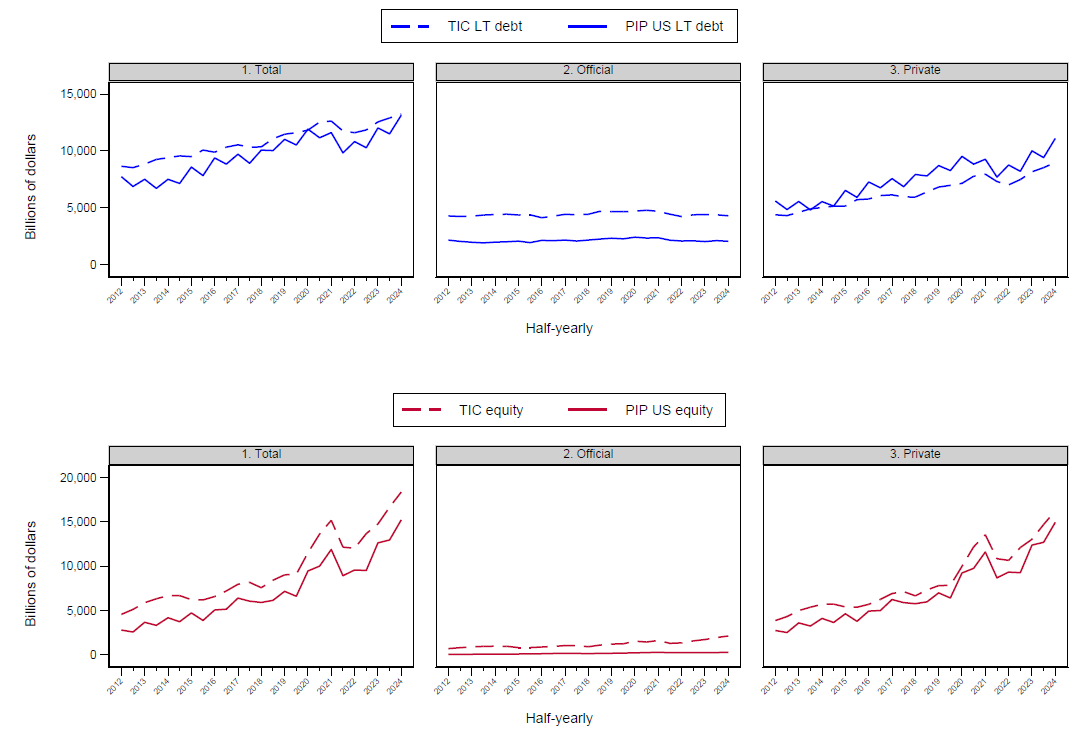

In aggregate, foreign holdings of U.S. long-term securities reported in TIC generally exceed the mirror assets reported in PIP. Figure 1 shows TIC and PIP reporting of foreign holdings of long-term U.S. debt (blue lines) and equity (red lines) from 2012 to 2024.3 The two rows show long-term debt and equity. The columns from left to right show total, official, and private holdings. Total holdings, the left column, are higher than those reported in PIP, but the movements over time are generally similar, with the main difference a slight annual "sawtooth" pattern in the PIP data.

Source: U.S. Treasury, TIC.

This phenomenon of self-reported liabilities' exceeding the corresponding claims reported by other investing countries is not unique to the United States, and indeed, the IMF Task Team on Global Asymmetries (TT-GA), which focuses on asymmetries in key areas of external sector statistics, is exploring the global reporting pattern that total reported cross-border liabilities exceed the corresponding cross-border claims—or assets—from the issuer side.4 The U.S. role in portfolio investment markets is substantial, and the asymmetry between PIP and TIC is a significant portion of the global discrepancy. Thus, examining and understanding the causes of the differences between U.S. TIC and PIP reporting can illustrate the asymmetries seen elsewhere. The differences seen in Figure 1 flow from three significant differences between PIP and TIC: country coverage, the scope of the private and official sectors, and country attribution.

Country coverage

First, PIP collects data on a voluntary basis from a limited—albeit very large—set of countries, about 90 as of late 2024. Fortunately, these countries include nearly all of the largest economies and securities holders and issuers. Most notably, PIP does not include reporting from Taiwan and the British Virgin Islands. PIP collections occur twice yearly, for data as of end-June and end-December, but some countries report only in December, and as a result, values for June are typically a bit below the corresponding year's December values, generating the somewhat jagged patterns in some of the panels of Figure 1. In contrast, TIC's data collection is legally required and comes from U.S.-based custodians, issuers, and investors.

Scope of official and private sectors

TIC collects data separately for official and private investors but PIP collects data only for private holdings. However, the scope of private holdings differs across the two datasets. PIP's reporting includes all holdings except for foreign exchange reserves, which are collected in the IMF's companion to PIP, SEFER. In contrast, TIC's definition of "official" extends beyond foreign exchange reserves to include all holdings by government or government-operated entities, including sovereign wealth fund holdings and government-owned or government-managed banks.5 Table 1 summarizes the TIC and PIP / SEFER classifications of official and private holdings.

Table 1: TIC and PIP/SEFER Reporting by Sector

| TIC | PIP/SEFER | |

|---|---|---|

| Holdings by private-sector investors | Private | PIP |

| Foreign exchange reserves | Official | SEFER |

| Sovereign wealth funds | Official | PIP |

| Other government holdings | Official | PIP |

The PIP definition of "private" thus includes holdings of sovereign wealth funds and other government holdings that would be classified as "official" by TIC, a difference most apparent in the data on long-term debt, the more common form of foreign exchange asset. As a result of this difference in definition, the PIP-reported private holdings of long-term securities—the upper right panel of Figure 1—exceed TIC holdings. In all other panels of Figure 1, TIC holdings exceed those collected in PIP.

Country attribution and "custodial bias"

PIP collects asset data based on the foreign securities holdings of each country's residents while TIC collects data only from U.S. entities. Most notably, in the case of large custodians, the custodians' holdings of third-country residents would not be reported as holdings of U.S. assets in PIP but would be reported as holdings of the custodian country in TIC, generating both differences in overall magnitudes and differences in country attribution.

The holder country in TIC is the residence of the U.S. reporter's counterparty, which can generate differences from PIP reporting for countries with large securities depositories and significant resident investment funds. First, holdings of overseas securities depositories who typically hold securities in custody on behalf of customers from many countries are all recorded in TIC by the residence of the overseas depository. This feature of TIC data collection generates "custodial bias," or larger holdings reporting from custodial centers such as Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom.

To illustrate how these differences affect reporting, Table 2 provides a hypothetical example in which a Belgian securities depository holds U.S. assets on behalf of Chinese officials, Canadian private investors, and Belgian private investors. TIC reporting includes all of these holdings as private U.S. liabilities to Belgium ($400 billion), but Belgium would report only Belgian residents' holdings of U.S. securities in PIP ($20 billion). Neither Canadian nor Chinese reporting in PIP would capture the Canadian and Chinese holdings of U.S. securities located in a Belgian depository.

Table 2: Hypothetical Example of Custodial Reporting Belgium-based Custodian with U.S. Correspondent Holds $400 billion in U.S. Treasuries

| China (official) | Canada (private) | Belgium (private) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custodial holdings | 300 | 80 | 20 | 400 |

| TIC | 0 | 0 | 400 | 400 |

| PIP (China) | 0* | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PIP (Canada) | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| PIP (Belgium) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PIP (Total) | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

In the case of investment funds, TIC reporting again collects the data based on the residence of the fund and PIP should "mirror" by collecting data from the perspective of the fund's residence without "looking through" to the residence of the funds' investors. As a result, both data sources would suffer from similar custodial bias. TIC, however, often shows lower reporting for two reasons. First, TIC reporting coverage includes only funds with U.S. custodians whereas PIP covers reporting from all funds. Second, TIC is likely affected by underreporting for Treasuries because of the treatment of the large repo market, as noted by Barth et al. (2025).6 As a result, PIP reporting for debt in offshore financial centers can be higher than that of TIC. 7 Table 3 contains a hypothetical example of reporting for an Ireland-based investment fund. In this example, the investment fund's holdings of Treasuries are lower in TIC because of decreased reporting coverage.

Table 3: Hypothetical Example of Investment Fund Reporting Ireland-based Investment Fund with U.S. Correspondent Holds $300 Billion in U.S. Treasuries and $100 Billion in U.S. Equities

| Treasuries | Equities | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investment fund holdings | 300 | 100 | 400 |

| With U.S. custodian | 200 | 80 | 280 |

| Without U.S. custodian | 100 | 20 | 120 |

| TIC (Ireland) | 200 | 80 | 280 |

| PIP (Ireland) | 300 | 100 | 400 |

The (imperfect) mirror: TIC and PIP reporting by country

Ideally, both TIC and PIP would be released by country as well as sector of holder (official and private) and all reporting practices and definitions would align. But TIC data confidentiality restrictions and PIP / SEFER agreements on data release do not allow for this full breakdown. Table 4 summarizes the breakdowns available. In the next section, we compare data reported in TIC and PIP by country, using the imperfect mirror of total TIC reporting to PIP private reporting. Notwithstanding these factors, the reporting aligns fairly closely for many countries and it is a useful tool for assessing how the three sources of discrepancy discussed could be affecting reporting for "outlier" countries.

Table 4: TIC and PIP Reporting by Country

| Official | Private | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIC | No | No | Yes |

| PIP / SEFER | No | Yes | No |

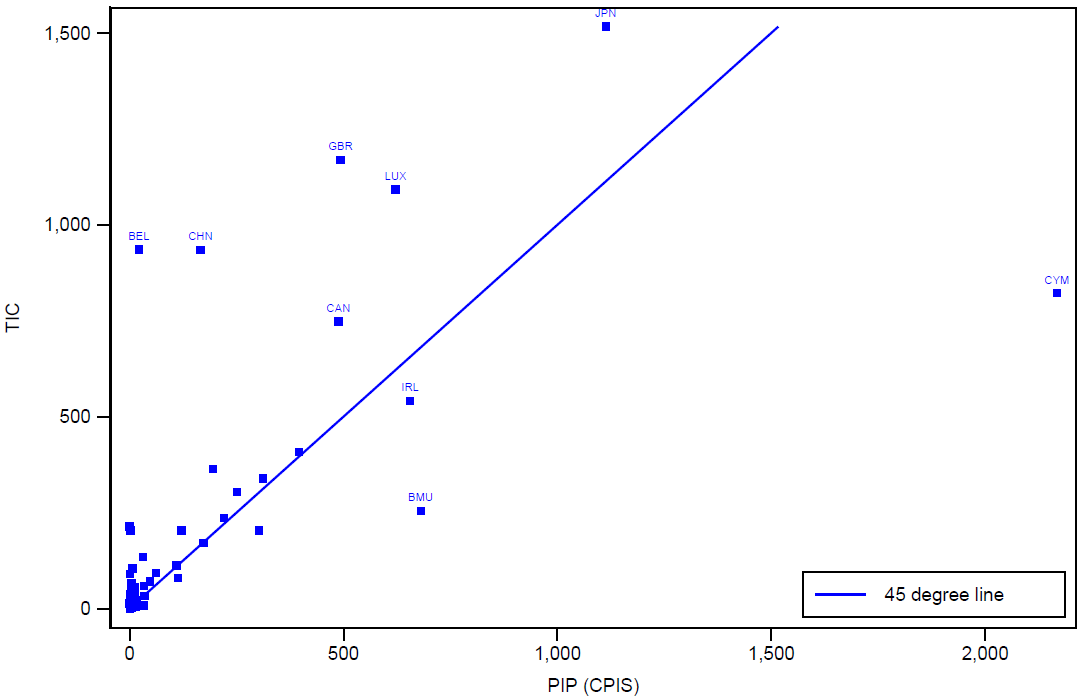

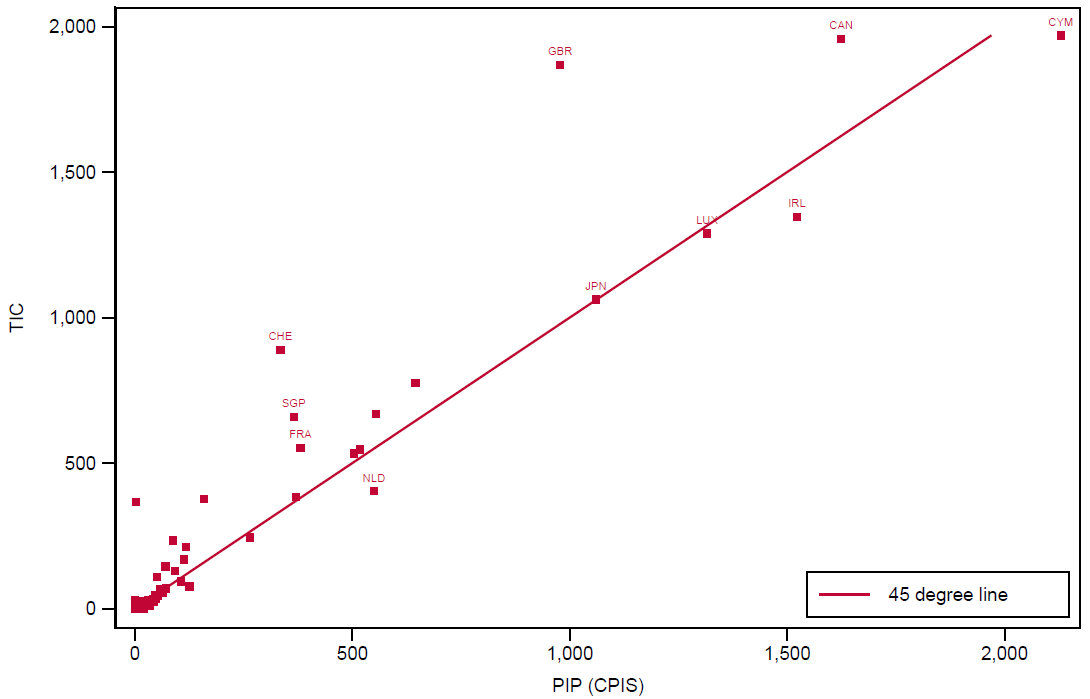

Figures 2 and 3 display scatter plots of TIC and PIP reporting by country for long-term debt and equity as of the end of 2024. Each data point is a country's reporting in TIC, the y-axis, and PIP, the x-axis. Absent the differences and limitations described above, country reporting would be the same in both datasets and the points would lie on the 45-degree line. Data points above the 45-degree line indicate that TIC reporting is higher, and data points below the 45-degree line indicate that PIP reporting is higher.8

Note. Country data points are labeled with their three-letter ISO codes.

Source: U.S. Treasury, IMF.

Based on the differences in country and sectoral reporting discussed above, we would expect outliers to fall into three groups: (1) countries with large security depositories (Belgium, Canada, Luxembourg, United Kingdom); (2) countries with a large presence of investment funds (Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Ireland); and (3) countries with large foreign exchange reserves (China, Japan). Countries in the first and second groups would be expected to show higher TIC reporting. Countries in the second group might show higher or similar reporting for equities in TIC relative to PIP, but lower reporting for debt in TIC relative to PIP. Countries in the third group would be expected to show higher TIC reporting relative to PIP. And indeed, these patterns are clear in the scatter plots. Consider first the outliers from the 45-degree line in Figure 2, which compares TIC and PIP reporting on foreign holdings of U.S. long-term debt at the end of 2024. China and Japan have much larger reporting in TIC than in PIP largely because TIC includes all holdings—both official and foreign—whereas PIP excludes their substantial foreign exchange reserves held in U.S. securities. The other notable outliers above the 45-degree line are countries with significant custodial centers. Because of the custodial bias noted above, TIC reporting attributes all holdings of these custodial centers to custodian's location rather than to the actual security owners. Below the 45-degree line, the most prominent countries are Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and Ireland, all known as offshore financial centers. TIC only captures holdings of entities with a U.S. custodian.9

Figure 3 presents country-level reporting on foreign holdings of U.S. equity by TIC and PIP for 2024.10 As with long-term debt, most of the reporting is near the 45-degree line, indicating alignment between TIC and PIP, and again the largest outliers are countries with significant custodial activity. China and Japan do not appear as outliers, indicating that equities are a less significant portion of their foreign exchange reserve portfolios relative to debt.

Note. Country data points are labeled with their three-letter ISO codes.

Source: U.S. Treasury, IMF.

Summary: Advice to Researchers

In sum, both TIC and PIP are valuable resources for research on cross-border capital flows and holdings. Researchers should be aware that the two datasets do not perfectly align for the reasons given above, and so the choice of dataset depends on the research question or focus. A few considerations might guide choice of source. PIP might be preferred for three reasons. First, PIP covers holdings of countries where neither the counterparty nor the issuing country is the United States, so it is the only option for researchers interested in studying foreign holdings of non-US securities. Second, PIP reporting for countries with large custodial centers is more accurate if researchers are interested in that country's residents' holdings of foreign securities. Third, if researchers want to focus on cross-border securities holdings excluding foreign exchange reserves, then PIP is a cleaner source. TIC might be preferred for two reasons. First, TIC holdings are likely more accurate for aggregates and for overall foreign official holdings. Second, TIC has a longer time series: although the TIC SLT collection began at roughly the same time as the CPIS (now PIP), the TIC annual securities collections go back considerably further and monthly position estimates developed by Bertaut and Tryon (2007) are available online and are included with Bertaut and Judson (2014, 2022, 2023, 2025).11 12

References

Barth, Daniel, Daniel Beltran, Matthew Hoops, Jay Kahn, Emily Liu, and Maria Perozek (2025). "The Cross-Border Trail of the Treasury Basis Trade," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 15, 2025.

Bertaut, Carol, and Ruth Judson (2025). "Measuring U.S. Cross-Border Securities Flows: Out With the Old, In with the New," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 15, 2025.

Bertaut, Carol, and Ruth Judson (2023). "Measuring U.S. Cross-Border Securities Flows: New Data and A Guide for Researchers," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 02, 2023.

Bertaut, Carol, and Ruth Judson (2022). "Estimating U.S. Cross-Border Securities Flows: Ten Years of the TIC SLT," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 18, 2022.

Bertaut, Carol, and Ruth Judson (2014), "Estimating U.S. Cross-Border Securities Positions: New Data and New Methods," Federal Reserve Board: International Finance Discussion Papers, August 2014.

Bertaut, Carol C., and Ralph Tryon (2007), "Monthly Estimates of U.S. Cross-Border Securities Positions," Federal Reserve Board: International Finance Discussion Papers 2007-910.

International Monetary Fund (2024), "Preliminary Report of the Task Team on Global Asymmetries and Results of the Stocktaking Survey (PDF)," International Monetary Fund Statistics Department, November 2024.

1. Authors can be contacted at [email protected]. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Board and Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. The same holds for flows, or transactions. The PIP system does not provide transactions data. See Bertaut and Judson (2014, 2022, 2025) for discussions of transactions data in the TIC system. As noted in Bertaut and Judson (2014, 2022, 2023, 2025) as well as elsewhere, transactions cannot be calculated from changes in holdings alone because changes in prices (valuation changes) are often significant contributors to changes in position reported at market value. Return to text

3. TIC also collects U.S. securities claims data—that is, foreign issued securities held by U.S. residents—as well as data on cross-border banking and derivatives positions. This note focuses on U.S. long-term securities positions reported monthly on TIC form SLT. Return to text

4. See IMF (2024) for this team's report as of late 2024. The work is ongoing. Return to text

5. The TIC definition of foreign official institutions is as follows: FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) (PDF) include the following:

- Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments.

- International and regional organizations.

- Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority.

6. We are grateful to the authors of Barth et al. (2025) for starting to unravel this mystery, and in particular to Daniel Beltran, one of the authors, for clarifying this point. Work to improve TIC coverage in this dimension is underway. Return to text

7. It should also be noted that reporting of U.S. securities holdings by offshore hedge funds is problematic and likely undercounted, as discussed in Barth et. al (2025). A large presence of investment funds is often associated with presence of leveraged investors, repo activity, and greater flows volatility. In addition, these funds often hold assets on behalf of investors from other countries, and thus the true nationality of investors is obscured. For example, Cayman funds predominantly channel investments from U.S. residents, and funds based in Ireland and Luxembourg funds likely channel investments from residents across Europe. Return to text

8. Countries are only shown if they are reported in both the TIC SLT monthly data and PIP, but this set of countries accounts for the vast majority of cross-border holdings. At end-2024, the countries shown account for 97.5 percent of total long-term debt and 99.1 percent of equity reported in TIC. Return to text

9. In addition, as noted in Barth et al. (2025), Cayman Islands reporting in TIC is likely significantly undercounted. Return to text

10. Patterns for other years are similar. Return to text

11. The TIC annual liabilities reports are more detailed; aggregate volumes align closely with the SLT data. Return to text

12. A note on more complete long-term time series, which will be carried in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED system, is forthcoming. Return to text

Judson, Ruth, and Nyssa Kim (2026). "Measuring Cross-Border Securities Positions: Explaining Asymmetries between U.S. Treasury TIC and IMF PIP (formerly CPIS) Data," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 13, 2026, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.4004.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.