FEDS Notes

February 06, 2026

A brief history of bank notes in the United States and some lessons for stablecoins

Prior to the establishment of the Federal Reserve, commercial banks issued "bank notes" that circulated as a privately issued form of money. In addition to being backed by the issuing bank, these notes were backed by various types of collateral, including state government bonds and U.S. government bonds. The experiences of the United States with these privately-issued, collateral-backed forms of money may provide a useful reference for thinking about issued related to stablecoins today. For instance, the historical experience highlights the role of a credible regime to convert the private notes into government issued money in shaping the value of private money.

The Free Banking Era

The period from 1837 to 1863 is known as the "Free Banking" era. In many states during this period, the establishment of a new bank was freely allowed if investors raised a certain amount of equity and met other registration requirements.1 All banks were chartered by state governments.

Each bank in the free-banking states was allowed to issue its own paper currency, commonly referred to as bank notes. These notes were liabilities of the bank, but were required to be secured by specified high-quality collateral, typically state-issued bonds or mortgage assets which were held in a security deposit account with the state banking authority (Dwyer 1996). A bank could issue notes up to the value of the assets that it had in that account; if the value of the assets in that account declined, the bank would have to add more assets or shrink its notes outstanding. Banks could earn a profit from the interest earned on assets held in their security deposit account that backed the non-interest-bearing notes. For many banks, notes represented a substantial portion of their liabilities.

Notes were redeemable in specie (gold or silver coin) or other legal tender.2 Redemption could occur at the issuing bank or at a correspondent bank in a financial center that the issuing bank maintained a formal relationship with; that correspondent bank was referred to as the redemption agent. Banks other than the redemption agent were not required to pay specie when presented with the notes of another bank. However it was typical for banks in financial centers to exchange specie for bank notes upon request if a note of another bank was presented to them, but that exchange often occurred at a discount to the face value of the bank note presented (or they would credit the bank account of the person presenting the bank note, but again at a discount to the face value of the note). The size of that discount would depend on whether the bank issuing the note was known and considered trustworthy by the bank receiving the note and the effort that the bank receiving the note would have to exert to obtain specie from the bank issuing the note (if desired).

Discounts on notes were not constant; they varied across place and over time. Local merchants had to keep track of which bank notes would be taken by their local banks and at what discount. Dealing with these issues added notably to the cost of doing business.

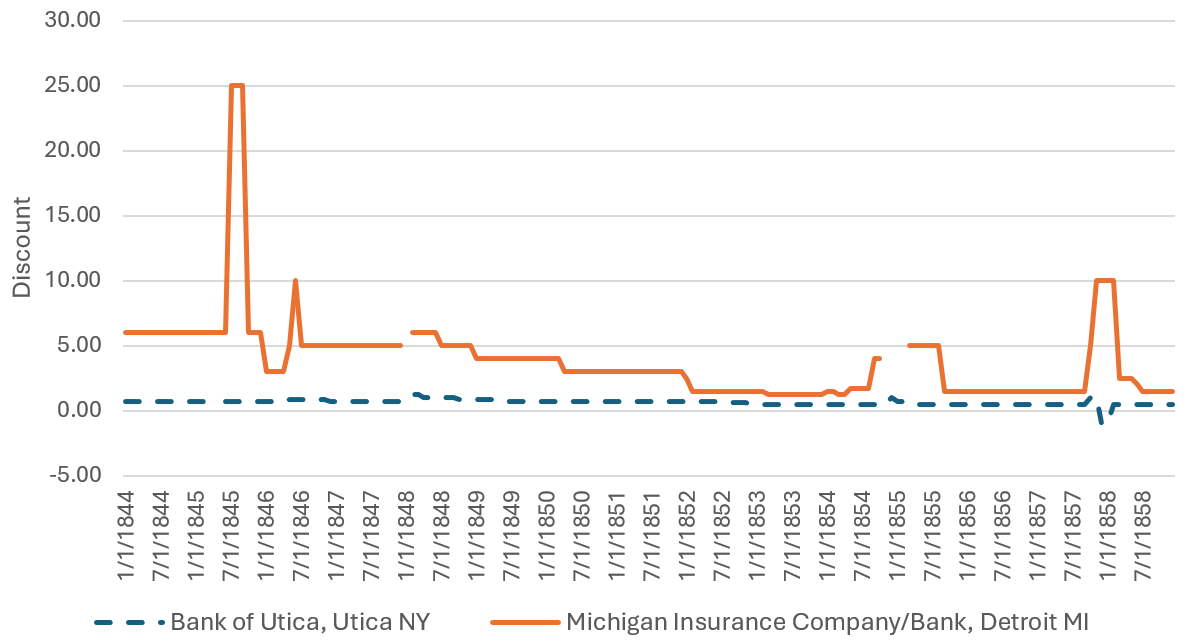

During financial stress, differences in the discounts across bank notes widened significantly (see Figure 1). Notes secured by higher quality collateral or from states with more better-quality regulations (such as New York) did not see as substantial increases in discounts. Notes secured by somewhat less high-quality collateral or from states considered to have lesser-quality governance rules (such as Michigan) tended to see discounts increase notably (Bordo 2025).

Source. Gorton, Gary B. and Warren E. Weber. Quoted Discounts on State Bank Note Discounts in Philadelphia, 1832-1858. Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

The National Banking Era

The period from 1863-1913 is known as the National Banking Era. Banks chartered by the national government, known as national banks, were able to issue bank notes. (States could continue to charter banks and these banks were also legally able to issue notes, but there was a steep federal tax on state bank notes that made such issuance unprofitable.) These national bank notes were required to be secured by Treasury securities that were held by the bank at the Treasury (indeed a small degree of overcollateralization was required). Overall, this setup was successful in creating a uniform currency (Luck 2025).

It is quite probable that the shift in the 1860s to national bank notes that had a stable and uniform value had considerable benefits for trade and finance. The Comptroller of the Currency argued that point extensively in his Annual Report for 1894. However, quantifying the benefits is extremely difficult given the other regulatory developments, new class of banks, and the economic changes wrought by the Civil War that occurred around the transition from one system to the other.

Importance of ease of redemption

One aspect of addressing one of the defects of the previous banking era was to try to eliminate the discount on the notes of particular banks and make all bank notes effectively interchangeable. Doing so took some time and adjustments to regulation. A key part of making this work was enhancing the ability of holders of the notes to convert them into specie when desired.

In the first years of the National Banking Era, notes could only be redeemed for specie at the issuing bank or at designated agent banks located in a reserve or central reserve city (a regional or national financial center). Challenges and expenses in delivering notes to a place where they could be redeemed resulted in notes of remote banks trading at a discount to par amongst financial institutions in financial centers such as New York (Friedman and Schwarz 1963, p. 21-22), but not amongst the general public.3 To enhance the ease with which the notes could be redeemed, the Treasury Department changed its procedures in 1874 to allow for the redemption of national bank notes at any sub-Treasury office throughout the country. Banks were required to have on deposit with the Treasury a redemption fund equal to 5 percent of their outstanding circulation to be used when notes were presented for redemption (James 1978). (The Treasury could then send the bank notes received to the issuing bank for specie to replenish the redemption fund.) The fact that the Treasury securities securing the notes were also held at the Treasury also meant that the notes were fully protected by the federal government in the event that the bank failed (Ennis, Wang, and Wong 2022). With this greater ease of redemption, the notes of all national banks traded uniformly at par.

The fact that all notes traded uniformly at par was key. Holders of bank notes did not need to keep track of the exchange rate between notes issued by different banks, unlike in the Free Banking Era, and indeed bank note holders could be indifferent regarding the identity of the issuing bank. The notes were interchangeable and in the terminology of Gorton (2010) were informationally insensitive.

Interestingly Canada had a similar framework where banks issued their own notes subject to backing requirements. These notes also traded at a discount when they were some distance from the issuing bank. As discussed by Fung, Hendry, and Weber (2017), to promote having the bank notes circulate at par, the Canadian government required the banks to establish redemption agencies in financial centers throughout the country. In addition, in the event that a bank suspended, the holders of notes of the suspended bank were paid interest on the notes from the day that the bank suspended until the first day that the banks made arrangements for their notes to be redeemable in specie; that encouraged any party responsible for overseeing the resolution of the suspended bank to rapidly provide for the redemption of the bank notes. These policies proved effective in ensuring that the notes of all the Canadian banks were treated uniformly and circulated at par.

Economic historians (such as Fung, Hendry and Weber 2017, Gorton and Zhang 2023) highlighted the role of the government in both the US and Canadian cases. They argue that the government did not itself guarantee the notes, but did establish rules and oversight to ensure the credibility and expediency of the banks' ability to make good on the notes they issued.

The ease with which stablecoins can be redeemed has been found to affect the deviation of the prices of the coins from par, which is reminiscent of the findings regarding historical bank notes. Typically, stablecoin holders cannot go to the issuer of the stablecoin directly to seek redemption of their notes; redemption may only be done by authorized agents. In a highly efficient system, if the price of the stablecoins were to deviate from par then the redemption agent would have an incentive to either buy stable coins in the market and redeem them with the issuing entity (in the case they are at a discount to par in the market) or obtain more stablecoins from the issuer by requesting that they be minted and sell them in the market (if the coins are trading above par). However, there are frictions associated with the redemption or minting process. Researchers have found that having more redemption agents reduces those frictions. For instance, Ma, Zeng, and Zhang (2025) find that there are fewer deviations for USDC with a large number of agents able to arbitrage between the primary and secondary markets for the coin, than for USDT, where there are few such agents. The fact that there are any deviations from par (either to the upside or downside) means that holders of stablecoins have an incentive to monitor the value of their coins and, similar to the notes in the Free-Banking Era, are not indifferent to the identity of the issuer of the particular coins that they hold.4

Issuance patterns of bank notes

National banks were subject to both minimum and maximum restrictions on note issuance. One of the puzzles from this period is that since these notes were not interest bearing and the banks retained the interest on the bonds that they held to back the notes, why did banks not always maximize the amount of issuance? Analysis of this period has provided evidence in favor of several factors. In general they point to behavior being shaped by considerations related to earnings potential and restrained by the potential for redemptions.

One factor was the size of the incentive provided by the interest that might be earned on the US bonds. Unsurprisingly, when the interest rates on the government bonds eligible to be used to secured the notes were higher, banks issued more notes.

A factor that appears to have restrained issuance was the possibility of having to deal with redemptions also appears to have affected note issuance. Banks had to hold funds in redemption sites away from the main office of the bank so that holders of the notes could trade the notes for specie at those locations; that encouraged the bank notes to trade at par. Maintaining, and if necessary replenishing the funds at these redemption sites was potentially costly. Correia (2010) considers the impact of changes in the locations of these redemption sites and finds that evidence that banks that had a greater likelihood of having to deal with more costly redemptions tended to issue fewer bank notes.

Experiences during financial instability

During the National Banking Era there were regular episodes of financial instability. There were three nationwide panics in which the normal operation of the banking system was severely disrupted and a number of minor episodes of instability.

There were risks associated with individual institutions. This was due to the fact that only part of each banks' business was issuing notes. The other, often larger, part consisted of taking deposits and making commercial loans which involved taking on some risk. At times those risks resulted in losses to the banks that caused them to become insolvent and fail. If the risks at the individual banks were correlated, for instance due to a severe recession, then bank failures could be correlated. If there were widespread concerns about bank health, systemic withdrawals—a panic—could occur. As noted by Gorton (1988) the onsets of recessions were typically correlated with banking panics.

During the National Banking Era, the United States was on the gold standard. In the early 1890s, the nation's gold reserve declined to low levels. Concerns about a possible devaluation of the US dollar resulted in a foreign exodus from US assets, that included bank notes (although the reduction in holdings of US assets was not obviously more pronounced for bank notes than for other assets). This contributed to a cascade of deterioration in financial conditions and was blamed for triggering a financial panic that closed many financial institutions and impaired economic activity (see Friedman and Schwarz 1963).

Even amid these banking panics, the public does not appear to have had concerns about the value of the bank notes themselves, at least relative to specie. While banks were suspended, secondary markets developed in which claims on frozen bank deposits could be traded at a discount to specie and bank notes. Newspaper reports regarding these secondary markets suggest that there was not a differentiation between specie and bank notes. This suggests that credible system of private money, when it is credibly backed by instruments whose value is not questioned and timely redemption is assured even in the event of default by the issuing agent, can be robust during periods of stress. The stability of the system also depended on the public's belief in the value of the underlying collateral. It is worth pointing out that none of the financial stresses in the National Banking Era raised concerns about the nominal values of the Treasury obligations that secured the bank notes.

When considering financial stability in the National Banking Era and any comparisons to what might occur under the Genius Act there are some important differences to keep in mind. As noted above, commercial banks had considerable liabilities other than bank notes and it was these other liabilities that mattered during the panics and financial crises of the era. Under the Genius Act, the stablecoin issuing entities will not have such other liabilities. Another difference is that the bank notes of this period were backed exclusively by Treasury securities, a direct obligation of the U.S. government. That was a key reason why they were stable. Under the Genius Act, stablecoin issuers may back the stablecoin assets with items other than direct obligations of the U.S. government, such as bank deposits that exceed the deposit insurance threshold.5

Transition to Federal Reserve Notes

The shift from national bank notes to Federal Reserve notes does not appear to have had significant impacts on the quality of the notes. The difference between the two periods is mainly related to the liquidity backstop provided by a central bank and "elasticity" of the currency (as noted in the preamble of the Federal Reserve Act) as the economy evolved and the demand for credit changed. The ability of the central bank to adjust the supply of liquid assets enabled the banking system to stay open during liquidity stress events and allowed the central bank to regulate the supply of money in the economy through open market operations to smooth economic fluctuations.

There was a period from 1914 to 1935 where national bank notes and Federal Reserve notes circulated simultaneously. These two types of notes appear to have been treated as interchangeable by the public and the financial sector. This is not too surprising since they were both effectively backed by the US government - national bank notes because they were backed by Treasury securities while Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the US government. Moreover, the Federal Reserve Act included provisions that encouraged the interchangeability between the two types by allowing commercial banks to deposit them at the Federal Reserve to credit their reserve account.

After Federal Reserve notes were introduced, there was quick but modest drop in national bank notes as Federal Reserve officials actively sought to swap them for Federal Reserve notes, but amid World War I financing needs, that activity ended. Subsequently, the volume of national bank notes outstanding held broadly constant as commercial banks appear not to have found it attractive to have increased issuance nor did the Federal Reserve appear to have found it necessary to remove them from circulation (see Weber 2015 for details). The national bank notes were retired from circulation in the 1930s as the Treasury redeemed without replacement the securities that were eligible to serve as collateral for the notes.

References

Bordo, Michael (2025). "The U.S. Genius Act, Stablecoins, National, State and Canadian bank notes: A Cautionary Tale," Presentation at the Hoover Institute, October 8.

Correia, Sergio (2010). "The Underissuance of National Bank Notes and the Act of June 1874," Master Thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Du, Chuan, Ria Sonawane, and Cy Watsky (2025) "In the Shadow of Bank Runs: Lessons from the Silicon Valley Bank Failure and Its Impact on Stablecoins," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 17, 2025.

Dwyer, Gerald (1996). "Wildcat Banking, Banking Panics, and Free Banking in the United States (PDF)," Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review, December, pp. 1-20.

Ennis, Huberto, Zhu Wang, and Russell Wong (2022). "A Historical Perspective on Digital Currencies," Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, 22-21.

Friedman, Milton and Anna Schwarz (1963). A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fung, Ben, Scott Hendry, and Warren Weber (2017). "Canadian Bank Notes and Dominion Notes: Lessons for Digital Currencies," Bank of Canada Working Paper 2017-5.

Gorton, Gary (1998). "Banking Panics and Business Cycles," Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 40(4), pp. 751-781.

Gorton, Gary (2010). Slapped by the Invisible Hand: The Panic of 2007, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gorton, Gary and Jeffrey Zhang (2023). "Taming Wildcat Banks," University of Chicago Law Review, pp. 909-966.

James, John (1978). Money and Capital Markets in Postbellum America, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Luck, Stephan (2025). "A Historical Perspective on Stablecoins," Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 1.

Weber, Warren (2015). "Government and Private E-Money-Like Systems: Federal Reserve Notes and National Bank Notes," Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta CenFIS Working Paper 15-03

1. The previous arrangement involved each new bank charter needing an act of the legislature. That arrangement created incentives for bribes to effectively buy local monopolies. Return to text

2. Redemption means that the presenter of the bank note would receive an amount of specie exactly equal in value to the face value of the bank note. That differs from the bank note being exchanged or exchanged for specie where the amount of specie received could be variable and determined by market forces. Return to text

3. This trading occurred between banks and "note brokers" who were involved with returning the notes to the issuing banks. The notes do not appear to have traded at a discount as far as the general public was concerned.

James (1978) reports that preferences for gold coin in California meant that there was a discount on bank notes there; however, there was also a discount on other forms of government issued paper money, like "greenback notes" so the issue appears not to have been with the bank notes themselves. Return to text

4. As documented by Du, Sonowane, and Watsky (2025), when holders of stablecoins were concerned about the credibility of the peg of some stablecoins in 2023, there was a rapid flight from those coins. That indicates that the holders of those coins were very attentive to the identity and condition of the issuers of the coins that they held. Return to text

5. In addition, the clarity of the process for redeeming the notes of failed banks has been cited as a reason for the stability of the system (see Fung, Hendry and Weber 2017, Gorton and Zhang 2023). The rules under the Genius Act for redemption of stablecoins issued by a firm that goes out of business have not yet been developed. Return to text

Carlson, Mark (2026). "A brief history of bank notes in the United States and some lessons for stablecoins," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 06, 2026, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.4001.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.