FEDS Notes

December 17, 2025

Banks in the Age of Stablecoins: Some Possible Implications for Deposits, Credit, and Financial Intermediation1

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of stablecoins, accelerated by regulatory frameworks like the Genius Act, has raised important questions about their impact on traditional banking. As these digital tokens gain mainstream acceptance, they could fundamentally reshape the structure and functions of banking and influence the established intermediation role of banks. This note explores how the expansion of payment stablecoins might affect banks across three dimensions. First, it explores how stablecoin adoption could displace deposits and alter banks' liability structures, changing banks' funding mix, liquidity risk profile, and cost of capital. Second, it analyzes the implications for credit provision by banks, including the quantity and terms of loans and the distribution of bank credit across sectors and institutions in the U.S. economy. Finally, it considers some broader structural consequences, including possible changes to banks' role in the payments ecosystem and potential shifts in the banking industry structure and competitive dynamics.

2. Effects on Bank Deposits

The impact on U.S. bank deposits depends on who demands stablecoins, what assets are converted for stablecoin purchase, and how stablecoin issuers manage reserves. Stablecoins can either reduce, recycle, or restructure bank deposits rather than simply draining them.

2.1 Sources of Stablecoin Demand and Deposit Implications

The impact of stablecoins on bank deposits depends significantly on where stablecoin demand originates, the type of funds being converted when stablecoins are purchased, and dynamics over the economic cycle. Domestic substitution of bank deposits into stablecoins may directly reduce US bank deposits, especially to the extent stablecoin issuers allocate their reserves outside of bank deposits. This substitution could be particularly pronounced among digital-native demographic segments of the population. However, foreign demand for USD stablecoins may actually increase deposits in US banks if issuers hold their reserves domestically, potentially offsetting some domestic outflows. This international dimension of stablecoin demand represents a notable difference from previous financial innovations that primarily affected domestic deposit markets.2

The type of funds being converted into stablecoins also matters considerably. Whether stablecoins primarily substitute for bank deposits or money market fund investments (among other financial instruments) affects the magnitude of impact on bank deposit levels. Early adoption patterns suggest stablecoins may initially draw more heavily from investment products before significantly impacting core deposits held at banks.3 Different adoption patterns between retail and institutional users also create varied substitution effects, with certain deposit categories facing greater substitution: Transaction accounts at banks may be more vulnerable to stablecoin substitution than savings accounts due to stablecoins' primary utility as payment instruments, particularly for younger consumers who conduct a higher proportion of transactions digitally (J.D. Power 2022). In addition, the effects are likely to differ between household retail deposits and institutional operational deposits. Retail balances tend to be more stable and relationship-driven, so substitution by households can significantly alter the composition of banks' core deposit base.

These substitution dynamics may evolve differently across economic cycles. During periods of elevated interest rates, the opportunity cost of holding non-interest-bearing stablecoins would be high, potentially slowing their adoption (Aldasoro et al. 2025). During financial stress periods, stablecoins could benefit from perceived safety or balance-sheet transparency advantages, if their reserves are viewed as less risky than bank assets (notwithstanding deposit insurance); see, for example, the flight-to-safety dynamics documented in Anadu et al. (2024). However, the relative advantage depends on the nature of the shock, and while stablecoins trade rapidly on exchanges, formal redemptions typically take longer than deposit withdrawals, so their liquidity advantage may be situational rather than universal.

2.2 Stablecoin Issuers' Asset Allocation Decisions

How stablecoin issuers manage their reserve assets should critically influence the net effect on bank deposits. If issuers hold their reserves primarily as bank deposits, this would largely maintain overall banking system size, while possibly increasing deposit concentration and a shift from insured retail deposits to uninsured wholesale deposits.4 This scenario would essentially transform the nature of bank liabilities without necessarily reducing their volume. If issuers primarily invest in other non-deposit reserve assets (such as Treasury bills, repurchase agreements, MMFs) instead, this could reduce bank deposits, though the effect depends on those assets' market equilibrium and whether counterparties to stablecoin issuers ultimately deposit proceeds back into the banking system.5

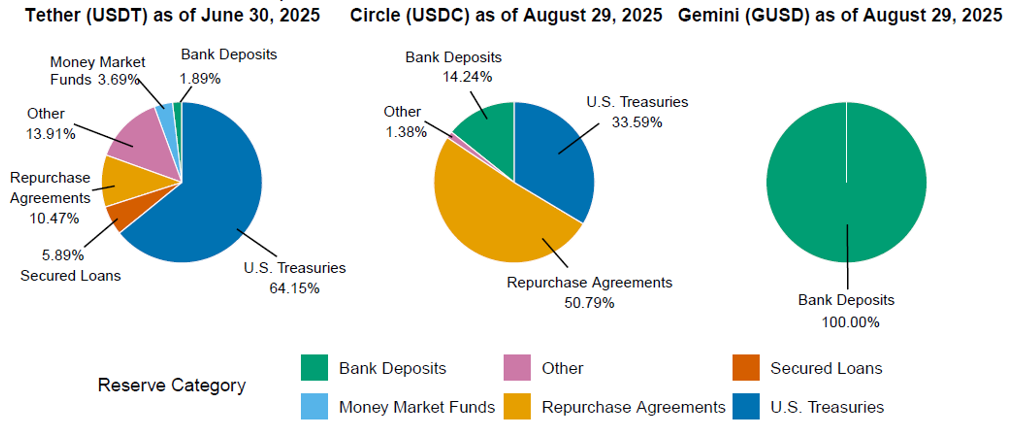

Although major stablecoin issuers maintain non-zero bank-deposit balances in their reserve mix, the share varies widely by issuer, from double-digit at Circle (around 13%), to near-zero at Tether, and bank-deposit only for GUSD; see Figure 1.6 This heterogeneity is crucial for considerations on bank deposit size and credit provision. Issuers' reserve allocation may also change going forward after the Genius Act and in response to other related regulations.

Notes: Other includes assets like non-U.S. Treasuries, other investments, precious metals/bitcoin, and issuer-specific residuals. Circle and Gemini figures exclude timing & settlement differences; remaining assets renormalized to sum to 100%. Author's own calculations

Source: Publicly available transparency reports by stablecoin issuers

Issuers' asset allocation and thus the effect on bank deposits also depend on issuers' central-bank account (Federal Reserve master account) access scenarios. When issuers have no master account access, they remain dependent on banks for payment services and reserve management. As retail deposits substitute into stablecoins, banks face more concentrated, uninsured, wholesale deposits, increasing both liquidity risk and funding costs, despite potentially limited changes in total deposits. When issuers have access to limited purpose master account, they bypass intraday correspondent banking services and keep some deposits out of banks. The most significant reduction in bank deposits would occur if stablecoin issuers gain access to master accounts that pay the IORB rate, allowing them to bypass the banking system entirely. This scenario would create highest aggregate deposit loss at commercial banks and the maximum degree of bank disintermediation, as funds flow directly from bank depositors to the central bank via stablecoin issuers without remaining in the banking system.

Finally, issuers' portfolio allocation strategies may shift during stress periods, potentially amplifying deposit volatility when banks can least afford it. During market turbulence, stablecoin issuers without direct access to master accounts might increase their allocation to bank deposits seeking safety—enhancing bank funding—and reverse course as stability returns. But if issuers are granted master account access which allows them to hold reserves directly at the Fed, the pattern could invert: funds would instead flow out of banks and into central bank balances during stress, exacerbating liquidity pressures on the banking system. In either case, such shifts could introduce new correlation risks between stablecoin growth and bank funding stability.

2.3 Effects on Deposit Composition

Stablecoin adoption affects both the level and the composition of bank deposits. As discussed earlier, deposit levels may decline when households or institutions substitute bank balances into stablecoins, especially if issuers invest reserves in non-deposit assets or gain direct access to central-bank accounts. Even when the aggregate deposit volume remains broadly unchanged, however, the underlying structure of deposits can shift substantially, with implications for funding stability, liquidity risk, and credit provision. When stablecoin issuers hold their reserves entirely as bank deposits, thereby maintaining aggregate deposit size, stablecoin growth still changes deposit composition and distribution patterns in ways that affect banks' liquidity management and credit provision.

The proportion of uninsured wholesale deposits at banks―essentially unsecured debt― could increase substantially as stablecoin issuers place large reserves with select banking partners. These wholesale deposits from stablecoin issuers would exhibit different volatility patterns compared to retail deposits. While retail deposits tend to be "sticky" due to relationship factors and switching costs, wholesale stablecoin-related deposits might move rapidly in response to market signals or redemption activity.7 The volatility changes could potentially create significant risk management challenges for banks. Asset-liability matching would become more complex with a more volatile deposit base, potentially forcing banks to hold larger liquidity buffers or shift toward more liquid assets, thus reducing the volume of loans they could originate or hold.8

Deposit concentration risks also could grow. At individual banks, the proportion of funding coming from a small number of large stablecoin issuers may increase dramatically, creating counterparty concentration that traditional diversification metrics might not fully capture. The banking system as a whole could see increased concentration as stablecoin issuers likely maintain relationships with a limited number of banking partners that have the operational capabilities and risk appetite to serve this market.

This concentration creates potential systemic vulnerabilities. If deposit flows across stablecoin-serving banks become highly correlated during periods of stress—a plausible scenario given that redemption pressures would likely affect multiple stablecoin issuers simultaneously—the resulting liquidity pressures could create contagion effects.9 The Silicon Valley Bank failure in 2023 demonstrated how quickly uninsured deposits can flee when confidence wavers; a similar dynamic could affect stablecoin-serving banks during periods of crypto market turbulence.

2.4 Banks' Competitive Responses

Banks are unlikely to remain passive as stablecoins gain market share. As deposit competition intensifies, banks may be expected to deploy strategies to defend customer relationships and their funding base.

Interest rate adjustment is the most immediate response. Banks facing deposit pressure from stablecoins, especially from stablecoin rewards, may segment their deposit offerings more granularly, providing higher yields for categories most vulnerable to substitution while maintaining lower rates on more stable funding sources.

Technological innovation forms another critical response. Many banks are developing tokenized deposit products that aim to combine the convenience and programmability of digital tokens with the regulatory protections of traditional banking services. JPMorgan's JPMD is an example of this approach, while other firms are also piloting consumer-facing tokenized deposit products that offer integration with fast payments and digital wallets.

Enhanced payment functionalities are also emerging as a defensive strategy. Banks are accelerating adoption of instant payment rails like FedNow and RTP while improving their mobile interfaces to match the user experience offered by fintech competitors. The goal is to reduce the convenience advantage that stablecoins might otherwise enjoy in payment contexts.

Strategic partnerships with stablecoin issuers represent another adaptation pathway for banks, allowing them to stay connected to digital payment flows through custody services, settlement accounts, and even white-label banking infrastructure. In a white-label model, the bank provides the regulated deposit and payment infrastructure behind the scenes, while the stablecoin platform presents the service under its own brand, enabling banks to earn fee income and retain some deposit relationships.10

Regulatory arbitrage monitoring has also become a priority for banks. As banks operate under more stringent regulatory frameworks than many stablecoin issuers, they are actively engaging with policymakers to ensure competitive equity. This includes advocating for consistent application of regulatory principles like "same activity, same risk, same regulation" to prevent stablecoin issuers from gaining unfair advantages through regulatory disparities; see, for example, comment letters about the Genius Act by the Bank Policy Institute.

The effectiveness of these responses will likely vary across bank sizes, with larger banks generally better positioned to invest in technological solutions or form strategic partnerships with stablecoin issuers. Regional and community banks may need to emphasize relationship advantages and local market knowledge to retain deposits in the face of digital alternatives.

3. Effects on Bank Credit Provision

The migration of deposits toward stablecoins can influence bank credit provision through three interconnected channels: reductions in aggregate deposit volumes, shifts in deposit composition, and changes in funding costs and distributional patterns. Together, these channels determine how stablecoin adoption affects banks' balance-sheet capacity, risk-taking behavior, and willingness to provide credit. Lower or more volatile deposits constrain credit provision and raise liquidity-management costs, prompting portfolio rebalancing, tighter lending standards, and higher loan pricing. Because the effects vary by bank size and funding structure, stablecoin growth may not only compress aggregate credit supply but also redistribute credit availability across borrowers, sectors, and regions, reinforcing structural heterogeneity in U.S. banking.

3.1 Balance Sheet Capacity and Asset Allocation Adjustments

Shifts in deposit levels directly influence banks' ability to supply credit by constraining balance sheet capacity. Because deposits underpin credit creation and maturity transformation, a sustained migration of these funds into stablecoins reduces the funding available for loan growth unless alternative liabilities are secured. Importantly, the impact on lending can exceed the size of the initial outflow. Banks fund long-term, relatively illiquid assets (loans) with short-term liabilities (deposits, mostly), so each dollar of deposit withdrawal can lead to a more-than-one-dollar contraction in lending as institutions rebalance to meet liquidity, leverage, and capital requirements (Kashyap and Stein, 2000; Drechsler et al., 2021). This amplification would likely be more pronounced among banks with high loan-to-deposit ratios or those already operating close to regulatory thresholds.

Empirical evidence confirms that funding shocks for banks generally translate into significant reductions in credit supply, especially to smaller firms (potential borrowers) and among banks that are more reliant on wholesale funding. In their seminal paper, Khwaja and Mian (2008) use Pakistani data to show that a 1% decline in deposits leads to a 0.6% reduction in lending to the same borrower; while large firms are able to compensate this loss by additional borrowing through the credit market, small firms face large drops in overall borrowing. Several U.S.-based studies reinforce these findings. Ivashina and Scharfstein (2010) show how funding pressures on banks during the 2008 financial crisis led to reduced lending, with those more reliant on wholesale funding cut lending more than those with stable deposit bases. Similarly, Cornett, McNutt, Strahan, and Tehranian (2011) and Dagher and Kazimov (2015) find that banks more reliant on wholesale funding reduced lending more severely following the global financial crisis, highlighting how retail deposits can cushion lending during negative shocks. Gilje, Loutskina, and Strahan (2016) find banks experiencing deposit inflows during shale booms increased lending activity. Focusing on aggregate effects, Kundu, Park, and Vats (2025) estimate a money multiplier of 1.26 by constructing deposit shocks from local natural disasters and employing a granular-instrumental-variable approach. Their findings indicate that a $1 decline in deposits leads to a $1.26 reduction in lending, demonstrating the amplified impact of deposit outflows on credit provision.

As retail deposit funding erodes, banks may move toward greater reliance on wholesale borrowing and capital-market instruments. These sources are typically costlier and more sensitive to market conditions, raising banks' funding costs and compressing their net interest margins. Because retail deposits are both cheaper and more stable for banks, they underpin the traditional banking model in which "sleepy" deposits finance longer-duration, illiquid loans and credit lines, creating a comparative advantage over other intermediaries (Hanson, Shleifer, Stein, and Vishny, 2015; Kashyap, Rajan, and Stein, 2022). When funding shifts away from such deposits, this advantage weakens.

Even if aggregate deposit volumes remain unchanged, a shift in their composition toward wholesale or uninsured deposits—which behave more like unsecured short-term debt—increases funding volatility and liquidity risk. Banks typically respond by rebalancing their balance sheets to match the risk profile of their liabilities: shortening asset duration, raising liquid asset buffers, and scaling back activities that involve substantial maturity transformation, such as fixed-rate mortgages, multi-year commercial loans, and project finance facilities. These adjustments reduce the supply of longer-term credit even in the absence of an outright decline in total deposits.

Regulatory requirements could reinforce these adjustments. Under the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), deposits from stablecoin issuers, which are classified as wholesale and typically uninsured, carry higher runoff assumptions, requiring banks to hold larger stocks of high-quality liquid assets and reduce the proportion of liabilities deployable for lending, especially longer-term credit. The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) similarly imposes higher funding requirements for long-term lending when a bank's liabilities appear less stable.11 These constraints can tighten credit conditions in the banking sector even if total deposit levels are unchanged.

Banks' internal risk-management systems can further propagate these effects. Funds transfer pricing (FTP) models would likely assign higher internal costs to business lines relying on volatile funding, lowering the profitability of longer-term lending and discouraging such activities. As a result, changes in deposit composition—independent of overall balance-sheet size—can significantly reduce the volume, maturity, and risk appetite of bank credit provision.

In addition, the distribution of deposits across banks may evolve as stablecoin activity grows. Some institutions, particularly large custodial or settlement banks, could specialize in servicing stablecoin issuers and thus attract a disproportionate share of these concentrated, operational deposits. Such banks typically maintain more conservative asset-allocation profiles, favoring short-term, highly liquid securities over longer-term loans. Consequently, even if the total volume of deposits in the banking system remains unchanged, a shift in deposit ownership toward liquidity-focused banks could reduce the overall degree of credit provision by the system as a whole.

3.2 Back-of-the-Envelope Calculations on the Effect of Loans

A simple back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests a possibly material effect on bank loans. Let $$\Delta SC$$ be the gross shift into USD stablecoins (from U.S. residents unless noted). Let $$\alpha$$ be the share of issuer reserves kept as bank deposits (recycling back to banks). Let $$FO$$ be the net foreign offset that adds bank deposits (e.g., foreign users of USD stablecoins when reserves are left at U.S. banks). The net deposit drain is $$\Delta D\approx-(1-\alpha)\Delta SC + FO$$. The credit supply effect purely based on the effect on deposit level is $$\Delta L\approx m\cdot\Delta D$$, where $$m$$ is the money multiplier, or the "deposit-to-lending" pass-through. Based on the estimates from Khwaja and Mian (2008) and Kundu, Park, and Vats (2025), the empirical range is $$m \approx$$ 0.6–1.26.

If the α share of issuers' deposits recycles as wholesale/operational deposits, banks face higher runoff factors, which means bigger HQLA buffers and less balance-sheet room for loans. For a back-of-the-envelope calculation, we can apply a simple composition haircut. Let $$\gamma$$ be the incremental "non-deployable" fraction on recycled wholesale balances; we can assign $$\gamma$$ = 5–15% with the order-of-magnitude reflecting LCR runoff and internal FTP penalties. The composition effect on loans is therefore $$\Delta L_{comp}\approx -\gamma\cdot\alpha\cdot\Delta SC$$. The total effect on loans is then $$\Delta L_{total}\approx\Delta L+\Delta L_{comp}\approx m\cdot\Delta D-\gamma\cdot\alpha\cdot\Delta SC$$.

We can consider several scenarios to illustrate the calculation.

Scenario A — Low adoption, high recycling

- Assumptions: $$\Delta SC$$ = $200B; $$\alpha$$ = 50% (issuers keep half as bank deposits); $$FO$$ = 0.

- Net drain: $$\Delta D=-(1-0.5)\cdot200=-$100B$$.

- Level effect: $$\Delta L=m\cdot(-$100B)= -$60B\ to -$126B$$.

- Composition haircut: $$\Delta L_{comp}=-\gamma\cdot0.5\cdot200$$.

- With "$$\gamma$$" = 5–15% → –$5B to –$15B.

- Total: –$65B to –$141B in bank loans.

Scenario B — Moderate adoption, low recycling, some foreign offset

- Assumptions: $$\Delta SC$$ = $500B; α = 20%; $$FO$$ = +$100B.

- Net drain: $$\Delta D=-0.8\cdot500+100=-$300B$$.

- Level effect: –$180B to –$378B.

- Composition haircut: $$\Delta L_{comp}=-\gamma\cdot0.2\cdot500=-$10B\ {to}\ –$30B$$.

- Total: –$190B to –$408B.

Scenario C — High adoption + master-account access paying IORB (max disintermediation)

- Assumptions: $$\Delta SC$$ = $1T; $$\alpha$$ = 0 (no recycling to banks); $$FO \approx$$ 0.

- Net drain: $$\Delta D$$=-$1T.

- Level effect: –$600B to –$1.26T.

- Composition haircut: ~0 (no recycled deposits).

- Total: –$600B to –$1.26T.

Taken together, for each $100 billion of net deposit drain not recycled to banks, empirical pass-throughs imply a $60 to $126 billion contraction in bank lending based on empirical estimates of the money multiplier, with an additional $0 to $15 billion composition-driven reduction if the recycled balances take wholesale form under LCR/NSFR assumptions. Scaling to plausible adoption paths gives contractions in loan provision of $65 to $141 billion in a low adoption case, $190 to $408 billion in a moderate adoption case, and $600 billion to $1.26 trillion in a high adoption case with issuers access to master-account. Overall, the scale of stablecoin adoption is important. The ratio of recycling to bank deposits $$\alpha$$ is pivotal, as higher $$\alpha$$ shrinks the level hit but increases composition costs. In addition, $$FO$$ (foreign offset) can materially blunt the drain if reserves stay in U.S. banks. Finally, money multiplier $$m$$ (deposit-to-loan pass-through) directly changes loans.

3.3 Loan Pricing, Distributional Effects, and Bank Heterogeneity

The effects of stablecoin-driven deposit shifts on bank credit provision extend beyond aggregate loan volumes to include changes in pricing, the distribution of lending across institutions and sectors, and heterogeneous effects across bank sizes.

While increased funding volatility and a rising share of uninsured deposits would likely reduce the overall supply of bank credit, these pressures could also manifest in new loan pricing dynamics. As banks turn to more expensive or volatile funding sources to replace lost deposits, they are likely to pass on a significant portion of those costs to borrowers. Evidence indicates that over 60% of increases in banks' funding costs are transmitted into their lending interest rates, though competitive pressures may prevent full pass-through in some markets.12 Higher spreads could particularly affect sectors that depend heavily on bank credit—such as small business financing and commercial real estate—amplifying credit constraints even without a dramatic reduction in loan supply per se.

The distributional consequences of these dynamics vary widely across borrower types and economic sectors. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which rely heavily on relationship banking, are especially vulnerable because the economics of relationship lending become less attractive when funding costs rise and volatility increases. Commercial real estate lending, which involves long-term commitments and significant maturity transformation, is also highly sensitive to shifts in funding stability. By contrast, large corporations with capital market access may substitute toward bond issuance or nonbank lenders, limiting their exposure to changes in bank intermediation capacity. These differences could widen credit disparities across firms and regions, potentially affecting economic growth patterns if stablecoin adoption reaches significant scale.

Heterogeneity in the impact might also be expected across different segments of the banking industry. Large banks are generally better positioned to adapt, thanks to diversified funding bases, stronger access to wholesale markets, and more sophisticated balance sheet management tools. Many are also actively investing in digital capabilities—such as tokenized deposit products or custody services for stablecoin issuers—that allow them to recapture revenue streams and sustain client relationships despite deposit outflows. Mid-sized regional banks, by contrast, may face the greatest vulnerabilities. They often lack both the scale advantages of large institutions and the relationship depth of community banks, while having limited access to alternative funding markets. Those with high concentrations in commercial real estate or tech-oriented markets could face disproportionately severe funding shocks and credit contractions.

For smaller community banks, the picture is likely to be more mixed. Institutions serving primarily retail and small business customers in which deposits serve as a key component of the bank-customer relationship may be less affected by stablecoins, especially in less digitally oriented regions. Other banks, particularly those operating in deposit markets with younger, more tech-savvy populations, may face significant deposit substitution without ready access to replacement funding. Because they rely more heavily on deposits and have fewer alternatives, such banks may be forced to contract lending more sharply or substantially increase loan pricing. While many community banks face challenges from stablecoin adoption, others are proactively positioning themselves within the ecosystem. Some have begun initiating stablecoin issuance partnerships, providing banking services to stablecoin issuers, or developing their own stablecoin initiatives.13

Together, these dynamics suggest that stablecoin adoption could reshape the landscape of bank credit provision in both quantitative and qualitative ways. The aggregate supply of credit is likely to decline, lending costs may rise, and access to financing could become more uneven across borrower types, sectors, and regions. Moreover, the uneven capacity of banks to adapt may accelerate ongoing trends toward industry consolidation, as those unable to manage deposit volatility or fund balance sheet growth face increasing competitive pressure.

4. Other Effects on the Banking Sector

Beyond their implications for deposit-taking and lending, stablecoins may significantly reshape banks' roles in the payments landscape. By offering low-cost, near-instant, 24/7 settlement, stablecoins compete directly with traditional bank payment services, including products such as Real-Time Payments (RTP) and FedNow, which have historically generated fee income for banks and strengthened their relationships with customers. The programmability and interoperability with digital wallets promised by stablecoins could make them particularly attractive for cross-border transactions, micropayments, and decentralized finance applications, where conventional payment rails offered through banks remain costly or slow.

At the same time, stablecoins could also serve as complements rather than pure substitutes. Banks may partner with stablecoin issuers, integrate tokenized payment options into their platforms, or provide settlement accounts and custodial services that support stablecoin infrastructure. Such partnerships could allow banks to maintain relevance in the payments space while capturing new fee-based revenue streams.

Perhaps most fundamentally, widespread stablecoin adoption could accelerate the functional unbundling of banking services, separating to a greater extent payments functions facilitated through banks from banks' traditional credit intermediation role. Historically, payment services have acted as a key point of customer acquisition and relationship management for banks, anchoring demand for deposits and facilitating, for example, cross-selling of credit and wealth-management products. If stablecoins reduce reliance on bank payment systems, this longstanding linkage between payments and lending could weaken, prompting banks to rethink how they engage customers and monetize their services. However, the effect may be more limited if banks continue to provide the on- and off-ramp infrastructure to facilitate conversions between deposits and stablecoins, while stablecoin networks primarily handle on-chain settlement.

5. Conclusion

The rise of stablecoins presents challenges and opportunities for traditional banking. While their growth does not signal the end of the banking model, it has the potential to accelerate structural shifts in financial intermediation, including changes in deposit and funding costs, different patterns of credit provision, and new dynamics in payment services. The ultimate trajectory will depend on how regulatory frameworks evolve, how effectively banks adapt, and whether stablecoins transition from niche speculative instruments to widely adopted payment and settlement tools.

Banks that move proactively, particularly large institutions with the scale, technological capacity, and regulatory expertise to participate in the stablecoin ecosystem, may not only offset potential disintermediation but also develop new revenue streams and customer engagement models. These could include issuing tokenized deposits, offering custodial and settlement services, or integrating programmable payment solutions into existing platforms. Smaller and less digitally advanced institutions, by contrast, may face more serious headwinds. Erosion of their deposit base and rising funding costs could weaken their lending capacity, particularly in markets where relationship banking has been central to local credit provision.

References

Aldasoro, Iñaki & Cornelli, Giulio & Ferrari Minesso, Massimo & Gambacorta, Leonardo & Habib, Maurizio Michael, 2025. "Stablecoins, money market funds and monetary policy," Economics Letters, Elsevier, vol. 247(C).

Anadu, Kenechukwu, Pablo D. Azar, Marco Cipriani, Thomas M. Eisenbach, Catherine Huang, Mattia Landoni, Gabriele La Spada, Marco Macchiavelli, Antoine Malfroy-Camine, and J. Christina Wang. 2023. "Runs and Flights to Safety: Are Stablecoins the New Money Market Funds?" Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports 1073, September.

Cornett, Marcia Millon, Jamie John McNutt, Philip E. Strahan, and Hassan Tehranian. 2011. "Liquidity Risk Management and Credit Supply in the Financial Crisis." Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2): 297-312.

Coste, C.-E. 2024. "Toss a Stablecoin to Your Banker: Stablecoins' Impact on Banks' Balance Sheets and Prudential Ratios." ECB Occasional Paper Series 353. European Central Bank.

Dagher, Jihad, and Kazim Kazimov. 2015. "Banks' Liability Structure and Mortgage Lending During the Financial Crisis." Journal of Financial Economics 116(3): 565–582.

Gilje, Erik P., Elena Loutskina, and Philip E. Strahan. 2016. "Exporting Liquidity: Branch Banking and Financial Integration." Journal of Finance 71 (3): 1159-1184.

Hannan, Timothy H., and Gerald A. Hanweck.1988. "Bank Insolvency Risk and the Market for Large Certificates of Deposit." Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 20(2): 203-211.

Hanson, Samuel G., Andrei Shleifer, Jeremy C. Stein, and Robert W. Vishny. 2015. "Banks as Patient Fixed-Income Investors." Journal of Financial Economics 117(3): 449–469.

Harimohan, Renuka, Michael McLeay, and Tomasz Young. 2016. "Pass-through of Bank Funding Costs to Lending and Deposit Rates: Lessons from the Financial Crisis." Bank of England Staff Working Paper 590. Bank of England.

Ivashina, Victoria, and David Scharfstein. 2010. "Bank Lending During the Financial Crisis of 2008." Journal of Financial Economics 97 (3): 319-338.

Kashyap, Anil K., and Jeremy C. Stein. 2000. "What Do a Million Observations on Banks Say about the Transmission of Monetary Policy?" American Economic Review 90 (3): 407–428.

Kashyap, Anil K., Raghuram G. Rajan, and Jeremy C. Stein. 2022. "Banks as Liquidity Providers: An Explanation for the Coexistence of Lending and Deposit-Taking." Journal of Finance 77(3): 1091–1124.

Khwaja, Asim Ijaz, and Atif Mian. 2008. "Tracing the Impact of Bank Liquidity Shocks: Evidence from an Emerging Market." American Economic Review 98 (4): 1413–1442.

Kundu, Shohini, Seongjin Park, and Nishant Vats. 2025. "The Geography of Bank Deposits and the Origins of Credit Supply." Working paper.

Maechler, Andrea M., and Kathleen M. McDill. 2006. "Dynamic Depositor Discipline in US Banks." Journal of Banking & Finance 30 (7): 1871-1898.

Office of Financial Research. 2023. Liquidity Coverage Ratios of Large U.S. Banks During and After COVID-19. OFR Brief 24-02. Washington, DC: Office of Financial Research.

1. I thank Mark Carlson, Margaret DeBoer, Sam Hempel, Felicia Ionescu, Elizabeth Klee, Michael Lee, Matthew Malloy, Michael Palumbo, JP Perez-Sangimino, Alexandros Vardoulakist, Annette Vissing-Jorgensen, and Min Wei for helpful suggestions, and Meghan Carpenter for assisting with chart. Return to text

2. In a Brookings overview, it is noted that in countries with volatile local currencies (e.g. Argentina, Nigeria, Turkey), stablecoin usage has grown as people "save" in dollar-pegged tokens. For example, in a 2024 Visa-sponsored survey across Brazil, Turkey, Nigeria, India, and Indonesia, about 47% of crypto-technology users reported using stablecoins (or digital dollars) to save. Return to text

3. Anadu et al. (2024) provides evidence of flight-to-safety within stablecoins, suggesting stablecoins behave more like investment vehicles akin to money-market funds (MMFs) than core deposits. Aldasoro et al. (2025) find U.S. monetary-policy shocks lead to inflows into prime MMFs and outflows from stablecoins, indicating a substitution margin between stablecoins and MMFs. Similarly, when market turns bearish, demand for stablecoins falls, pointing to investment-style usage and substitution with other yield-bearing cash-equivalents. Return to text

4. Coste (2024) show that from a regulatory-mechanics angle, deposits from stablecoin issuers are treated as wholesale/financial-sector liabilities with higher outflow rates, i.e., noncore-type funding. Return to text

5. This mechanism resembles that of money market funds, which historically diverted funds from bank deposits into government securities. Return to text

6. Stablecoin issuers rarely disclose the exact interest rates on their reserve deposits. Available information suggests these are institutional scale, negotiated rates that may be slightly below comparable market yields, reflecting banks' provision of custodial and settlement services alongside liquidity access. Return to text

7. Data suggest wholesale funding can be two to three times more volatility than retail deposits, particularly during stress periods; see, for example, Office of Financial Research (2023) and Coste (2024). Similarly, Hannan and Hanweck (1988) find uninsured depositors require higher interest rates at riskier banks, and Maechler and McDill (2006) suggest uninsured depositors might not supply liquidity to weak banks at any price. Return to text

8. Internal funds transfer pricing systems may need recalibration to account for the different volatility of stablecoin-related deposits, potentially creating internal tensions between relationship managers seeking to attract these deposits and risk managers concerned about their stability. Return to text

9. While existing supervisory tools like liquidity stress testing and concentration limits provide some protection, they were not specifically designed to address the unique dynamics of stablecoin-related deposits. The velocity with which these funds can move due to the 24/7 nature of crypto markets presents particular challenges for traditional bank liquidity monitoring systems. Return to text

10. For example, Circle partners with banks such as BNY Mellon and Customers Bank to hold portions of USDC reserves and manage settlement flows; Paxos maintains stablecoin reserves at institutions including State Street, BMO, and BNY Mellon; and banks like Cross River Bank and Evolve Bank & Trust provide white-label banking infrastructure to fintech and digital-asset platforms, enabling them to offer payment and deposit services under their own brand. Recent developments further illustrate this trend: the U.S. large-bank consortium behind Zelle has announced plans to expand to international payments using USD stablecoins. Citigroup also formed a partnership with Coinbase to provide stablecoin payment capabilities for institutional clients globally, bridging fiat and stablecoins. Return to text

11. While the actual behavior of these balances may depend on how the corresponding stablecoins are used—for instance, retail payment activity might generate more stable transaction flows than wholesale settlement uses—the regulatory framework treats them uniformly as wholesale deposits. As a result, it is the regulatory classification rather than observed behavior that primarily constrains banks' balance-sheet capacity, tightening credit conditions even if total deposit levels remain unchanged. Return to text

12. Lombardi & Mizen (2015), constructs a weighted-average cost of liabilities (WACL) for 11 European countries and estimates long-run pass-through from funding costs to lending rates of roughly 0.66–0.87, with heterogeneity across countries and products. Harimohan, McLeay & Young (2016) find rapid/near-complete pass-through for common funding-cost shocks but slower, incomplete pass-through for bank-specific cost changes influenced by competition. Return to text

13. For example, Customers Bank partnered with Figure Technologies to offer blockchain-based payment solutions and stablecoin capabilities. Similarly, The Provident Bank developed strategic partnerships with cryptocurrency firms and provided banking services to stablecoin issuers. Return to text

Wang, Jessie Jiaxu (2025). "Banks in the Age of Stablecoins: Some Possible Implications for Deposits, Credit, and Financial Intermediation," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 17, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3970.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.