FEDS Notes

August 25, 2025

Decoding the Productivity Puzzle: A New Perspective on the Relationship between Remote Work and Productivity

Over the past decade, the relationship between remote work and productivity has drawn increasing attention from researchers, especially after the unprecedented shift to remote work following the COVID-19 pandemic. A growing body of literature suggests that remote work enhances productivity by offering employees greater autonomy, reducing commute times, and minimizing workplace distractions.2 At the same time, other studies point to several downsides, including weakened team cohesion, communication breakdowns, increased risk of burnout, and greater feelings of isolation—all of which can undermine long-term performance.3 These mixed findings underscore a "productivity puzzle:" the challenge of determining when, how, and for whom remote work supports or undermines productivity.

This note revisits the link between remote work and productivity by shifting the focus from remote work adoption to a less explored but key factor: the inherent ability to work remotely. By emphasizing task-based measures of remote work ability—rather than whether individuals actually engage in remote work—the analysis mitigates concerns about the selection bias stemming from unobserved worker attributes, such as motivation or skill, first emphasized by Emanuel and Harrington (2024).4 This methodological shift enhances the robustness of the findings, enabling a clearer identification of the causal effect of remote work ability on productivity outcomes.

Building upon this intuition, the baseline model relates sector-level productivity to the share of employment with the ability to work remotely in a sector and explores how the link evolves over time,

Model (1):

$$$$ y_{st}=\alpha+\beta_j\cdot \text{Remote Share}_{s,t-j}+d_s+d_t+\varepsilon_{st},\ \ \ j=0,1,\ldots\ (1) $$$$

where $$y_{st}$$ denotes (labor or multifactor) productivity in sector $$s$$ at time $$t$$, and $$\text{Remote Share}_{s,t-j}$$ is the share of employment that has access to remote work at time $$t-j$$, $$j=0,1,\ldots$$, according to occupation-level task data from the O*Net survey. Specifically, I quantify remote ability based on the importance of tasks involving remote communication—such as using email, writing memos, and making phone calls—as in Montenovo and others (2020) and then match this classification to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Current Population Survey to construct remote-ready employment shares for each sector since 2003.5

Model (1) also includes sector- and time-fixed effects to control for persistent sectoral characteristics as well as common shocks across sectors that could otherwise drive productivity or the ability to work remotely.

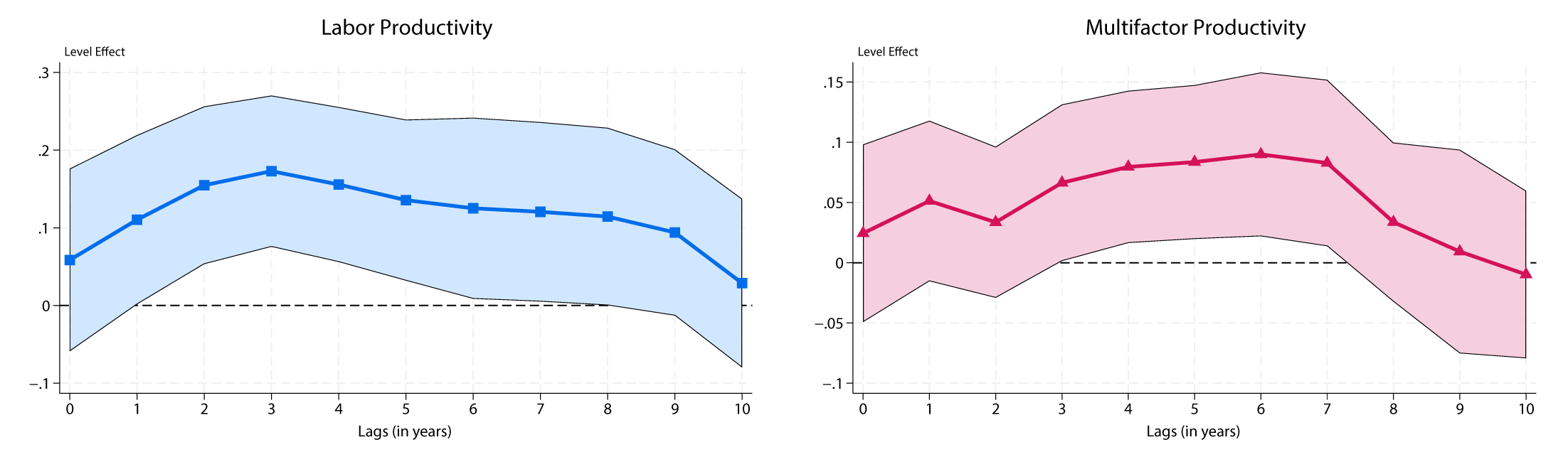

Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of the impact of remote ability on productivity, presenting the effects over 10 years; each marker denotes the productivity effects associated with remote ability as of year $$t-j$$, while the shaded area represents the 95 percent confidence interval. Crucially, productivity gains from changes in remote work ability do not materialize immediately; instead, they are subject to some lags, which may explain why previous studies, especially those centered around sudden remote work adoption during crises like COVID-19, have struggled to find consistent results. While the contemporaneous relationship between remote work ability and productivity measures is statistically insignificant, subsequent estimates indicate a consistent positive association: I find that the effect on labor productivity peaks after approximately three years, while the impact on multifactor productivity hits its maximum around the six-year mark.

Notes: Left Panel - Point estimates of the effect of remote ability on labor productivity, controlling for year- and 4-digit NAICS fixed effects. Shaded area denotes 95 percent confidence interval. Right Panel - Point estimates of the effect of remote ability on multifactor productivity, controlling for year- and 4-digit NAICS fixed effects. Shaded area denotes 95 percent confidence interval.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (USDOL/ETA).

Thinking about magnitudes, the coefficient estimates imply that an increase in remote ability of one standard deviation—or approximately an expansion in the share of remote-ready employment by 20 percent—raises labor productivity by 20 percent of a standard deviation after three years and multifactor productivity by a similar amount after six years.

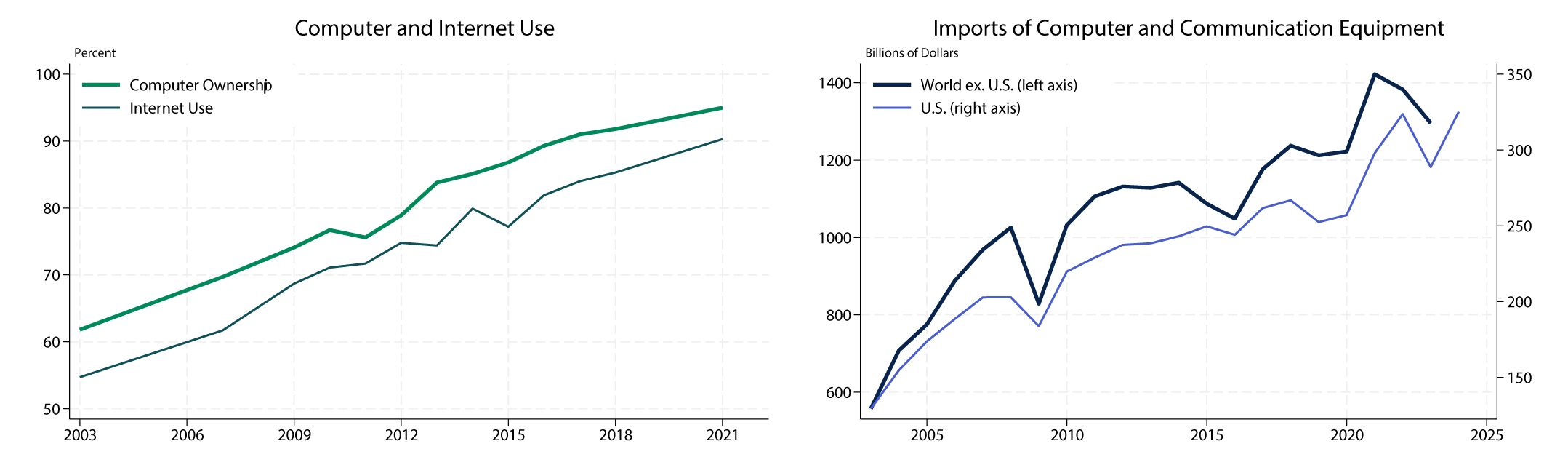

These productivity gains likely arise from the broader technological trends that may have steadily expanded remote work ability over time. Indeed, over the past two decades, the expansion in remote work ability has closely mirrored the rapid growth in computer ownership, internet access, and the imports of high-tech goods. As households and workplaces increasingly adopted personal computers and broadband internet (left panel of Figure 2), the feasibility of performing work tasks remotely may have improved substantially. In turn, the sharp rise in imports of high-tech capital goods—specifically, computer and communication equipment, right panel—has likely been a key driver of technological adoption across households and firms. In all, occupations that rely heavily on communication tools amenable to digitization—specifically, email, memos, and phone calls, which are characteristics at the core of the definition of remote work ability—are likely to have benefited significantly from these trends. Consistent with this intuition, there are indeed strong correlations (above 0.7) between the share of remote-ready employment and the rates of computer adoption, internet use, and the volume of U.S. imports of high-tech capital goods.

Notes: Left Panel Notes - Percent of households. Data through 2012 and for 2014 are from the Current Population Survey, while data for 2013 and from 2015 are from the American Community Survey. Right Panel Notes - Nominal imports of products classified in computer and communication equipment for specific country groups.

Suorce: Left Panel Source - Source: BLS and U.S. Census Bureau. Right Panel Source: World Bank.

These trends also provide a basis for assessing the robustness of the empirical link between remote ability and productivity. Although the measure of remote ability abstracts from individual self-selection into remote work adoption, it may still respond to unobserved characteristics that drive productivity growth. For example, factors such as organizational practices, workforce composition, or industry dynamics could simultaneously influence the following: the share of employment in occupations with the ability to work remotely; the extent to which those occupations rely on tools like memos, phone calls, and email; and productivity.

To address these endogeneity concerns, I develop an IV strategy that leverages the strong correlation between U.S. imports of computer and communication equipment and global (ex. U.S.) trade patterns for these products to predict remote ability. This correlation—highlighted by the parallel movements of the U.S. and global trade trends shown in the right panel—likely reflects global demand factors, including the synchronized adoption of similar technologies across countries. As a result, imports of computers and communication equipment for all countries excluding the U.S. may influence domestic remote ability but are arguably uncorrelated with U.S.-specific productivity dynamics.

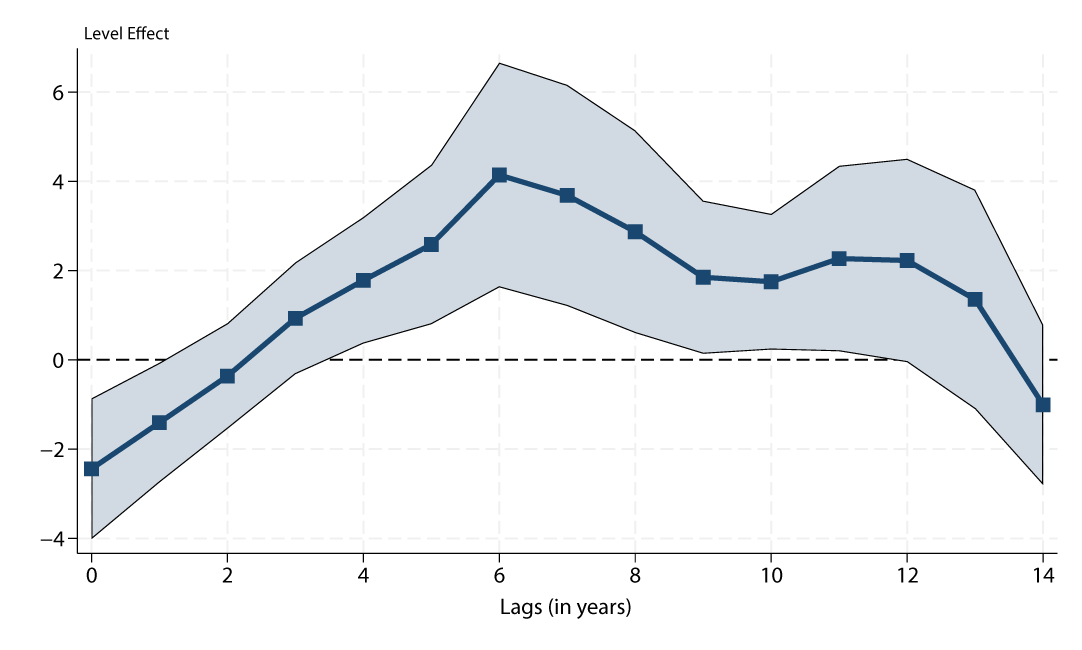

Figure 3 tests the relevance of the IV strategy. To construct a measure of import exposure at the sector level, I rely on the pre-2000 average employment shares across sectors; the underlying assumption for this instrument is that technological diffusion—reflected in rising imports of computer and communication equipment—occurs more rapidly in historically larger sectors, as they may be more likely to adopt and integrate high-tech tools at scale. In the Figure, the blue markers denote the estimated effect of world (ex U.S.) imports of computers and communication equipment on remote ability over several years; these estimates exploit the variation in import exposure within sectors over time.6 As before, the blue shaded area represent the 95 percent confidence interval. Notably, higher imports of high-tech products by countries other than the U.S. are associated with a decline in U.S. remote ability on impact, possibly reflecting short-run supply constraints. Indeed, stronger foreign demand for high-tech goods may reduce their availability in the U.S. market in the short run, crowding out domestic consumption and potentially damping short-term remote work ability. At further time horizons, instead, an increase in foreign imports of high-tech goods eventually expands the share of employment in remote-ready occupations, with an effect that peaks at the six-year mark. These lagged effects may be attributed to a combination of increased supply elasticity over time and the gradual nature of technological diffusion and integration within firms and industries.

Notes: Point estimates of the effect of world (excluding U.S.) imports of computers and communication equipment on remote ability, controlling for year- and 4-digit NAICS fixed effects. Shaded area denotes 95 percent confidence interval.

Source: BLS, World Bank, and USDOL/ETA.

With the first-stage relationship empirically validated, I proceed by instrumenting remote work ability with lagged values of foreign imports of computer and communication equipment. Based on the empirical patterns documented above, I rely on a six-year lag relationship between the instrument and the main control variable.

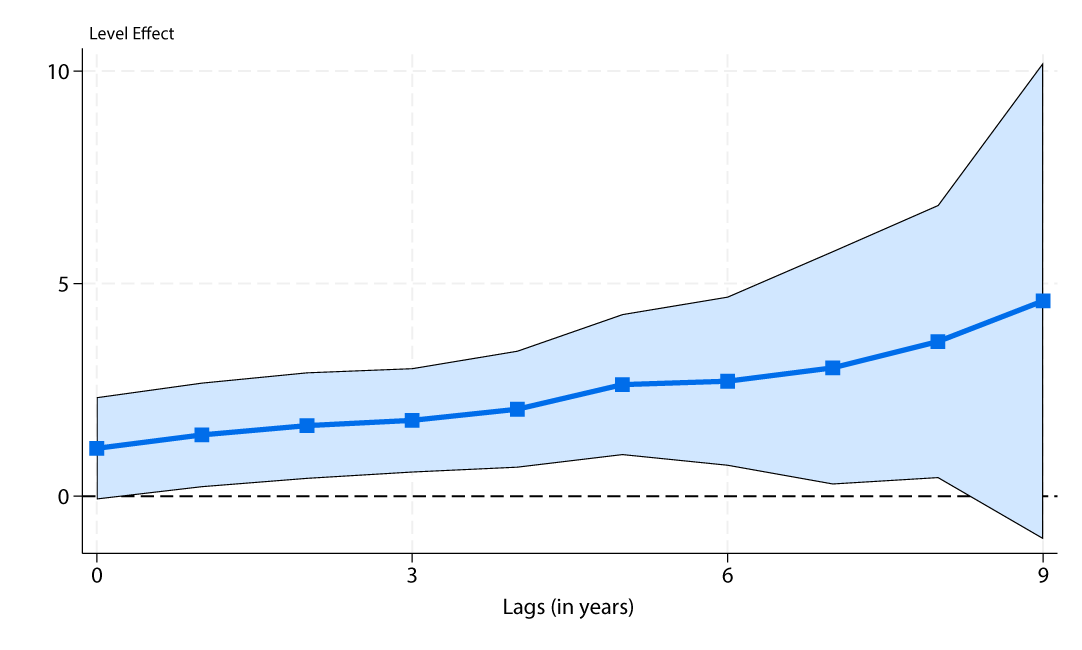

The IV estimates, summarized in Figure 4, continue to show a consistently positive relationship between remote ability and labor productivity; the results for multifactor productivity (not shown) are, instead, very imprecisely estimated. The point estimates remain relatively stable across all lags of remote ability but become increasingly imprecise and not significant beyond eight lags, as the extended lag structure materially reduces the available sample size. More importantly, the coefficient estimates—indicated by the blue markers in Figure 4—are roughly an order of magnitude larger than those from the baseline model (shown in Figure 1). This difference may reflect measurement error or selection dynamics, where increases in remote work ability are more likely to occur in less productive sectors as a strategy to enhance the attractiveness of jobs in those sectors. The implied magnitudes are striking: a one standard deviation increase in remote ability is associated with a more than two standard deviation rise in productivity after three years.

Notes: Point estimates of the effect of remote ability, instrumented with world ex U.S. imports of computers and communication equipment, on labor productivity, controlling for year- and 4-digit NAICS fixed effects. Shaded area denotes 95 percent confidence interval.

Source: BLS, World Bank, and USDOL/ETA.

To better understand the significance of these estimates, let's place them in historical context by comparing recent trends in remote ability and productivity. In the post-pandemic period, remote work ability increased by approximately 5 percentage points relative to the pre-pandemic baseline. According to the IV estimates, this rise in remote ability would predict an increase in labor productivity of about 8 index points over the following three years. So far, the available data indicate that actual labor productivity rose by 5 index points between 2019 and 2022. Given the substantial lags identified in the empirical analysis, it is likely that part of the productivity gains linked to the shift toward remote work have yet to materialize.

In conclusion, this note offers a novel perspective on the relationship between remote work and productivity by focusing on the inherent ability to work remotely rather than actual remote work adoption. Using task-based measures and an instrumental variable (IV) strategy, I find that increases in remote work ability led to sizable productivity gains over time. Crucially, these gains materialize gradually, highlighting the importance of adopting a long-term perspective when evaluating remote work policies and investments, as the full productivity benefits may not be immediately apparent but could be substantial over time.

References

Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying (2015). "Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment," Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 130 (February), pp. 165–218.

Choudhury, Prithwiraj (Raj), Cirrus Foroughi, and Barbara Larson (2021). "Work-from-Anywhere: The Productivity Effects of Geographic Flexibility," Strategic Management Journal, vol. 42 (April), pp. 655–83.

DeFilippis, Evan, Stephen Michael Impink, Madison Singell, Jeffrey T. Polzer, and Raffaella Sadun (2020). "Collaborating during Coronavirus: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Nature of Work," NBER Working Paper Series 27612. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, July, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27612.

Emanuel, Natalia, and Emma Harrington (2024). "Working Remotely? Selection, Treatment, and the Market for Remote Work," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 16 (October), pp. 528–59.

Langemeier, Kathryn, and Maria D. Tito (2022). "The Ability to Work Remotely: Measures and Implications," Review of Economic Analysis, vol. 14 (2), pp. 319–33.

Montenovo, Laura, Xuan Jiang, Felipe Lozano Rojas, Ian M. Schmutte, Kosali I. Simon, Bruce A. Weinberg, and Coady Wing (2020). "Determinants of Disparities in COVID-19 Job Losses," NBER Working Paper Series 27132. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, May (revised June 2021), https://www.nber.org/papers/w27132.

Morikawa, Masayuki (2020). "Productivity of Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from an Employee Survey," Covid Economics, vol. 49, pp. 123–39.

Yang, Longqi, David Holtz, Sonia Jaffe, Siddharth Suri, Shilpi Sinha, Jeffrey Weston, Connor Joyce, Neha Shah, Kevin Sherman, Brent Hecht, and Jaime Teevan (2022). "The Effects of Remote Work on Collaboration among Information Workers," Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 6, pp. 43–54.

1. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. See, for example, Bloom and others (2015) and Choudhury, Foroughi, and Larson (2021). Return to text

3. See, among others, DeFilippis and others (2020), Morikawa (2020), and Yang and others (2022). Return to text

4. Indeed, Emanuel and Harrington (2024) find that while remote workers were, on average, more productive than in-office workers, this difference was largely driven by the selection of more productive workers into remote jobs. When controlling for selection, the authors document a causal effect of remote work on productivity close to zero. Return to text

5. For more details, see Langemeier and Tito (2022). Return to text

6. As in our baseline model, I control for sector and time fixed effects. Return to text

Tito, Maria D. (2025). "Decoding the Productivity Puzzle: A New Perspective on the Relationship between Remote Work and Productivity," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August 25, 20255, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3890.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.