FEDS Notes

January 17, 2025

Developments in Chinese Chipmaking

Colin Caines, Sharon Jeon, and Cheyenne Quijano

Introduction

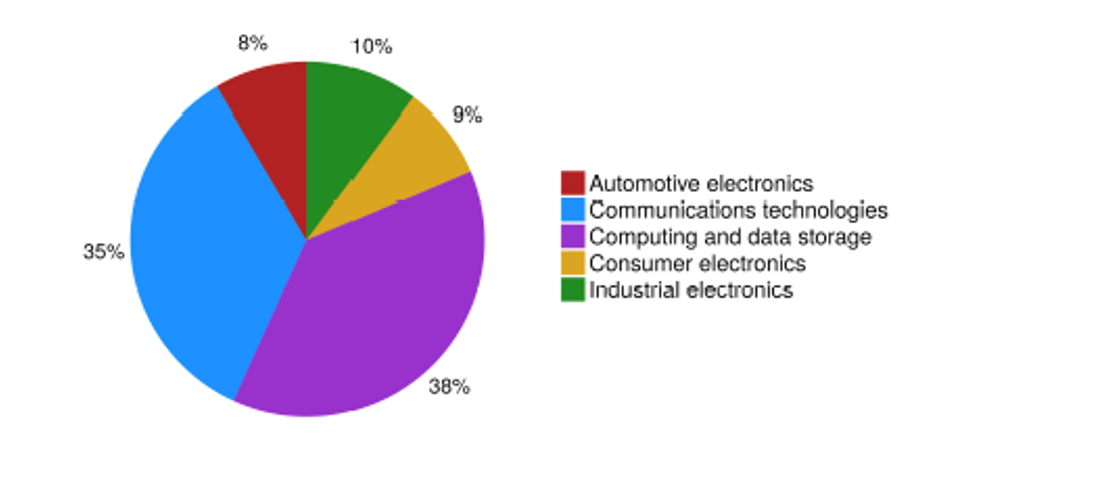

The global semiconductor industry has become a key source of global economic and geopolitical risks. Due to a combination of huge fixed costs, highly specialized human capital, and a high degree of geographic concentration at different stages of production, chipmaking exhibits extremely low substitutability throughout the value chain. Consequently, the industry is vulnerable to supply chain shocks, which, given the role of semiconductors as a necessary input to a huge array of manufactured goods (figure 1), can have large and persistent global effects. Moreover, chips are also viewed as crucial to developing frontier technologies such as artificial intelligence and are increasingly critical to national security.

Rising trade tensions and an increasing turn to industrial policy planning have led major economies to increase investments in their domestic chipmaking. In particular, both China and the United States have made substantial commitments to developing a reliable supply of domestically-sourced chips. In light of these developments, this note discusses the prospects for China's strategy to expand its footprint in global chipmaking.

Note: The data are for 2021. Legend entries appear in counterclockwise chart order.

Source: McKinsey & Company.

Chip manufacturing in brief

To highlight the complexity and vulnerability of this industry, we begin with an overview of the chip production process. Modern semiconductor manufacturing is characterized by an astounding degree of miniaturization. Individual components such as transistors, which with current technology can be less than one ten-thousandth the size of a human hair, are patterned onto silicon via a process called ultraviolet photolithography. These components are connected by submicroscopic wiring in order to form complete integrated circuits, or chips, each of which can contain tens of billions of transistors and hundreds of kilometers of wiring. Multiple such chips are formed on circular silicon wafers, from which they are cut and packaged to be used in electronic devices.

The complexity of this production process is commonly characterized by the geometry or process "node", which, broadly speaking, describes the size of individual features of transistors. As transistors have become smaller, the density of components on individual chips, and therefore their processing power, has increased. Consequently, cutting-edge chips, roughly those classified at 5 nanometers (nm) and below, are heavily demanded by frontier sectors such as artificial intelligence. While cutting-edge chip production has been the focus of much commentary of late, it should be noted that chips produced at legacy nodes (classified at 28 nm or above by the 2022 U.S. CHIPS and Science Act) retain huge economic and strategic importance, given their widespread use in automobiles, aircraft, household appliances, and defense applications.

Most semiconductors are produced through a foundry process whereby chip design is separated from the physical fabrication of chips. U.S. and Korean firms are dominant in the former process, while the latter is dominated by firms in the Indo-pacific, particularly Taiwan. Meanwhile, the back-end assembly and testing of chips largely takes place in Southeast Asia. A characteristic of this process is that, for a number of reasons, there is limited scope for substitution at different stages of the value chain. First, the supply of raw material inputs tend to display heavy geographic concentration. For example, over 80 percent of processed rare earth elements come from China. Second, research and development costs are extremely high, both in the design of chips, where the cost of designing a new 2 nm chips is now estimated to be over $700 million, and in the production of chipmaking equipment, leading to heavy concentration in some segments of the equipment market. For example, a single Dutch company, ASML, has 100 percent market share for the most advanced lithography machines needed to produce cutting-edge chips. Finally, human capital is highly specialized throughout the value chain. The fact that there is very limited scope for substitution at each stage of the chip supply chain, combined with some critical geographic choke points implies that global chip supply is sensitive to geopolitical developments. The most salient risk arises from possible conflicts in Taiwan, and countries with dominant positions in the supply chain can wield economic and strategic power.

China's industrial policy

In recent years, China has made substantial commitments to upgrading its manufacturing sector. In particular, China's Made in China 2025 plan set the goal of achieving a high degree of self-sufficiency across a range of frontier sectors, including information technology, robotics, and new energy vehicles. More recently, the authorities' China Standards 2023 initiative aims to position Chinese industry at the forefront of developing global standards in emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence. China's emerging industrial policy appears to be motivated by a desire to: first, make its supply chains resilient to geopolitical risks; second, bolster national security by limiting the degree of foreign technology used in critical infrastructure and defense equipment; third, become a leader in frontier technologies that might drive future productivity gains; and finally, to capture foreign markets in frontier sectors as part of an export-led growth strategy. Fundamental to achieving these goals is the need for China to develop a domestic chipmaking sector.

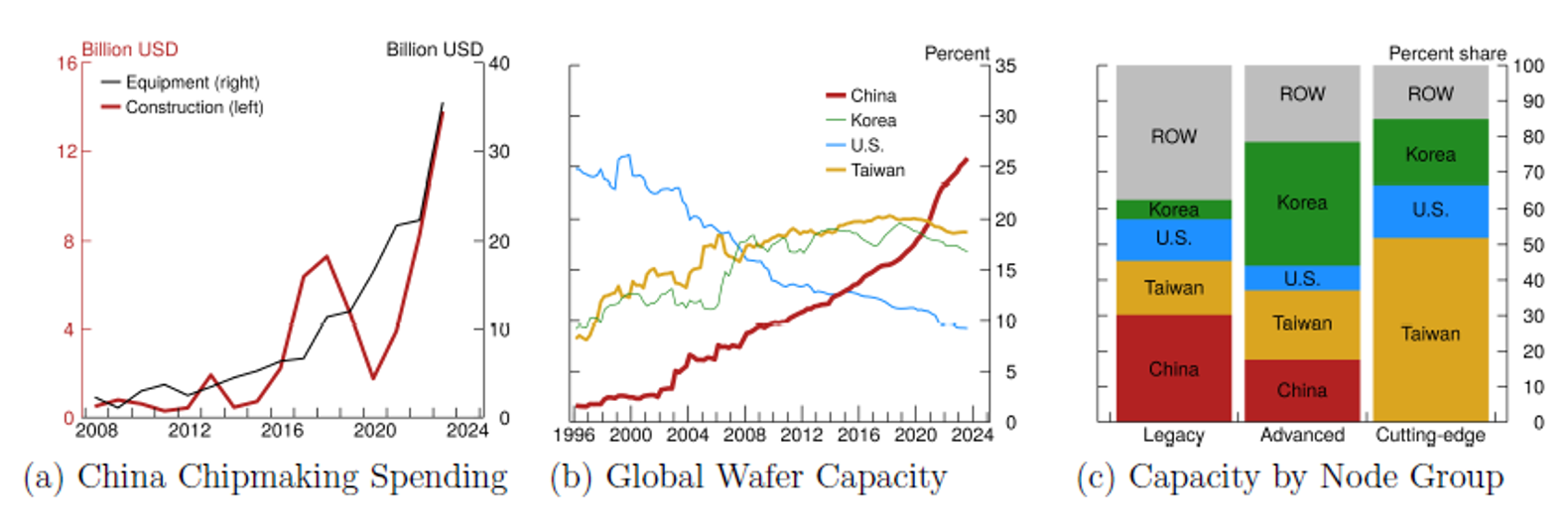

As can be seen in panel (a) of figure 2, Chinese expenditures on both chip plant construction and chipmaking equipment have accelerated rapidly, supported by investments from large state-led investment funds, such as the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, and generous government subsidies. As a result, as can be seen in panel (b), China's chipmaking capacity, as measured by the number of 8-inch wafers that can be processed by its fabrication plants, has increased dramatically and it is now the global leader. However, Chinese production remains heavily concentrated in legacy chips. As seen in panel (c), China has essentially no production capacity for high-end chips, a market segment dominated by firms in Taiwan, Korea, and the U.S.

(a) China Chipmaking Spending

Note: The data extend through 2023.

Source: SEMI World Fab Forecast; authors’ calculations.

(b) Global Wafer Capacity

Note: Capacity in other sizes is standardized to the equivalent of an 8-inch wafer. The data prior to 2008 from Gartner. The data extend through 2023:Q3.

Source: SEMI World Fab Forecast; Gartner; authors’ calculations.

(c) Capacity by Node Group

Note: Legacy nodes are 28 nm and above, advanced nodes are 6 to 27 nm, and cutting-edge nodes are 5 nm and below. Global production share of legacy nodes is 69%, advanced nodes is 37%, and cutting-edge nodes is 4%. The data are for 2023:Q3 and by country of production.

Source: SEMI World Fab Forecast; authors’ calculations.

Impact of trade and investment restrictions on Chinese capacity

In recent years, many countries, including the U.S., have taken steps to reduce vulnerabilities. First, through the CHIPS Act, the U.S. is incentivizing domestic chipmaking capacity. In addition, U.S. policymakers have tried to limit China's access to high-end chips, which are viewed as an increasing national security concern. In 2018, the U.S. began intensifying sanctions on Chinese tech firms, a process that culminated in an October 2022 Executive Order that imposed broad licensing requirements on U.S. exports to Chinese AI, computing, and chipmaking entities; restricted the sale of both U.S.-produced chips and chips produced abroad using U.S. intellectual property; and imposed end-use controls on exports of chipmaking tools.

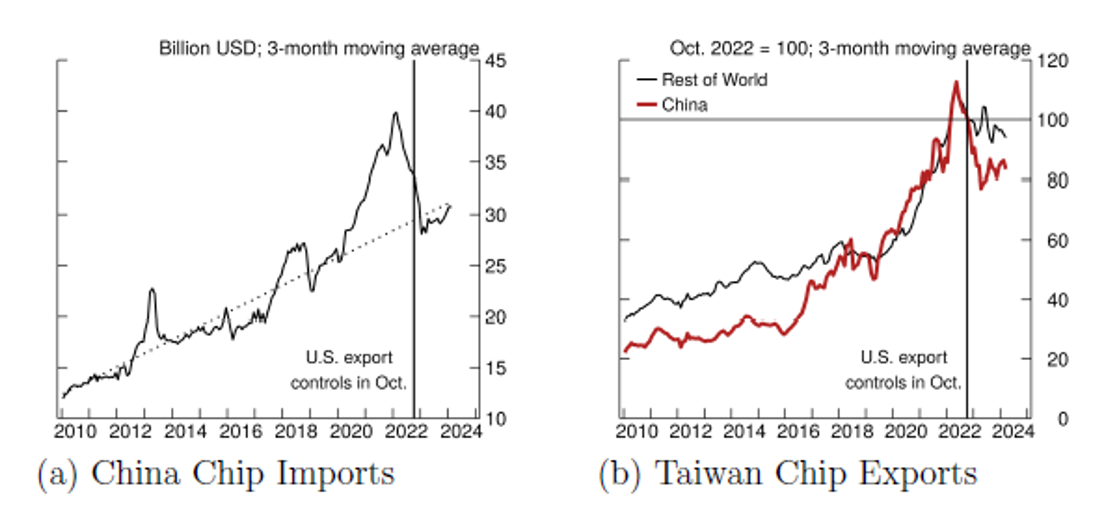

As can be seen in panel (a) of figure 3 China's total chip imports fell notably after sanctions were imposed. However, this was likely due in part to cyclical factors, as the sanctions coincided with the pandemic goods boom fading. While Taiwan's exports of chips to China fell significantly more than its exports of chips to the rest of the world (panel (b)), suggesting some impact from U.S. sanctions, it should be noted that China's overall chip imports are still running about in line with its pre-pandemic trend. This is because U.S. sanctions have left China's access to legacy chips, which comprise the bulk of Chinese chip imports, largely unaffected.

(a) China Chip Imports

Note: The data extend through February 2024. The dotted line shows pre-pandemic trend line. Vertical line indicates U.S. export controls in October 2022.

Source: Haver Analytics; authors’ calculations.

(b) Taiwan Chip Exports

Note: The data extend through February 2024. Vertical line indicates U.S. export controls in October 2022.

Source: Haver Analytics; authors’ calculations.

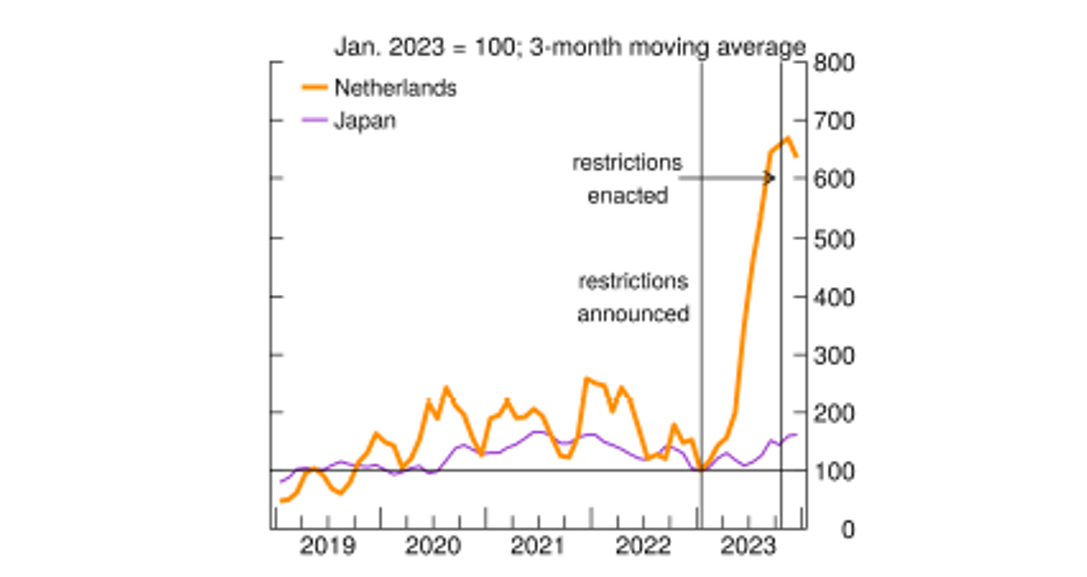

Instead, U.S. efforts have focused on limiting China's access to high-end chips. In addition to prohibiting the export of several classes of high-end chips to China the U.S has moved to limit China's access to chipmaking equipment that could be used to produce comparable technology domestically. Furthermore, in 2023, the U.S. convinced both Japan and the Netherlands to restrict exports of chipmaking equipment to China. Notably, the Netherlands agreed to stop the sale of the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) photolithography machines, which are necessary for producing below 5 nm and in which it holds a 100 percent global market share. Evidence of sanctions front-running is apparent from nearly sevenfold increase in China's imports of chipmaking equipment from the Netherlands between the announcement and imposition of restrictions (figure 4), underscoring the risk these measures posed to the Chinese industry.

Note: The data extend through December 2023. First vertical line indicates restrictions announced in January 2023, second vertical line indicates restrictions enacted on October 2023.

Source: UN Comtrade; authors’ calculations.

Conclusion

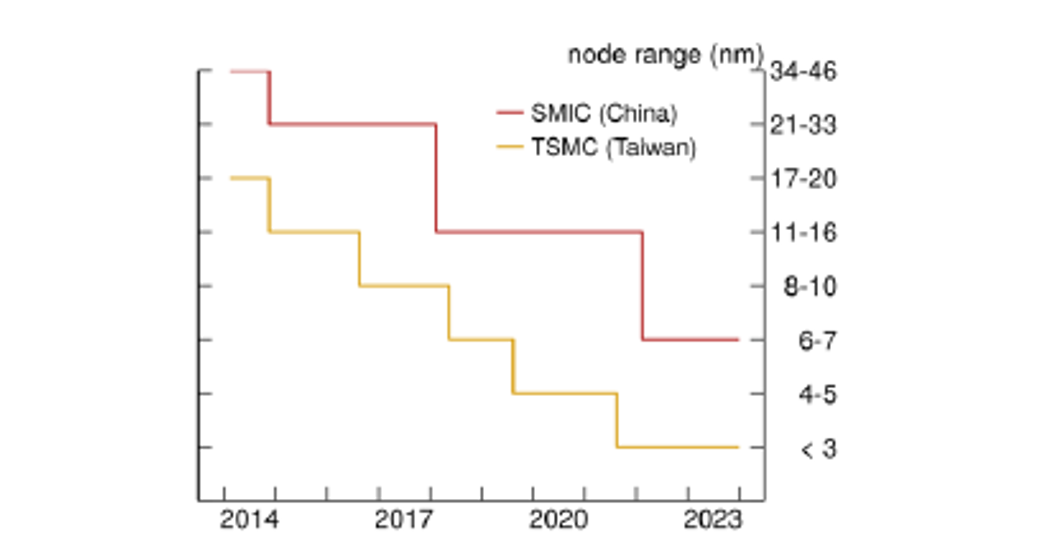

Will recent actions impose significant setbacks to China's chipmakers? One view is that restrictions on China's access to chipmaking equipment could meaningfully set back its development of cutting-edge chips, with downstream effects on sectors that use this technology. Replicating EUV lithography equipment is widely considered infeasible in the short- to medium-run, given the high levels of specific human capital embodied by this technology. Moreover, small sales volumes of these machines make sanctions evasion difficult, as it is relatively easy to track end-use. Given that Chinese chip producers are already behind a constantly moving frontier (figure 5) these restrictions could further widen the gap.

That said, Chinese firms have demonstrated a notable capacity for innovation. For example, China's chipmaking giant Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), recently defied expectations by announcing it could produce chips at the 5 nm node. Moreover, while U.S. restrictions on high-end chips impose significant costs on Chinese industry, China heavily subsidizes its national champions.

Note: Units are adjusted to 8-inch wafers per month.

Source: SEMI World Fab Forecast; authors' calculations.

References

Allen, G. C., 2023. China's New Strategy for Waging the Microchip Tech War. Center for Strategic & International Studies.

Burkacky, O., Dragon, J., Lehmann, N., 2022. The semiconductor decade: A trillion-dollar industry. McKinsey & Company.

Chapman, B., 2024. Recent U.S. government and foreign national government and commercial literature on semiconductors. Journal of Business and Finance Librarianship.

Lee, J., Kleinhans, J.-P., 2021. Mapping China's semiconductor ecosystem in global context:

Strategic dimensions and conclusions. Mercator Institute for China Studies. Policy Brief.

Semiconductor Industry Association, 2021. Taking stock of China's semiconductor industry.

Shivakumar, S., Wessner, C., Thomas, H., 2023. The Strategic Importance of Legacy Chips. Center for Strategic & International Studies.

Shivakumar, S., Wessner, C., Thomas, H., 2024. Balancing the Ledger: Export Controls on U.S. Chip Technology to China. Center for Strategic & International Studies.

Thadani, A., Allen, G. C., 2023. Mapping the Semiconductor Supply China. CSIS briefs, Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Triolo, P., 2024. A new era for the Chinese semiconductor industry: Beijing responds to export controls. American Affairs.

Caines, Colin, Sharon Jeon, and Cheyenne Quijano (2025). "Developments in Chinese Chipmaking," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 17, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3647.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.