FEDS Notes

December 17, 2025

In the Shadow of Bank Runs: Lessons from the Silicon Valley Bank Failure and Its Impact on Stablecoins

Chuan Du, Ria Sonawane, and Cy Watsky

Summary

Stablecoins are crypto-assets designed to maintain a stable value against a reference asset, typically the U.S. Dollar. The peg to the dollar is supported by the assets that back the stablecoin. Stablecoins perform dollar-like functions in decentralized finance ("DeFi") and represent a run-able liability for their issuers. As with money market funds and bank deposits, stablecoins are susceptible to crises of confidence, contagion, and self-reinforcing runs.

In this note we utilize a granular dataset to document the market stress experienced by USDC, the second largest stablecoin by market cap, during the Silicon Valley Bank ("SVB") crisis of March 2023. SVB was a traditional bank that failed due to inadequate risk management practices.1 The bank experienced a rapid run of deposits and was taken into receivership by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ("FDIC").

Shortly after, Circle, the issuer of USDC, publicly announced that it was unable to access a portion of its dollar reserves held as (uninsured) deposits at SVB. This announcement precipitated a surge in redemption requests by holders of USDC, causing the stablecoin to lose its peg against the dollar on secondary markets when Circle shut down primary market operations over the weekend.

We identify a key channel of contagion in the DeFi sector, illustrative of the potential for code-based financial products to amplify stress. At the same time during the resolution of SVB, a crypto-collateralized stablecoin, Dai, was operating one-to-one exchange facilities — called Peg Stability Modules ("PSMs") — against USDC and other stablecoins.2 Over the weekend, these PSMs were rapidly drained of liquidity. Dai, and other stablecoins with otherwise no exposure to SVB, also lost their peg to the dollar. Both the SVB run and the stablecoins depegs were ameliorated when the FDIC, the Treasury Department, and the Federal Reserve Board jointly announced that all depositors in SVB would be fully protected.

We highlight three aspects of this USDC depeg episode.

First, there is a potential for two-way feedback between the traditional and the DeFi sectors. In this event, the run on SVB was the trigger for the USDC depeg, which then sparked a broader sell-off in other stablecoins. Intervention designed to backstop SVB stemmed the selling pressure on the affected stablecoins while the USDC primary market was closed. But had the run unfolded differently, the pressure for USDC redemptions might have forced Circle to liquidate backing assets (for example, U.S.Treasury securities), with potential knock-on effects on traditional financial markets.

Second, while stablecoins with high quality backing assets can maintain their pegs during normal times, they may still be fragile during periods of significant stress. When stablecoins lose their peg against the dollar, the effect can reverberate through the sector.

Third, smart contracts, such as the one-to-one exchange facilities backing Dai, can create interlinkages between DeFi participants. Such facilities can be created at the discretion of any individual participant and operate autonomously. Without appropriate consideration of the risks posed to the wider ecosystem, these interlinkages can channel and amplify contagion.

This paper provides a detailed account of how SVB's failure affected USDC and other stablecoins during March 2023. Our account is backed by granular data on both the primary and secondary market activities of the affected stablecoins.

Policy discussions relating to the design of stablecoin regulations are outside of the scope of our study.

Future research should explore relevant counterfactuals and other instances of pressure in stablecoin markets to better understand how the traditional and DeFi markets interact during periods of significant stress. Further studies are particularly important as stablecoins continue to expand their role in the economy.

1. The Run on SVB and its implications for USDC

On the morning of Friday, March 10, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank ("SVB") entered bank resolution after experiencing over $40 billion in withdrawals from depositors in a single day.3 At 10 p.m. on Friday evening, Circle announced that it was unable to withdraw $3.3 billion of USDC reserves from SVB (around 8% of total reserves at the time), sparking a wave of redemption requests for the stablecoin.4

Solvency concerns around Circle are likely to have played a part. As a private company at the time, Circle was not subject to public disclosure requirements; however, subsequent filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission on April 1, 2025, stated that Circle's total stockholders' equity as of December 31, 2023, was $0.34 billion, representing just over a tenth of the $3.3 billion reserves held at SVB.5* Without a public guarantee on the uninsured deposits at SVB, Circle faced the possibility of a significant shortfall.

Solvency concerns can morph and extend into liquidity concerns. Redemption requests in the primary market for USDC rose sharply after the announcement that SVB was taken into receivership, ahead of Circle's public acknowledgment that it was unable to access deposits at SVB. Suspension of primary market redemptions over the ensuing weekend contributed to selling pressure on USDC in the secondary markets, triggering a depeg against the U.S. dollar in the secondary market. Public reassurances from Circle that it would "stand behind USDC and cover any shortfall using corporate resources, involving external capital if necessary," may have helped to shore up the price of USDC during the weekend, but were not sufficient to restore the peg.6

1.1 Primary Market Shutdown

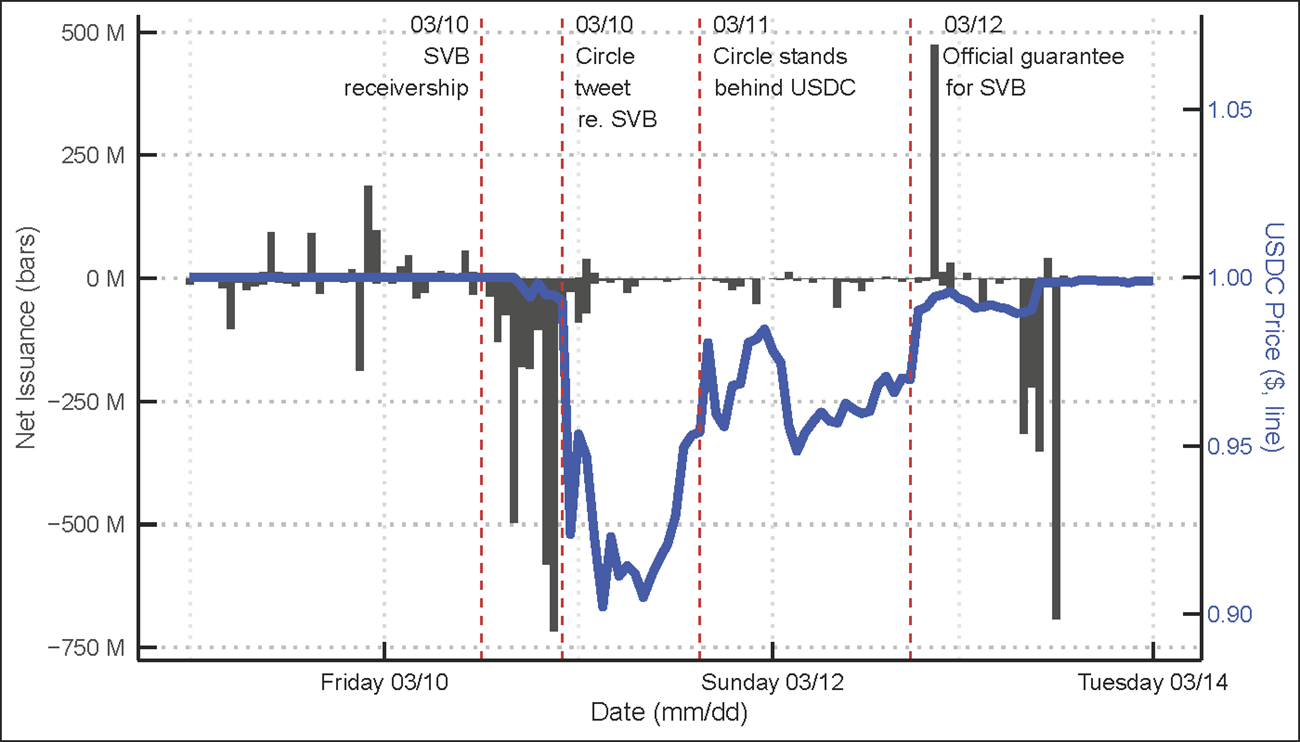

Our granular dataset allows us to analyze the market dynamics during the SVB episode in great detail.7 Figure 1 tracks the hourly net issuance of USDC on its primary market (bars), overlaid on top of the secondary market price of USDC (line), from Thursday, March 9 to Tuesday, March 14, 2023. Event lines indicate the timing of major public announcements related to the episode.

Source: Allium, CryptoCompare.

The bars indicate significant USDC redemptions after SVB was taken into receivership at 11:37 a.m. ET on Friday, March 10, even before Circle's public announcement around 10 p.m. that same day. Redemptions peaked shortly before this announcement, then dropped to minimal levels over the weekend, as Circle announced that issuance and redemptions were "constrained by working hours of the U.S. banking systems."8

The selloffs translated into a dramatic depeg when Circle publicly tweeted about its exposure to SVB and the primary market largely ceased operations (as shown by the line). At its trough, USDC traded at 86 cents to the dollar.9 Public commitment from Circle, to stand behind USDC using "external capital," on Saturday, March 11 provided price support but did not restore the peg.

The "resolution weekend" for SVB culminated in a joint press release by the Department of the Treasury, the Federal Reserve Board, and the FDIC at 6:15 p.m. ET, Sunday, March 12, 2023. The press release announced that the Federal Reserve "will make available additional funding to eligible depository institutions to help assure banks have the ability to meet the needs of all their (insured and uninsured) depositors." USDC's price on the secondary market recovered sharply after the backstop announcement on Sunday and fully recovered once Circle began processing redemptions on Monday, March 13.

On Wednesday, March 15 Circle announced: "we have cleared substantially all of the backlog of minting and redemption requests for USDC" and "continue making progress toward full USDC liquidity operations [...] Since Monday morning, Circle has redeemed $3.8 billion in USDC and minted $0.8 billion USDC."10

The timing of both primary market redemptions and secondary market price dislocation confirm predictable but insightful facts about stablecoin markets.11 First, traders responded rapidly to news about SVB, and redemptions increased quickly following this information. Second, primary market activity clearly mattered for USDC's price on secondary markets. It wasn't until primary markets shut down that USDC's hit its low point, and it wasn't until Circle began processing redemptions again that USDC returned to its peg. Third, information asymmetry may have played a role. Some (possibly more informed) traders ran ahead of Circle's own announcement on Friday, while others followed afterwards.

1.2 Secondary Market Activity

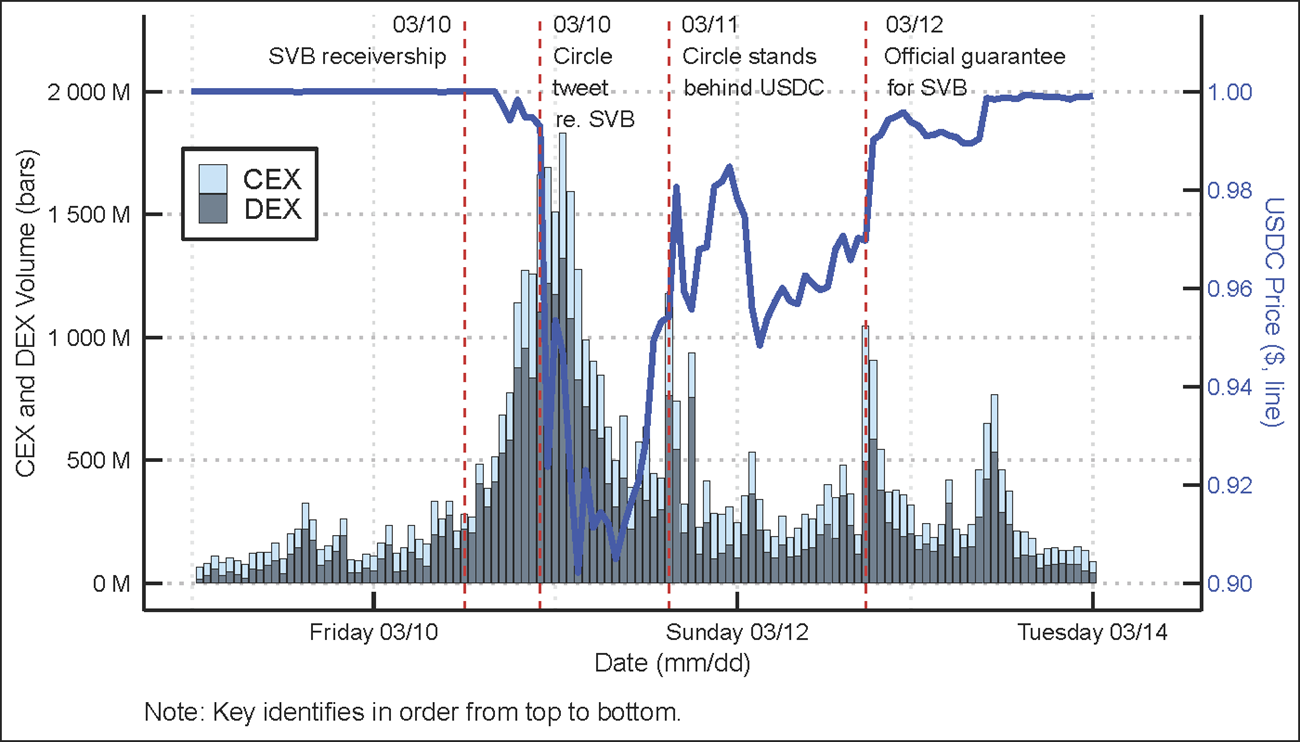

Unlike bank deposits, stablecoins are actively traded on exchanges in the secondary markets. This means that the suspension of redemption on the primary market cannot arrest a run, as temporarily closing a bank would. USDC trading activity on its secondary market during the resolution weekend offers an additional window into the potential dynamics of a stablecoin run.12

Trading volumes on the secondary markets for USDC were highly elevated throughout the episode – especially during the suspension of the primary market. Pent up redemption pressure was reflected in a surge of trading on centralized and decentralized exchanges. Hourly trading volume shot up to nearly $2 billion on March 11, triggering the sharp price dislocation of USDC against the dollar.

Figure 2 plots the trading volume of USDC on the secondary markets, decomposed into activity on decentralized exchanges (“DEXs”) and centralized exchanges (“CEXs”). Though centralized exchanges tend to handle a higher volume of crypto-asset trading activity than decentralized exchanges during normal times; during the crisis, trading on DEXs rose dramatically and accounted for most of the activity.13

Source: CryptoCompare.

As we see in Figure 2, trading volumes on secondary markets also increased in the run up to Circle's Friday announcement, mirroring the primary market trend. This suggests some traders were sensitive towards potential issues with respect to USDC and began exiting USDC positions in advance of the public announcement.

2. The contagion to Dai: A DeFi transmission channel

Like bank runs, stress originating in one stablecoin can spillover to other industry participants. Such contagion can be direct, for example, through explicit interlinkages, or indirect, for example, through a crisis of confidence. Most episodes exhibit elements of both.

We highlight the direct contagion from USDC to a crypto-backed “stablecoin", Dai.14 The issuer of Dai, MakerDAO, operates a set of smart-contract-based collateralized lending facilities issuing Dai tokens in return for crypto collateral.15 One such facility, named the Dai-USDC Peg Stability Module ("USDC-PSM"), allowed users to exchange between Dai and USDC on a one-to-one basis, and was designed to stabilize Dai's price at one dollar by explicitly pegging Dai to USDC. While this mechanism worked in normal times, during the SVB crisis the PSM became an escape valve for USDC holders and triggered simultaneous selling pressures on both stablecoins.

2.1 Escaping through the USDC-PSM

As Circle halted its primary market transactions over the resolution weekend, and exchanges stopped accepting USDC at par, the USDC-PSM became an attractive way for traders to exit their USDC positions.16 The PSM's hard-coded smart contracts continued to accept USDC on a one-for-one basis against Dai. The only safeguard was a 950 million USDC daily cap built into the facility.

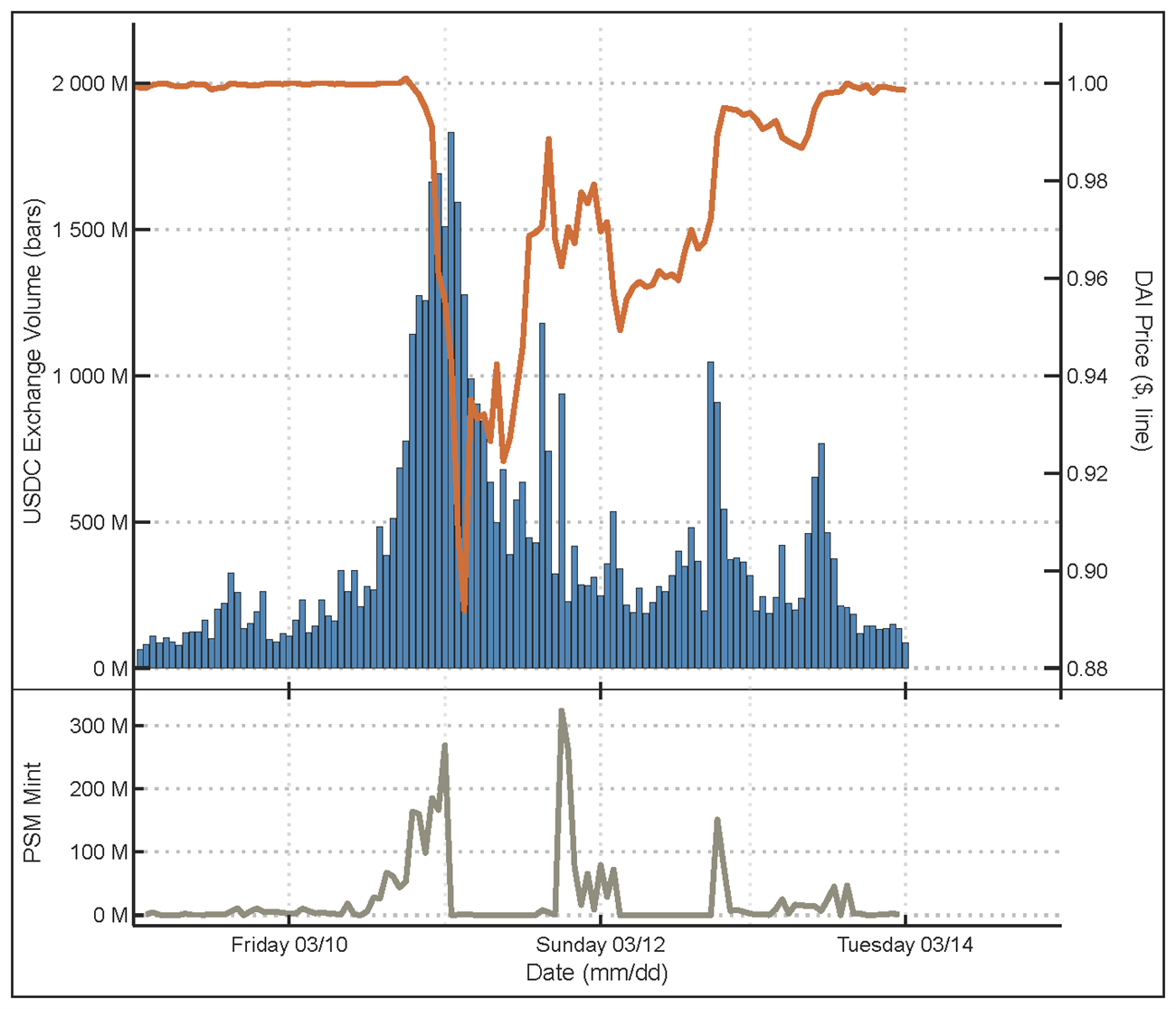

As the bottom panel of Figure 3 illustrates, the volume of minting activity in the PSM shot up on Friday, March 10, and the 950 million daily cap was swiftly reached. Activity in the PSM strongly correlated with the increase in USDC trading volumes on exchanges in the run-up to Circle's announcement, reflecting the fact that the PSM was well integrated into secondary markets. Many centralized and decentralized exchanges used automated processes to search for the most favorable price for those seeking to exit USDC positions.

Source: Allium, CryptoCompare.

Trading through the PSM resumed on Saturday, March 11, but quickly shut down again once the daily cap was reached.

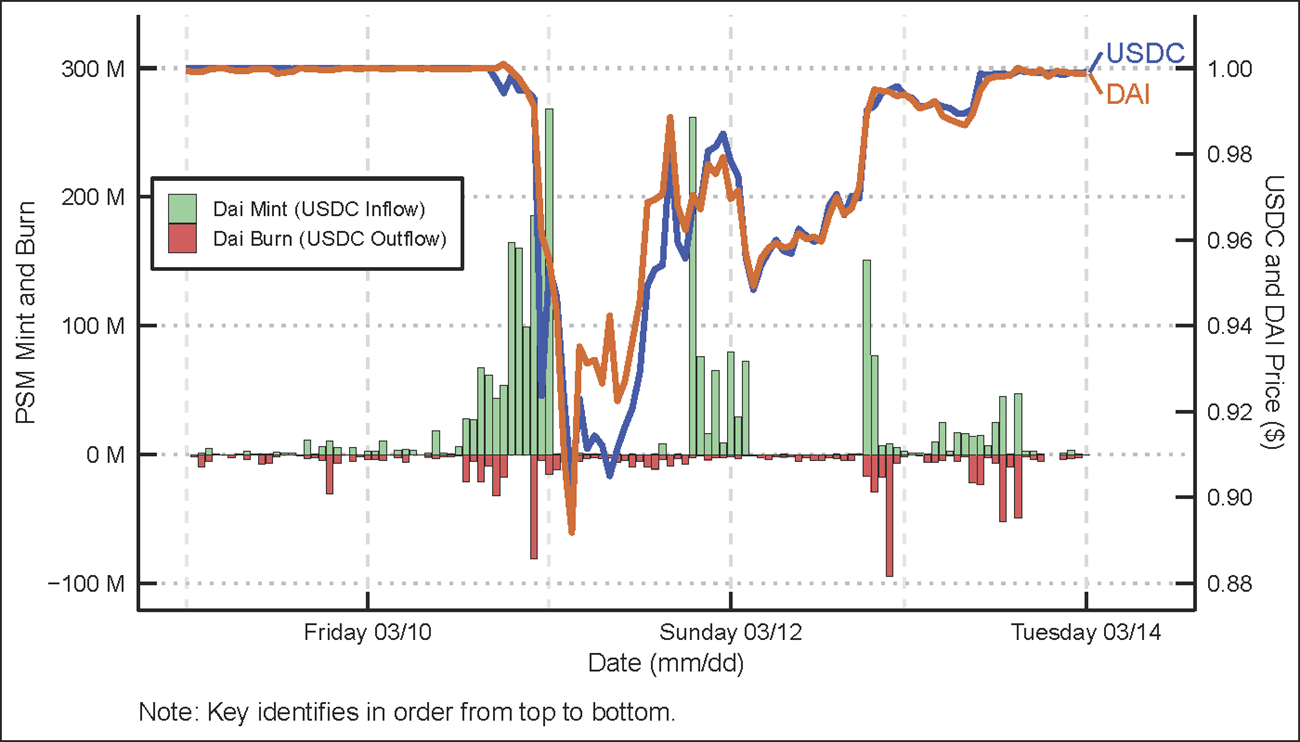

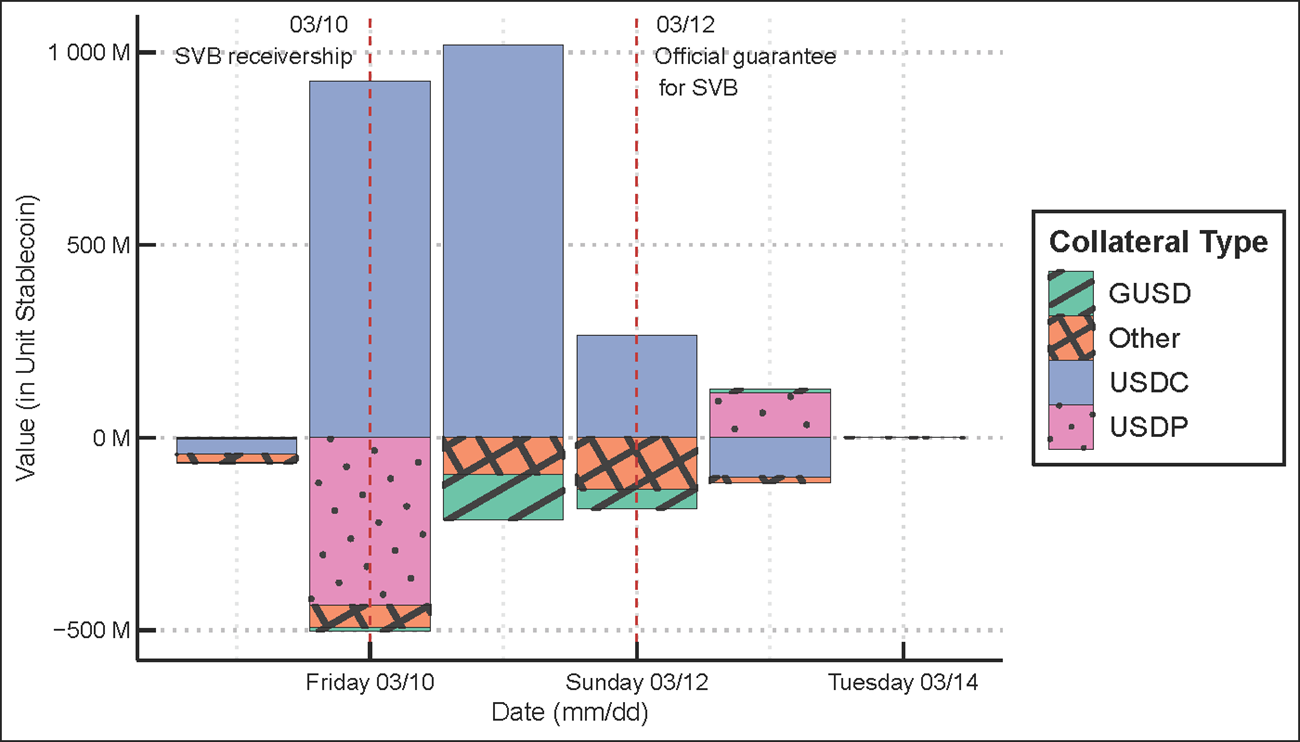

Figure 4 plots PSM activity against secondary prices of USDC and Dai. Positive bars represent USDC being deposited in the PSM (traders selling USDC for newly minted Dai), and negative bars represent USDC being withdrawn from the PSM (traders burning Dai for USDC).

Source: Allium, CryptoCompare.

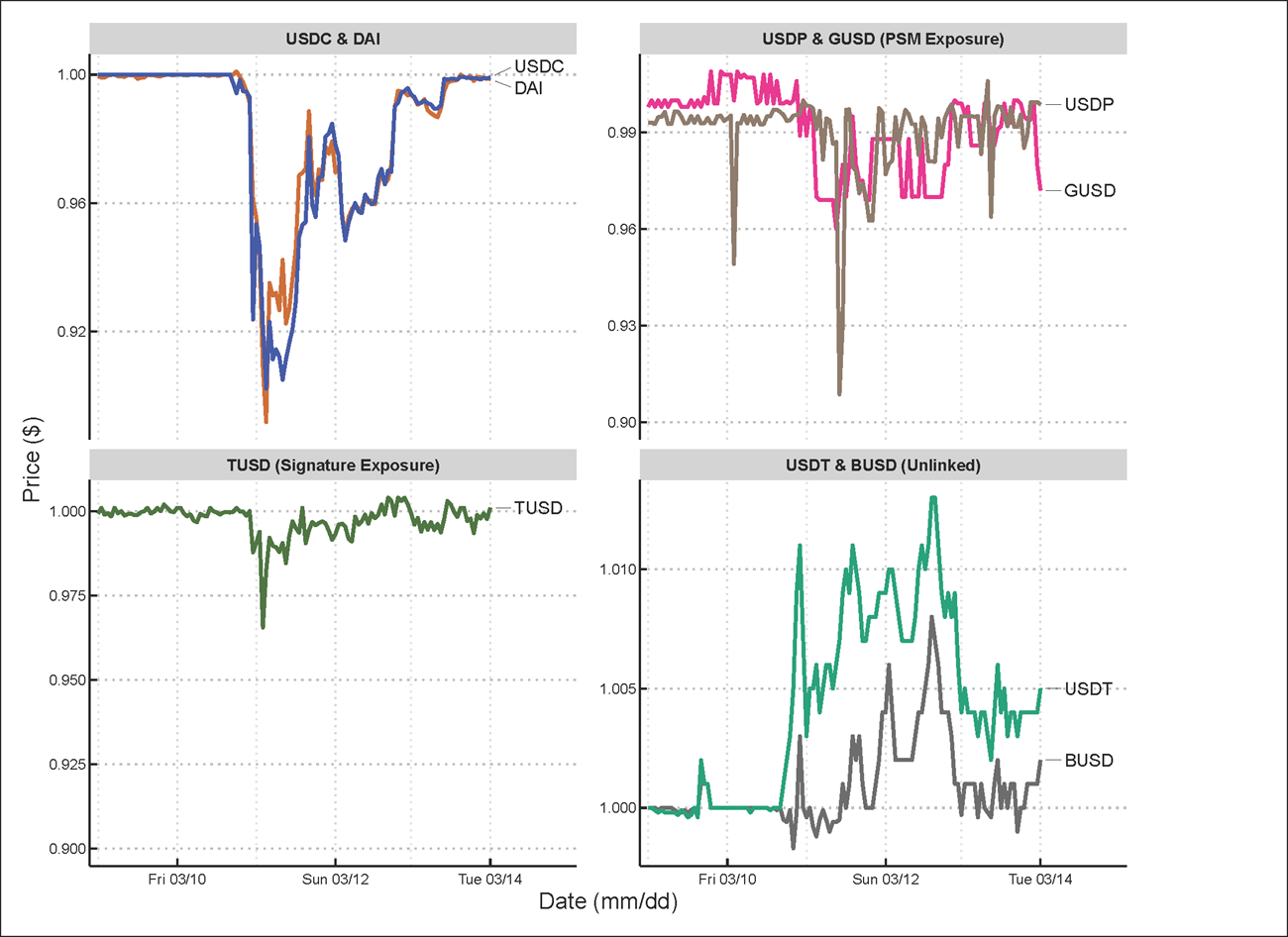

As expected, the price of both USDC and Dai fell in tandem in the window when the PSM was operational. Once the PSM daily cap was reached, however, a price differential opened up on March 11, with USDC falling further as selling continued through other channels. Prices converged once again upon the resumption of the PSM and remained broadly in lockstep thereafter.

The presence of the PSM helped to relieve some of the selling pressure on USDC. The PSM provided a hard-coded, zero-haircut facility offering Dai "at par" against USDC. The fact that the PSM was used up to its daily limit until the announcement of the Fed backstop suggests that the price drop for USDC would have been even more stark in its absence.

2.2 The Peg Stability Module: transmission channel for wider stablecoin price instability

The USDC-PSM worked as expected, just not as intended. Instead of providing "stability" to Dai's peg against the dollar, it created a direct channel of contagion from USDC to Dai. As a result, the USDC-PSM dragged down the price of Dai on secondary markets to USDC's price, even though Dai remained solvent and overcollateralized with respect to its broader collateral pool.

Dai's core defense mechanism for its peg to the dollar was meant to be its primary business of providing Dai-denominated loans against eligible collateral. When the price of Dai falls below par, borrowers on Dai's primary market are incentivized to acquire Dai at a discount from the secondary market, pay back the loans and retrieve their collateral. The repayment of loans burns Dai in the process, removing Dai from circulation and exerting upward pressure on its price on the secondary market. But during the SVB crisis, the amount of Dai burnt through the core lending facilities was vastly exceeded by the number that was minted through the USDC PSM.

The PSMs were designed as a supplemental method of stabilization. However, during the SVB crisis, the dynamics of this mechanism not only dragged down the price of Dai to USDC's but also created a channel of contagion to other stablecoins that otherwise had no direct exposure to SVB or USDC.

The contagion occurred because during this period Dai also operated two additional PSMs accepting other stablecoins as collateral: USDP, issued by Paxos, and GUSD, issued by Gemini. The USDP and GUSD PSMs allowed for a one-to-one exchange between Dai and these stablecoins. Predictably, as Dai lost its peg during the USDC sell-off, investors began to purchase Dai at a discount on secondary markets, exchanging it through the PSMs for the other two stablecoins. Consequently, GUSD and USDP also sold off in the secondary markets.

Figure 5 vividly illustrates how Dai's lines of defense were quickly overwhelmed by the contagion from USDC. The bars represent the net amount of Dai minted (positive) or burned (negative) in the Dai facilities corresponding to each collateral type. USDC, GUSD, and USDP collateral were handled through PSMs, while "other" represents Dai's core lending facilities that provided collateralized loan against other crypto-assets, such as Ethereum, typically with an over-collateralization rate of 150%.

Source: Allium.

The large positive bars in the graph show that during the peak of the USDC sell-off on March 10 and March 11, around 1 billion USDC was deposited into the USDC-PSM on both days, causing the equivalent amount of Dai to be minted.

At the same time, investors were also depositing significant amounts of Dai into the GUSD and USDP PSMs, burning the weakened Dai in exchange for these other stablecoins.

The PSMs served to weaken Dai's own collateral pool. During a period of crisis, the PSMs triggered a significant re-balancing of Dai's collateral pool: from "higher-quality" assets such as Ethereum, over-collateralized at 150%, towards distressed USDC, under-collateralized at less than 100% (due to the USDC depeg). Were the stress on the USDC to continue past the resolution weekend, it is conceivable that Dai's issuer MakerDAO would also have faced solvency concerns.

In the event, MakerDAO instigated emergency changes to the smart contracts underpinning the PSMs, in an (ultimately unsuccessful) attempt to contain the damage.17 MakerDAO proposed a series of emergency parameter changes on the morning of Saturday, March 11, to reduce the daily cap on the USDC-PSM to 250 million and to increase the fee on the facility to 1%. MakerDAO's governance community passed the proposed changes in just over 2 hours. But critically, existing governance rules meant that the changes could only be implemented with a 48-hour delay. By the time these changes were finally executed on Monday, March 13th, most of the market turmoil was already resolved – given the public interventions in the banking sector.

GUSD and USDP were much smaller stablecoins than either USDC or Dai. Over 400 million USDP were withdrawn from the PSM over this period, representing over half of USDP's total outstanding supply. Consequently, USDP depegged to a low of around 91 cents over the weekend. GUSD fell to around 96 cents. Dai's PSMs became a direct source of contagion to these small stablecoins (see Figure 6, top right panel). TUSD, a stablecoin that held a portion of reserves at Signature Bank, which also went into receivership that weekend, also experienced depegging over the weekend.18

Source: CryptoCompare.

Amid the exit from affected stablecoins (USDC, Dai, GUSD, and USDP) during the resolution weekend, there was also a "flight-to-safety" to other unaffected stablecoins. Both Tether (USDT) and Binance USD (BUSD) appreciated over the weekend and traded at a price marginally above their one-dollar peg (bottom right panel of Figure 6).

3. Concluding remarks

We carefully trace the market dynamics for USDC and related stablecoins following SVB's failure in March 2023. We highlight three aspects of the stress event, which may warrant further explorations of the relevant counterfactuals and instigate future studies on the long-term health of stablecoin markets.

3.1 Two-way contagion: from traditional to crypto, then back again

Much attention in the literature, and for policymakers, has been centered around the potential for spillovers from the crypto industry to the traditional financial sector. We highlight, instead, an episode where stress in the banking industry triggered the depegging of a number of major stablecoins. The contagion can operate in both directions. Stress in the stablecoin industry also has the potential to feed back into the traditional financial sector, via possible fire-sale of reserve assets, or as a consequence of broader integration of crypto-assets into traditional finance.

During the SVB episode, the U.S. authorities played a critical role in restoring confidence to the traditional financial sector by fully protecting all depositors (insured or uninsured) in the affected depository institutions. In so doing, they also stabilized the redemption pressure on stablecoins like USDC and Dai.

What would the counterfactual look like? It may be reasonable to expect that the pressure on USDC might have persisted and amplified in the absence of public intervention. Circle's commitment to raising additional funds during the resolution weekend did help to support the price of USDC on secondary markets, but without a continued suspension of the primary market, elevated redemptions volumes could quickly deplete the USDC reserves held in bank deposits, potentially forcing Circle to liquidate its holdings of U.S. Treasury securities in a distressed market. The observable data shows the amount of cash Circle held as reserves in U.S. financial institutions fell from $11.5 billion on March 06, to just $3.7 billion on March 31, despite the official intervention and Circle's assurances.19 Forced liquidation of U.S. Treasury securities, especially in the middle of a banking crisis, could affect the liquidity of the Treasury market, further amplifying the shock to the traditional financial sector.20

Further inter-connectedness between the crypto and traditional industry will likely increase the propensity of two-way contagion going forwards. USDC's holding of U.S. Treasury securities, as of March 2025, is almost twice what it was in March 2023.21

3.2 Maintaining the peg under stress

Stablecoin issuers like Circle point to their high-quality, highly liquid, reserve assets as the fundamental source of their resilience. Yet, the SVB episode demonstrates the potential for at least a proportion of such assets to become inaccessible in a stress scenario. The ensuing concerns around the health of the issuer can lead to significant pressure on its stablecoin peg, and contagion to the broader DeFi industry.

The business model of unregulated stablecoins such as Terra/Luna may be dismissed as extreme cases, and not representative of the industry. But Dai's PSMs exhibit similar hard-coded, smart-contract-based designs that may lead to unintended consequences for the broader sector. Dai's struggles during this episode demonstrate the difficulty of creating dollar-like instruments in the DeFi space without relying on dollar reserves. Yet participants continue to create such products, and the latest iteration of Dai has a higher market capitalization today than at the time of the SVB crisis.22 The regulatory framework established under the GENIUS Act highlights the importance of high-quality backing assets, and it remains to be seen how the market might evolve in response.

Further studies might examine what credible tools stablecoin issuers can employ to manage significant redemption requests. Circle's invocation of banking hours to suspend convertibility over the weekend reflected existing structural differences between traditional financial systems and crypto markets, which may not hold in the future as traditional markets expand hours. Future regulatory frameworks may also alter the tools available to stablecoin issuers to manage significant redemption requests.

3.3 Latent interlinkages that may amplify stress

Circle and Dai's experience during the SVB episode demonstrate that there are significant linkages between firms in the crypto industry. These linkages can be either explicit – as in the case of Dai's PSMs; or implicit, through crises of confidence and other indirect channels of contagion.

Supervision and regulation in the traditional financial sector restrict the extent of spillovers between banks. These guardrails are both explicit — such as large exposure limits on interbank lending; and implicit — such as deposit insurance (including the expectation that authorities might bail out non-insured depositors in systemic events).

In contrast, many stablecoin issuers and DeFi operators have the flexibility to create/suspend lending facilities at their discretion, dynamically creating/destroying interlinkages between broad asset classes. Dai's PSMs illustrate the risks posed by such flexibility, both to the firms creating such facilities and to other firms in the industry. The absence of guardrails and backstops is likely to amplify both the probability and the severity of stress scenarios.

The failure of SVB and its contagion to the stablecoin sector in March 2023 illustrates the need for further research on the interaction between stablecoins and traditional financial sector. A careful assessment of the potential financial stability risks and their mitigants is important for the long-term health and development of the stablecoin industry.

References

Ahmed, Rashad, and Iñaki Aldasoro. Stablecoins and safe asset prices. No. 1270. Bank for International Settlements, 2025.

Allium Labs: Allium Explorer.

CryptoCompare, Enterprise PRO API and Custom Measures Data, https://www.cryptocompare.com/

Federal Reserve Board. "Review of the Federal Reserve's Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley." April 28, 2023.

Financial Stability Board. "The Financial Stability Implications of Multifunction Crypto-asset Intermediaries (PDF)." November 28, 2023.

Gorton, Gary B., and Ellis W. Tallman. Fighting financial crises: Learning from the past. University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Liao, Gordon, Dan Fishman, and Jeremy Fox-Geen. "Risk-based capital for stable value tokens." Available at SSRN (2024).

Ma, Yiming, Yao Zeng, and Anthony Lee Zhang. Stablecoin runs and the centralization of arbitrage. No. w33882. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2025.

Watsky, Cy, Jeffrey Allen, Hamzah Daud, Jochen Demuth, Daniel Little, Megan Rodden, and Amber Seira (2024). "Primary and Secondary Markets for Stablecoins," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 23, 2024.

Appendix: Public Blockchains and Data Sources

We can trace the dynamics of stablecoin stress events in granular detail due to the public nature of blockchain transaction ledgers. Blockchains transmit a significant amount of pseudonymous but publicly available information, as everything from sending tokens to executing smart contract code, is reflected in a publicly visible manner.23

Data related to crypto-asset markets can be broadly categorized into on-chain and off-chain data. On-chain data are sourced or derived from activity occurring on public blockchains. Off-chain data are sourced from third parties based on activity on their off-chain platform.

Though these lines blur significantly – most on-chain data must be aggregated and enriched with off-chain sources, and certainly many off-chain activities will rely on some on-chain processes – this distinction can be helpful for understanding data availability and quality in the space.

Broadly speaking, we use Allium for data on on-chain activities, and CryptoCompare for off-chain activities.

The minting and burning of USDC can be tracked using on-chain data, as every time Circle issues a new batch of tokens onto a public blockchain, that issuance is reflected in data derived from the public blockchain ledger, and vice versa. To track the primary market of USDC, we track transactions where USDC is either being minted (created) or burned (destroyed) on Avalanche, Ethereum, Solana, and TRON.24

To track prices of USDC on secondary markets, we use CryptoCompare pricing data, derived from order book data on CEXs, who run their secondary markets off-chain. Customers of the exchanges send their crypto on-chain to the exchange, which in turn takes custody of the crypto-assets to support trade off its own books and records.

To track trading volumes of USDC on CEXs, we use CryptoCompare's "top tier" exchange volume, which aggregates the trading volumes of exchanges that meet certain risk and data quality standards. To track trading volumes of USDC on DEXs, we use Allium's aggregate DEX volume data. While this captures a large set of DEXs, the majority of volume we track (over 85%) is on Uniswap or Curve.

A note on time zones: we present all data in eastern time. Where necessary, we converted Coordinated Universal Time into eastern standard time up until 2 a.m. on Sunday, March 12, and eastern daylight time thereafter.

1. See: Review of the Federal Reserve's Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank (PDF). Return to text

2. Dai functions as a collateralized loan service, whereby users can borrow Dai tokens, at an agreed-upon interest rate, against crypto collateral. Dai's business model is therefore very different from stablecoins like USDC that are backed by dollar reserves. To support Dai's peg against the dollar, Dai's issuer set up exchange facilities which allowed market participants to exchange Dai with other stablecoins like USDC at an one-to-one basis. Return to text

3. For details on the failure of SVB, see Review of the Federal Reserve's Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank (PDF). Return to text

4. According to Circle, the issuer held over $40 billion total reserve assets at the time. See: Liao and others (2024) and the archived release by Circle: An Update on USDC and Silicon Valley Bank, https://web.archive.org/web/20230311202753/https:/www.circle.com/blog/an-update-on-usdc-and-silicon-valley-bank. Return to text

5. Circle's 2025 registration statement under the Securities Act of 1933: S-1. Return to text

6. An Update on USDC and Silicon Valley Bank, https://web.archive.org/web/20230311202753/https:/www.circle.com/blog/an-update-on-usdc-and-silicon-valley-bank. Return to text

7. See Annex A for a description of our data sources. Return to text

8. See the statement from Circle Chief Executive Officer Jeremy Allaire. We refer to this as the "primary market shutdown," as shorthand for how Circle characterized their "liquidity operations," and seeing as redemptions decreased to minimal levels over the weekend, https://x.com/jerallaire/status/1634649886397267969?s=20. Return to text

9. For all figures, we report the hourly "open" price. Hence the lowest observation in the chart is around 90 cents rather than the 86 cents trough. Return to text

10. See: March 15, 2023 | Update on USDC operations, https://www.circle.com/blog/march-15-update-on-usdc-operations. Return to text

11. Watsky and others (2024) provide a descriptive overview of stablecoin primary and secondary markets and raise several open-ended questions about the SVB episode. Here, we provide more detailed analysis and evidence of how primary and secondary markets for stablecoins relate to each other. Return to text

12. Stablecoins, including USDC, tend to restrict access to their primary markets to a select few institutional investors. Most individual holders are unable to redeem USDC directly from Circle but instead can only trade the coin on the secondary markets. Ma and others (2025) examines the tradeoffs between broadening primary market access to improve price stability on secondary markets and restricting primary access to reduce the risk of runs. What we highlight during the SVB episode is how a suspension of primary market redemption during a crisis can both amplify price instability on the secondary market and exacerbate the run (as evidenced by both falling prices and rising trading volumes). Return to text

13. We use some aggregate measures to track the overall trading volumes. For further details, see the Appendix. Return to text

14. While Dai is commonly referred to as a stablecoin, it differs significantly from stablecoins such as USDC in that it is crypto-collateralized, even as it is designed to maintain a dollar peg, and thus is not redeemed for fiat currency, but rather for crypto-assets. Return to text

15. MakerDAO (the issuer of Dai) operates collateralized lending facilities as its core business model. These facilities accept eligible collateral (typically other crypto assets, such as Ethereum) into its "vaults" and issue loans denominated in Dai. Loans are typically 150% overcollateralized to account for volatility in the price of the collateral. MakerDAO generate profits on the net-interest margin between its Dai-denominated loans and deposits. Return to text

16. Coinbase Pauses Conversions Between USDC and U.S. Dollars as Banking Crisis Roils Crypto, https://www.coindesk.com/business/2023/03/11/coinbase-pauses-conversions-between-usdc-and-us-dollars-as-banking-crisis-roils-crypto. Return to text

17. A full description of reasoning behind proposed changes can be found here Emergency Proposal: Risk and Governance Parameter Changes (11 March 2023) - Legacy / Governance - Sky Forum. Return to text

18. See TrueUSD's statement on March 12, https://x.com/tusdio/status/1635119930092953600. Return to text

19. See: March 2023 USDC Circle Examination Report (PDF) Return to text

20. In a BIS Working Paper, Ahmed and Aldasoro (2025) estimate that "a 2-standard deviation inflow into stablecoin lowers 3-month Treasury yields by 2-2.5 basis points within 10 days. … Stablecoin outflows raise yields by two to three times as much as inflows lower them". Return to text

21. Under proposed legislation, Treasury securities held by stablecoin issuers must be short term. Therefore, stablecoin issuers will hold a specific slice of the overall Treasury market. Return to text

22. As of October 31, 2025, USDS – a rebranding of Dai – has a market capitalization of $9.1 billion (See https://www.coingecko.com/en/coins/usds). Return to text

23. Information such as timestamps, wallet addresses, and value of a given transaction is public. Different blockchains may have different protocols regarding what is publicly available. Return to text

24. We exclude from our analysis any blockchains on which USDC was not available during the time period we study. Two blog posts from Circle allow us to determine this set of blockchains: A blog post from Circle (https://www.circle.com/blog/usdc-coming-to-six-new-blockchains) on August 23, 2023 announced six new blockchains it was launching on, and lists the nine blockchains on which USDC was already issued: Algorand, Arbitrum, Avalanche, Ethereum, Flow, Hedera, Solana, Stellar, and TRON. An earlier blog post in June (https://www.circle.com/blog/usdc-on-arbitrum-now-available) announced USDC's launch on Arbitrum. Thus, we can ascertain that USDC was officially issued on Algorand, Avalanche, Ethereum, Flow, Hedera, Solana, Stellar, and TRON as of the time period we analyze. Of these eight blockchains, we include observations on Avalanche, Ethereum, Solana, and TRON. We make the assumption, due to the small amount of USDC issued on the four blockchains for which we do not have data, the primary market activity on those blockchains would not affect our overall results if we included them. In our analysis, the vast majority of activity we observe is on Ethereum or Tron. Return to text

*On January 8, 2026, a typo in this sentence was corrected to state "$0.34 billion" - as originally intended - instead of "$0.34 million". Return to text

Du, Chuan, Ria Sonawane, and Cy Watsky (2025). "In the Shadow of Bank Runs: Lessons from the Silicon Valley Bank Failure and Its Impact on Stablecoins," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 17, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3958.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.