FEDS Notes

May 27, 2022

The Effect of the War in Ukraine on Global Activity and Inflation

Dario Caldara, Sarah Conlisk, Matteo Iacoviello, and Maddie Penn1

Global geopolitical risks have soared since Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Investors, market participants, and policymakers expect that the war will exert a drag on the global economy while pushing up inflation, with a sharp increase in uncertainty and risks of severe adverse outcomes.2 As an example of these concerns, the April 2022 edition of the International Monetary Fund's World Economic Outlook contains more than 200 mentions of the word "war." Some economic effects are already materializing. The economies of Russia and Ukraine are contracting sharply as a direct result of the war and the sanctions imposed on Russia. Commodity markets are in turmoil and financial markets have been highly volatile since the start of the conflict. In light of these developments, a key question is: How much will geopolitical tensions weigh on economic activity in 2022 and beyond?

In this note, to answer this question, we first quantify the recent rise in geopolitical risks using two measures based on textual analysis: one focusing on newspapers articles, and another constructed from transcripts of firms' earnings calls. Armed with these numerical measures, we use an econometric model and recent data to provide empirical evidence on the global macroeconomic effects of movements in geopolitical risk.

Our main result suggests that the rise in geopolitical risks seen since the Russian invasion of Ukraine will have non-negligible macroeconomic effects in 2022. Relative to a no-war counterfactual, the model sees the war as reducing the level of global GDP about 1.5 percent and leading to a rise in global inflation of about 1.3 percentage points. The adverse effects of geopolitical risks in the model operate through lower consumer sentiment, higher commodity prices, and tighter financial conditions. Additionally, firm-level indicators suggest that a hit to the European economies will likely be greatest, especially in goods-producing industries.

Measurement of Geopolitical Risks

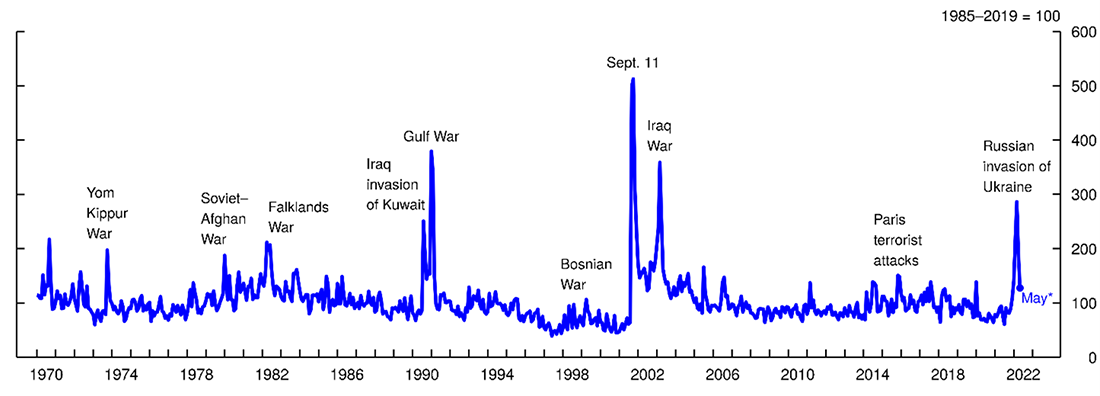

A key challenge to understanding and quantifying the effects of heightened geopolitical tensions pertains to their measurement. Our first measure is the Caldara-Iacoviello geopolitical risk (GPR) index, constructed using searches of newspaper articles that mention adverse geopolitical events and associated risks. The GPR index tracks references to wars, terrorist attacks, and any tensions among states and political actors that affects the course of international relations.3 The index starts in 1900 and is based on automated text searches of the Chicago Tribune, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and, for recent years, seven additional newspapers from the U.S., U.K., and Canada. Figure 1 plots the GPR index since 1970: spikes in the index are associated with wars, risks of war, and major terrorist events. Of note, the index spiked in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine—in March 2022, readings of the index reached one of the highest values in the past 50 years, comparable with similar peaks during the Gulf and Iraq Wars.

Note: The figure plots the Caldara-Iacoviello geopolitical risk (GPR) index from January 1970 through May 2022. The index is constructed merging the historical GPR index from 1970 through 1984, with the recent GPR index from 1985. The index is normalized to average 100 throughout the 1985-2019 period. Spikes are labeled with significant geopolitical events. *Preliminary Reading.

Source: Federal Reserve Board staff calculations based on Dario Caldara and Matteo Iacoviello (2022), “Measuring Geopolitical Risk,” American Economic Review.

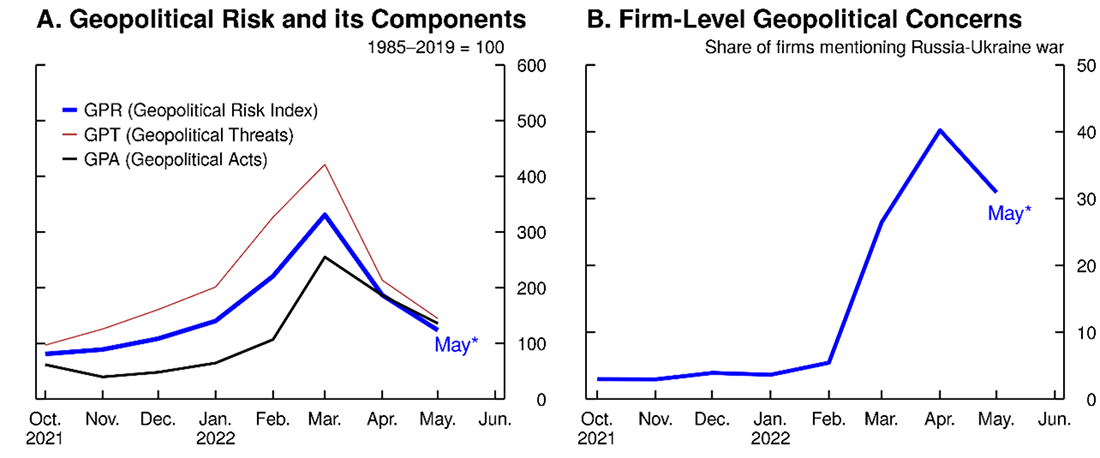

The two building blocks of the overall GPR index are the geopolitical threats (GPT) index, which captures concerns about scope, duration, and ramifications of geopolitical tensions and conflicts, and the geopolitical acts (GPA) index, which captures events such as the start and the actual unfolding of wars.4 As shown in the left panel of Figure 2, the GPT index, which surged between January and March, declined in April and May, consistent with the view that extreme outcomes of the war, such as direct involvement of more countries, are perhaps perceived as less likely. The GPA index also spiked in the aftermath of the invasion and is retracting, albeit more slowly.

Note: The left panel plots recent movements in the GPR index and its two sub-components, the geopolitical threats (GPT) and geopolitical acts (GPA) indexes. The right panel plots the evolution in the share of globally listed firms’ earnings calls that mention concerns over conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Both panels extend from October 2021 to May 2022. *Preliminary Reading.

Source: Federal Reserve Board staff calculations; S&P Global market intelligence.

We complement information from the GPR index with a second, alternative measure of geopolitical risks constructed by searching the transcripts of the earnings call of globally listed firms for mentions of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.5 Concerns about the conflict have been pervasive in earnings conference calls across the globe, with 40 percent of all earnings calls held in April 2022 explicitly mentioning the conflict. As the right panel of Figure 2 shows, the geopolitical risk measure based on earnings calls shares very similar dynamics to the newspaper-based indexes, lending support to the notion that the newspaper-based GPR indexes are capturing information that is relevant to firms and investors.

Quantifying the Effects of Higher Geopolitical Risks on GDP and Inflation

Historically, periods of elevated geopolitical risks have been associated with sizable negative effects on global economic activity.6 Wars destroy human and physical capital, shift resources to less efficient uses, divert international trade and capital flows, and disrupt global supply chains. Additionally, changing perceptions about the range of outcomes of adverse geopolitical events may further weigh on economic activity by delaying firms' investment and hiring, eroding consumer confidence, and tightening financial conditions.

Our numerical measure of geopolitical risk allows us to quantify the effects of its recent spike on global economic activity. To this end, we estimate a structural vector autoregression (VAR) model and use the estimated model to quantify the effects over time of the recent spike in geopolitical tensions. The model includes monthly measures of world GDP, world inflation, global stock prices, real oil prices, the broad real dollar, commodity prices, global consumer confidence, and the geopolitical threats (GPT) and geopolitical acts (GPA) indexes.7 The VAR model uses data from January 1974 through April 2022 and includes three lags.8 We assume that changes in the GPT and GPA indexes drive all within-month fluctuations in the other economic variables, so that any contemporaneous correlation between geopolitical risks and financial variables, say, is assumed to reflect the effect of geopolitical risks on financial variables, rather than the other way around. But with a lag, each variable can affect all variables.

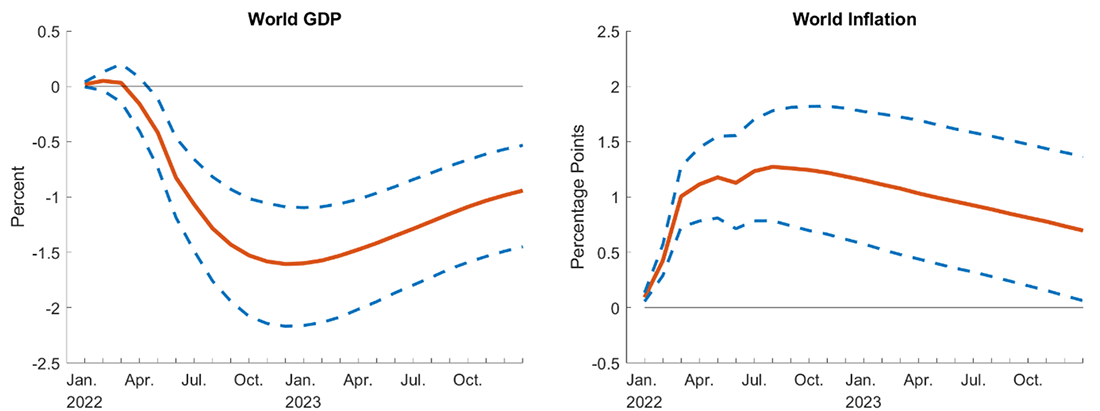

Figure 3 uses a historical decomposition of the estimated VAR results to simulate the effects over time on global GDP and inflation of the heightened geopolitical risks since January 2022. The rise in geopolitical risks observed thus far this year produce a drag on world GDP that builds throughout 2022, cumulating to a negative impact of around 1.7 percent on the level of global output. Similarly, the rise in geopolitical risks boosts prices, causing an increase in global inflation of 1.3 percentage points by the second half of 2022, after which the effects begin to subside.

Note: The figure plots the response over time of world GDP (left panel) and world inflation (right panel) to a rise in geopolitical risks sized to mimic the increase occurred between January and April 2022. The solid red lines in the figure plot the central estimates. The dashed blue lines denote the 70 percent confidence intervals. The variables are plotted from January 2022 to December 2023 in deviation from a no-war baseline.

Source: Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

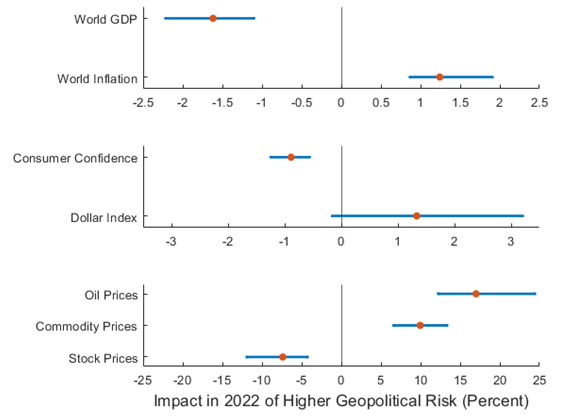

How are geopolitical risks transmitted to the global economy? With various channels controlled for, the structural VAR estimates leave us well-positioned to answer this question. Figure 4 presents a more detailed picture of the way the global economy responds to a geopolitical risk shock. The effects of elevated geopolitical risks in 2022 are associated with declining consumer confidence and stock prices, factors that weaken aggregate demand. The exchange value of the dollar appreciates, in line with the evidence that spikes in global uncertainty and adverse risk sentiment can trigger flight-to-safety international capital flows (Forbes and Warnock, 2012). Commodity prices and oil prices increase, putting downward pressure on global activity and upward pressure on inflation.

Note: The figure plots the maximum impact in the first year of a rise in geopolitical risks sized to mimic the increase occurred between January and April 2022. For each variable, the red dots plot the central estimates of the maximum impact in the first year. The blue bars denote 70 percent confidence intervals. The effect is measured in percent deviation from a no-war baseline for all variables except inflation, for which it is measured in percentage points.

Source: Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

Country and Industry Exposure to the Conflict.

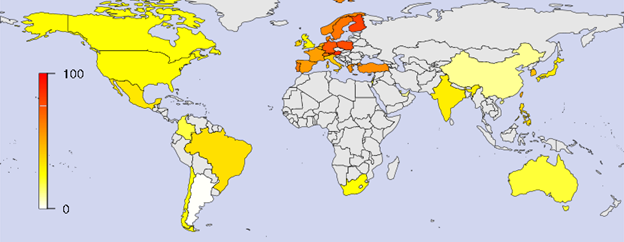

The regional nature of many geopolitical risks suggests that their economic repercussions may not be distributed evenly around the globe. We gauge the exposure of a country to the current conflict by calculating the share of firms that mention the Russian invasion of Ukraine in their quarterly earnings calls, based on the country where the firm is headquartered.9 Figure 5 visualizes country exposure in a map of the world, with warmer colors denoting higher exposure. Countries in Europe, and especially those that are in proximity to the conflict, are the most exposed. Roughly 80 percent of firms in Finland and Poland, countries sharing a border with Russia or Ukraine, are concerned about the war. For Germany, a country with high exposure to the conflict through the import of energy from Russia, the fraction of firms mentioning the conflict is 75 percent. The rest of the world does not appear to be exposed as intensely.10 All told, this evidence is suggestive of the risk that European countries may suffer relatively more from the economic fallout from the conflict.

Note: This chart depicts the exposure of a country to the Russia-Ukraine war, calculated using the share of firms’ earnings calls mentioning the Russia–Ukraine war, based on the country where the firm is headquartered. Earnings calls’ share is calculated for countries with at least 10 earnings calls between March 1, 2022, and May 13, 2022. Countries with no earnings calls or with less than 10 earnings calls are shown in gray. White indicates that no firm mentions concerns related to the conflict, while deep red indicates 100 percent of firms mentioning concerns related to the conflict.

Source: Federal Reserve Board staff calculations; S&P Global market intelligence.

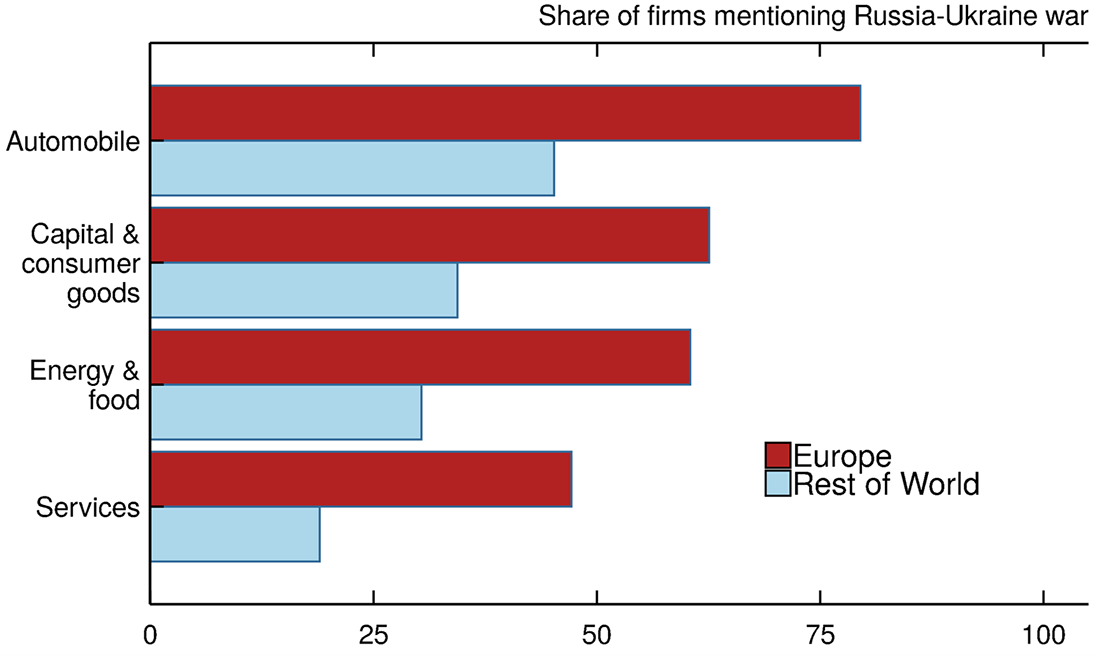

The economic effects of the conflict are also likely to be heterogeneous by type of industry. Figure 6 calculates the share of firms that mention the Russian invasion of Ukraine in their quarterly earnings calls based on their industry of operation. The effect of the current conflict appears more concentrated in goods-producing industries that reportedly had been experiencing bottlenecks even before the Russian invasion, with an incidence of around 80 percent among European automobile companies. Meanwhile, industries that are less affected by supply disruptions—such as services—are less likely to express concerns over the war.

Note: This chart illustrates the share of firms’ earnings calls mentioning the Russia–Ukraine war between March 1, 2022, and May 13, 2022, based on firms’ industry of operation and geographic location. Industry classifications are based on the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS). Note: Russian and Ukrainian firms are excluded from the Europe region. Aggregation from the GICS is as follows: Automobile includes Automobile & Components. Capital & consumer goods includes Capital Goods, Consumer Durables & Apparel, Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment, Software & Services, and Technology Hardware & Equipment. Energy & Food includes Energy, Food & Staples Retailing, Food, Beverage & Tobacco, Household & Personal Products, and Materials. Services includes Banks, Commercial & Professional Services, Diversified Financials, Health Care Equipment & Services, Insurance, Media & Entertainment, Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology & Life Sciences, Retailing, and Telecommunication Services.

Source: Federal Reserve Board staff calculations; S&P Global market intelligence.

Concluding Remarks.

The increased geopolitical risks induced by the Russian invasion of Ukraine will weigh adversely on global economic conditions throughout 2022. Such effects are estimated in our model to reduce GDP and boost inflation significantly, exacerbating the policy trade-offs facing central banks around the world. While sizeable, these effects do not appear to be large enough to derail the global recovery from the pandemic. However, the future of the war is highly uncertain, and unforeseen developments in the conflict could generate further changes to geopolitical risk and worsen its economic effects.

References

Anayi, Lena, Nicholas Bloom, Philip Bunn, Paul Mizen, Gregory Thwaites, and Ivan Yotzov (2022), "The impact of the war in Ukraine on economic uncertainty", VoxEU.org, 16 April.

Caldara, Dario, and Matteo Iacoviello (2022), "Measuring Geopolitical Risk," American Economic Review, vol. 112 (April), pp. 1194–225.

Cuba-Borda, Pablo, Alexander Mechanick, and Andrea Raffo (2018), "Monitoring the World Economy: A Global Conditions Index," IFDP Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 15.

Federle, Jonathan, Andre Meier, Gernot Müller, and Victor Sehn (2022), "Proximity to War: The stock market response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine", CEPR Discussion Paper 17185.

Forbes, Kristin J. and Francis E. Warnock (2012), "Capital flow waves: Surges, stops, flight, and retrenchment," Journal of International Economics, vol 88 (2), pp. 235-251.

1. Federal Reserve Board, Division of International Finance. All errors and omissions are responsibility of the authors. The views expressed in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of anyone else associated with the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. See, for example, the discussion on the likely effects of the war in Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell's press conference after the May 3-4, 2022, meeting of Federal Open Market Committee. Transcript available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20220504.pdf. Anayi et al (2022) show that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to an increase in several measures of economic uncertainty. Return to text

3. For a more detailed description, see Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). Return to text

4. The GPT index searches phrases in newspaper articles that are related to war, military, nuclear, and terrorist threats. The GPA index searches phrases referring to the beginning or the escalation of wars or to the occurrence of terrorist events. Return to text

5. At the firm level, we construct geopolitical concerns related to the current conflict by counting mentions of war-related words (such as "war" or "invasion") together with "Russia" or "Ukraine." Analogous, broader measures of firm-level geopolitical concerns (based on searches that do not necessarily include the words "Russia" or "Ukraine") show a similar pattern. Return to text

6. Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) show that, across countries and over time, higher geopolitical risks are associated with higher probability of economic disasters, lower expected GDP growth, and higher downside risks to GDP growth. Return to text

7. We measure stock prices with the FTSE World Dollar index, commodity prices with the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index, confidence with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development's Consumer Confidence Index, and oil prices with the West Texas Intermediate Index. Inflation is from Global Financial Data. Monthly GDP is based on purchasing power parity and is constructed using the methodology described in Cuba-Borda, Mechanick and Raffo (2018). Return to text

8. Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) estimate a quarterly VAR model of the US economy to look at the dynamic effects of geopolitical risks. Our VAR here extends their work by using a longer sample (we start in 1970 instead of 1985), using monthly data, and looking at global rather than US effects, with a focus on inflation. Return to text

9. Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) show that high firm-level geopolitical risk—calculated using similar textual analysis techniques described in this note—reduces firm-level investment. Return to text

10. Recent work by Federle et al. (2022) highlights the spatial dimension of the economic spillovers from the Ukraine war. They identify a 'proximity penalty' in equity returns: the closer a country is to Ukraine, the more pronounced the decline in its equity market around the time the war started. Return to text

Caldara, Dario, Sarah Conlisk, Matteo Iacoviello, and Maddie Penn (2022). "The Effect of the War in Ukraine on Global Activity and Inflation," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May 27, 2022, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3141.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.