FEDS Notes

January 16, 2025

The Global Transmission of Inflation Uncertainty1

Thomas H. Li, Juan M. Londono, and Sai Ma

1. Introduction

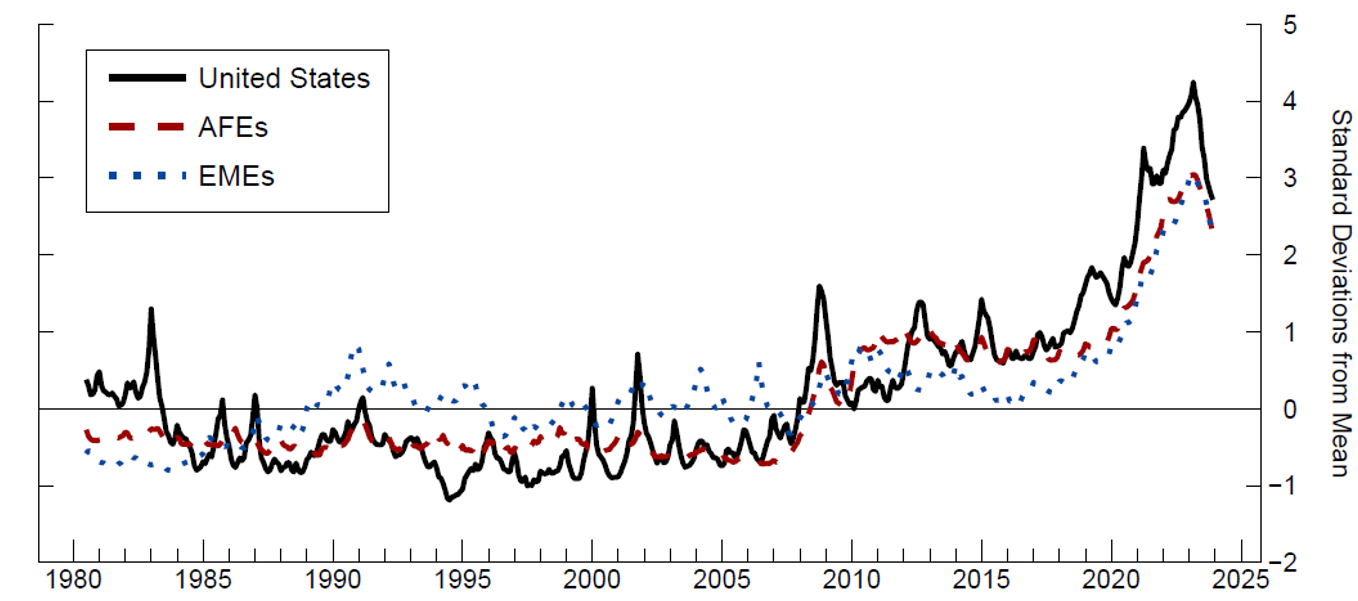

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented disruptions to global supply chains, labor markets, and economic activity, leading to significant volatility in inflation rates worldwide. Not only the level of inflation but the uncertainty about the future path of inflation increased considerably since the onset of the pandemic and have remained elevated until very recently, posing challenges for policymakers and businesses alike. Figure 1 shows a measure of inflation uncertainty proposed in a recent paper by Londono, Ma and Wilson (2024) (LMW hereafter). The intuition behind this measure is that inflation uncertainty is higher when inflation becomes objectively harder to predict. In the case here, we follow the methodology of LMW and use a range of inflation metrics and a large set of global financial and economic variables as predictors. As can be seen in the figure, inflation uncertainty in the U.S. has remained exceptionally elevated since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and reached a record high in March 2023—about four standard deviations above its historical mean between 1980 and 2023. This surge in uncertainty was widespread, as seen when we average the inflation uncertainty measures for sets of advanced foreign and emerging market economies.2 Inflation uncertainty is thus highly correlated across countries, especially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a result that aligns well with both the global nature of the forces influencing inflation and that substantiates the challenges experienced in predicting inflation since the onset of the pandemic.3 In this note, we explore the economic consequences of the global nature of inflation uncertainty by documenting how inflation uncertainty and its economic consequences transmit across countries.

Note: Inflation uncertainty for advanced foreign and emerging market economies are computed by standardizing each country's uncertainty series over their historical mean (July 1980 to December 2023) before taking the equal-weighted average across the respective countries in each region.

Source: Londono, Ma and Wilson (2024).

2. The causes and consequences of inflation uncertainty

The rise of global inflation uncertainty can stem from multiple sources, including volatile commodity prices, geopolitical tensions, and unpredictable future responses of fiscal and monetary policies. For instance, the impact of volatile commodity prices, particularly oil, on inflation uncertainty has been widely discussed (Blanchard and Gali, 2007). Geopolitical tensions, such as trade wars and regional conflicts, also contribute significantly to inflation volatility (Caldara et al., 2016). Additionally, unpredictable fiscal and monetary policies can exacerbate inflation uncertainty, as seen in various analyses of policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (see, for instance, Baker et al., 2020).

Inflation uncertainty has significant and economically meaningful economic repercussions. LMW find that an increase in U.S. inflation uncertainty is followed by a significant drop in industrial production, which is explained mostly by the drop in investment. An increase in inflation uncertainty makes investment projects less desirable, and this effect is explained by the interaction between inflation uncertainty and future monetary policy rates and by the increase in the uncertainty about input costs. They also find that foreign inflation uncertainty has effects on U.S. investment, and these effects are additional to those of domestic inflation uncertainty and the level of domestic and foreign inflation.

3. How does inflation uncertainty transmit across countries?

To explore the mechanisms of transmission of inflation uncertainty across countries, we propose the following panel-data regression wherein foreign inflation uncertainty in any country $$j$$ can affect future domestic outcomes in any other country $$i$$ beyond the effect of domestic inflation uncertainty:

$$$$ Out_{i,t+h} = \alpha_{i,j} + \beta_{dom} InfU_{i,t} + \beta_{for} InfU_{j,t} + \Upsilon \mathbf{C_{i,j,t}} + \epsilon_{i,j,t}.\ (1) $$$$

$$ Out_{i,t+h} $$ is one of the following economic outcomes: inflation uncertainty, monetary policy rate, or investment growth. $$ InfU_{i,t} $$ represents the inflation uncertainty of the domestic country $$i$$, which is standardized to facilitate interpretation in terms of the effects of shocks to inflation uncertainty. Because inflation uncertainties are highly correlated across countries, $$ InfU_{j,t} $$ represents the portion of the foreign country $$j$$'s inflation uncertainty that is orthogonal to $$ InfU_{i,t} $$. $$ \mathbf{C_{i,j,t}} $$ contains controls for the level of inflation in countries $$i$$ and $$j$$, monetary policy rates in countries $$i$$ and $$j$$, financial uncertainty as measured by the VIX, and a COVID-19 dummy that takes a value of 1 during the periods 2020:Q1 to 2022:Q2.

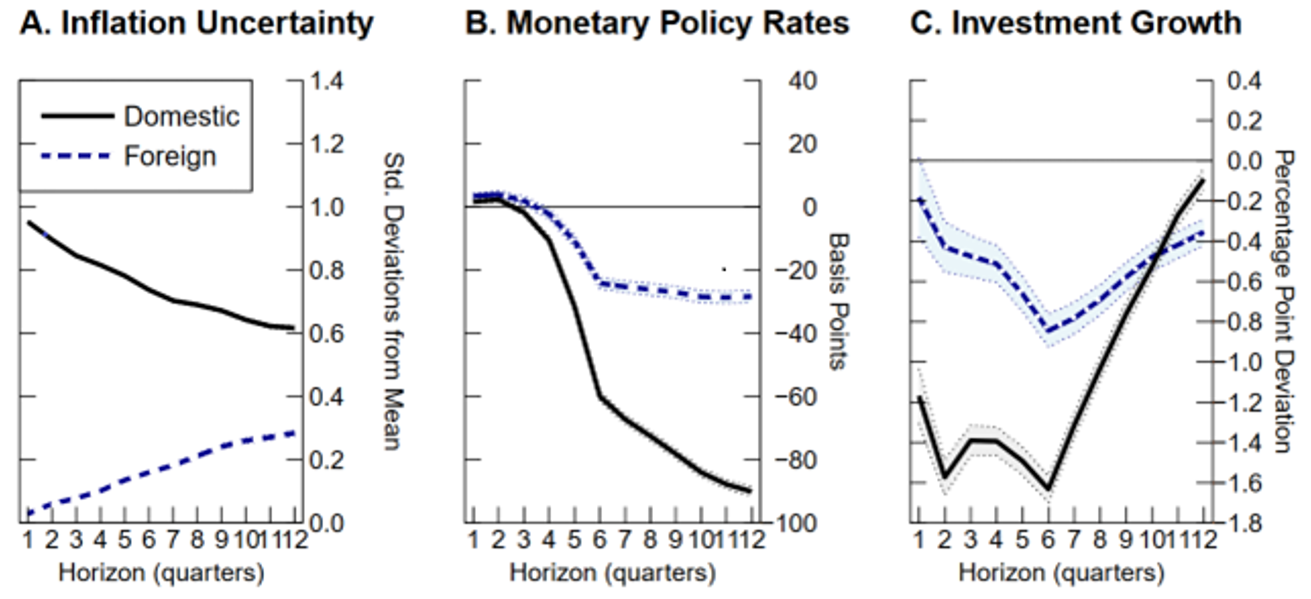

Note: The figure illustrates the impact of one-standard deviation shocks in domestic and foreign inflation uncertainty on $$h$$ quarters ahead (domestic) inflation uncertainty (panel A), the monetary policy rate (panel B), and investment growth between $$t$$ and $$t+h$$ (panel C). The dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Author calculations.

Figure 2 shows the international spillover effects ($$ \beta_{for} $$) of inflation uncertainty and compares these with the domestic inflation uncertainty effects ($$ \beta_{dom} $$). Inflation uncertainties are dynamically correlated across countries, as suggested by the positive and significant effect of foreign inflation uncertainty on future domestic inflation uncertainty (panel A), although, as expected, international spillovers are smaller in magnitude than domestic effects, especially in short- to mid-term horizons. An increase in both domestic and foreign inflation uncertainty is followed by a drop in domestic monetary policy rates, which suggests that, all control variables constant, when faced with higher uncertainty about the path of domestic and foreign inflation, monetary authorities, on average, lower interest rates. Inflation uncertainty also has real economic international spillover effects, which are manifested by the decrease in domestic investment following an increase in foreign inflation uncertainty. The real economic spillover effects are smaller in magnitude than the domestic real economic effects—a three standard deviation increase in foreign (domestic) inflation uncertainty, which is similar to the cross-country average shock observed in March 2023, is followed by a drop in investment of 2.55 percent (4.9 percent) after 6 quarters.

Our results illustrate the complexity of the international transmission of inflation uncertainty to the real economy. Assuming that all control variables and domestic inflation uncertainty remain constant, an increase in foreign inflation uncertainty is followed, on average across all countries, by an increase in future domestic inflation uncertainty, lower future policy rates, and a decrease in future investment. However, monetary and fiscal authorities in all countries can have different reaction functions to an increase in the level of inflation and the uncertainty about the future path of inflation. For instance, during the post-COVID recovery, the negative rate gap between U.S. policy rates and the eurozone widened moderately, while the gap with Japanese rates widened considerably. In contrast, during this episode, there is a marked widening of the positive gap with several emerging market economies. These heterogeneous reactions can, in turn, imply different domestic and international spillover effects across countries. To explore the possibility of heterogeneous effects across countries, we propose the following panel-data setting wherein the international spillover effects depend on the interest rate differential between the foreign ($$j$$) and the domestic ($$i$$) country ($$IRD_{i,j}$$) and the domestic effects are country specific:

$$$$ \Delta inv_{i,t+h} = \alpha_{i,j} + \beta_{dom,i,j} InfU_{i,t} + (\beta_{for} + \beta_{IRD} IRD_{i,j,t-1}) InfU_{j,t} + \Upsilon \mathbf{C_{i,j,t}} + \epsilon_{i,j,t}.\ (2)$$$$

Table 1 reports the coefficients associated with international spillovers, $$ \beta_{for} $$, and the additional effects of interest rate differentials, $$ \beta_{IRD} $$. The coefficients for the effect of inflation uncertainty, $$ \beta_{for} $$, remain negative and significant. The coefficients for the additional role of monetary policy rate differentials in the transmission of foreign inflation uncertainty are consistently positive and highly significant across all horizons, which suggests that differences in monetary policy rates could modulate the transmission of foreign inflation uncertainty to domestic investment.4

Table 1: Determinants of international inflation uncertainty transmission

| $$h = 1$$ | $$h = 2$$ | $$h = 3$$ | $$h = 4$$ | $$h = 6$$ | $$h = 8$$ | $$h = 12$$ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monetary policy differential | $$ \beta_{for} $$ | 0.01 | −0.263∗∗∗ | −0.279∗∗∗ | −0.285∗∗∗ | −0.619∗∗∗ | −0.519∗∗∗ | −0.154∗∗∗ |

| (0.10) | (−4.16) | (−5.38) | (−6.12) | (−15.22) | (−13.85) | (−4.69) | ||

| $$ \beta_{tr} $$ | 0.453∗∗∗ | 0.422∗∗∗ | 0.374∗∗∗ | 0.381∗∗∗ | 0.453∗∗∗ | 0.421∗∗∗ | 0.344∗∗∗ | |

| (6.22) | (9.22) | (10.03) | (11.44) | (15.69) | (15.95) | (14.27) | ||

Note: The table reports coefficient estimates of $$ \beta_{for} $$ and $$ \beta_{tr} $$ for varying horizons alongside $$t$$-statistics below in parentheses. Horizon steps are in quarters. Significance: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

4. Quantifying the implications for the U.S.

While the results in Figure 2 and Table 1 are obtained using all country pairs, we can isolate the international spillovers of inflation uncertainty for U.S. investment and how these effects vary depending on interest rate differentials with other economies.

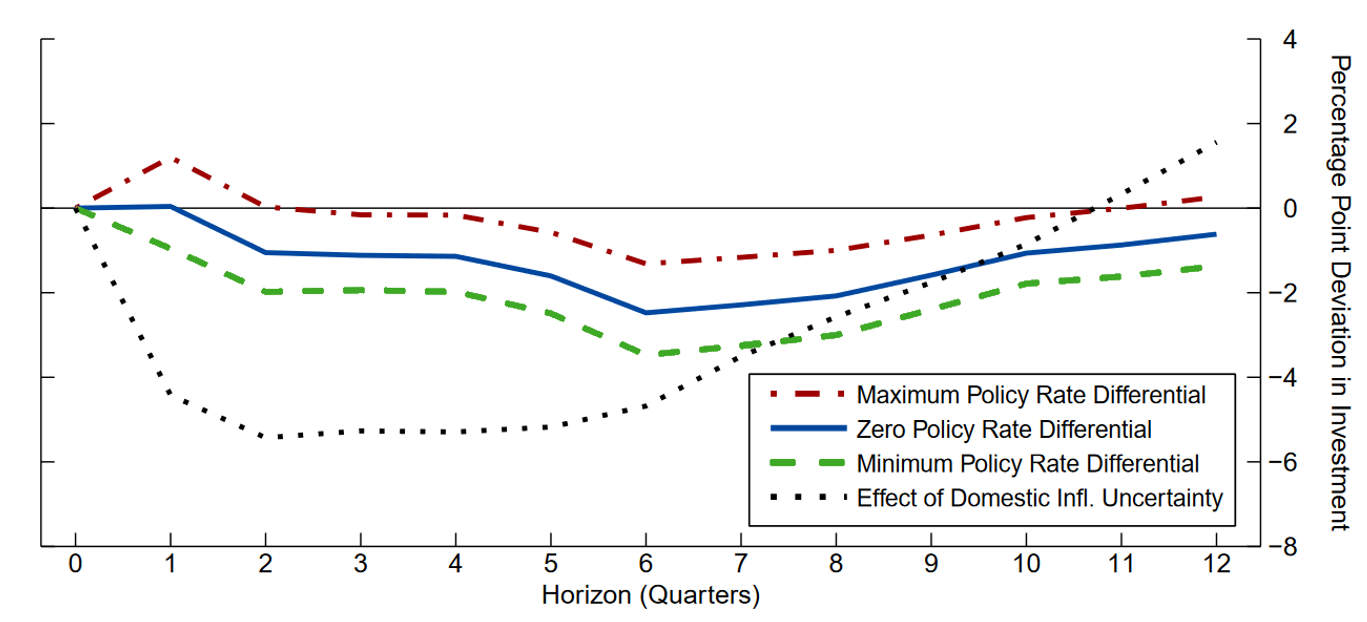

Figure 3 shows the effect of foreign inflation uncertainty on U.S. investment for different levels of monetary policy differentials. As a reference, the dotted black line represents the effect of domestic inflation uncertainty on U.S. investment, while the solid blue line indicates the effect of foreign uncertainty on U.S. investment when the monetary policy rate differential is zero. The impact of foreign inflation uncertainty on U.S. investment is economically meaningful and approximately half as large as the effect of domestic inflation uncertainty—a four standard deviation shock in foreign inflation uncertainty, which is similar to the shock observed in March 2023, is followed by a drop in investment of over 2 percent after 6 quarters. There is significant heterogeneity in the effect on U.S. investment across foreign countries. In particular, inflation uncertainty stemming from countries with policy rates lower than those for the U.S. (that is, with negative monetary policy rate differentials), such as Japan (dashed orange line), exhibit a more pronounced impact on U.S. investment. This suggests that when the policy rate differential with the U.S. is low, heightened foreign inflation uncertainty can exert a larger impact on U.S. economic activity.

Figure 3. Effect of foreign inflation uncertainty on U.S. investment growth for different levels of monetary policy rate differentials

Note: The figure illustrates the impact of heterogeneity in monetary policy rate differentials on the relationship between foreign inflation uncertainty and investment growth in the United States. It depicts the pure effect of U.S. domestic inflation uncertainty on investment as a baseline reference. Additionally, it shows the total effect of foreign inflation uncertainty at three distinct levels: (1) the largest average policy rate differential after 2021, represented by the Czech Republic; (2) the smallest average policy rate differential after 2021, represented by Japan; and (3) a scenario with a zero policy rate differential.

Source: Author calculations.

5. Conclusion

Earlier work shows that inflation uncertainty has a negative effect on the macro economy in addition to the costs of inflation itself and that the channel works primarily through its drag on investment. This work shows that high inflation uncertainty abroad has an independent effect on the domestic economy, and this effect manifests in an increase in domestic inflation uncertainty, a reduction in monetary policy rates, and a decrease in investment. Moreover, the international spillover effect of inflation uncertainty on investment varies across countries depending on differences in monetary policy rates, which tend to decouple in episodes of high uncertainty. This result suggests that the global rise in inflation uncertainty seen during the COVID-19 period has been an additional headwind on economies.

References

Baker, Scott R., Nicholas Bloom, Steven J. Davis, and Stephen J. Terry, "COVID- Induced Economic Uncertainty," National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

Blanchard, Olivier J. and Jordi Gali, "The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Shocks: Why Are the 2000s So Different from the 1970s?," National Bureau of Economic Research, 2007.

Caldara, Dario, Michele Cavallo, and Matteo Iacoviello, "Oil Price Elasticities and Oil Price Fluctuations," International Finance Discussion Papers, 2016, 1173.

Cascaldi-Garcia, Danilo, Luca Guerrieri, Matteo Iacoviello, and Michele Modugno, "Lessons from the Co-movement of Inflation around the World," FEDS Note, Federal Reserve Board, 2024.

Londono, Juan M., Sai Ma, and Beth Anne Wilson, "The Unseen Cost of Inflation: Measuring Inflation Uncertainty and Its Economic Repercussions," Federal Reserve Board Working Paper, 2024.

1. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors. Return to text

2. Our sample consists of quarterly inflation uncertainty time series spanning 1980:Q1 to 2023:Q4. We consider the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Return to text

3. We further confirm empirically that post-pandemic inflation uncertainty is largely global by documenting an increase in country pair correlations and by using a dynamic factor model such as the one in Cascaldi-Garcia et al. 2024 that isolates the common component across countries' inflation uncertainties. This model suggests limited country-specific variations after the onset of the pandemic. Return to text

4. Our findings of the significantly negative effects of foreign inflation uncertainty and the statistical significance of the monetary policy channel remain robust to a battery of alternative specifications. In particular, we achieve similar results when using only the pre-COVID-19 sample and when adding controls for the non-inflation component of total economic uncertainty and relative economic size. Return to text

Li, Thomas H., Juan M. Londono, and Sai Ma (2025). "The Global Transmission of Inflation Uncertainty," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 16, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3692.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.