FEDS Notes

August 06, 2019

U.S. Corporations' Repatriation of Offshore Profits: Evidence from 2018

Michael Smolyansky, Gustavo Suarez, Alexandra Tabova1

Abstract: We investigate how companies with large holdings of cash abroad have used those funds following the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which eliminated prior tax disincentives on the repatriation of foreign earnings. The data cover 2018, a year after the TCJA was passed. A previous note, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/us-corporations-repatriation-of-offshore-profits-20180904.htm, asked the same question, but covered only 2018:Q1, the latest available data at the time.

Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, foreign profits of U.S. multinational enterprises (MNEs) were subject to U.S. taxes, but only when repatriated. This system incentivized firms to keep profits abroad, and, by the end of 2017, U.S. MNEs had accumulated approximately $1 trillion in cash abroad, held mostly in U.S. fixed-income securities.2 Under the TCJA, the United States shifted to a quasi-territorial tax system in which profits are taxed only where they are earned (subject to minimum taxes); henceforth, U.S. MNEs' foreign profits will therefore no longer be subject to U.S. taxes when repatriated. As a transition to this new tax system, the TCJA imposed a one-time tax (payable over eight years) on the existing stock of offshore holdings regardless of whether the funds are repatriated, thus eliminating the tax incentive to keep cash abroad.3

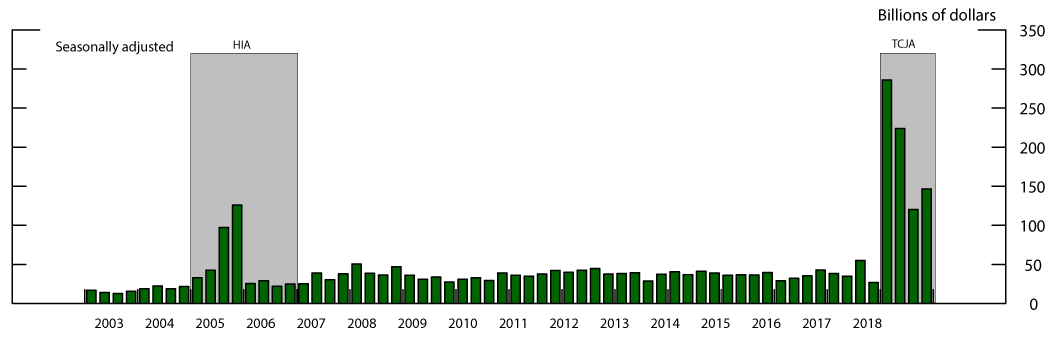

Balance of payments data show that U.S. firms repatriated $777 billion in 2018, roughly 78 percent of the estimated stock as of end-2017 of offshore cash holdings. Repatriation was strongest in the first half of 2018, when $510 billion was brought back, and continued throughout 2018, albeit at a slower pace (figure 1). Despite this slowing down, repatriation flows could remain above their pre-TCJA levels because the TCJA eliminated the tax incentives for keeping profits abroad. For reference, the Homeland Investment Act of 2004 (HIA, also known as the "tax holiday"), which provided a temporary one-year reduction in the repatriation tax rate, resulted in $312 billion repatriated in 2005, of an estimated $750 billion held abroad.4 It should be noted that repatriation reflects the transfer of funds to the United States in purely accounting terms: The funds previously held by a foreign affiliate are now held by the U.S. parent.

Note: Homeland Investment Act (HIA) shaded area extends from 2005:Q1 to 2006:Q4. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) shaded area extends from 2018:Q1 to 2018:Q4.

Source: BEA Balance of Payments data.

The potential effect of repatriated funds since the passage of the TCJA on firm financing patterns and investment decisions has garnered considerable investor attention.5 The analysis detailed here shows that funds repatriated in 2018 have been associated with a sharp increase in share buybacks. The evidence of an effect on investment is not as clear cut. While the data show an increase in investment in 2018 by the top repatriating firms, investment by such firms had already been on an upward trend prior to the TCJA, making it arguably more difficult to know how much of the increase can be attributed specifically to repatriation versus other contemporaneous factors, like other changes in policy or economic conditions. Of course, it may be too early to reach a definitive conclusion, as increases in investment may take longer to fully materialize.

Our analysis investigates how U.S. nonfinancial firms with large holdings of cash abroad—specifically the top 15 holders—have deployed the repatriated funds, comparing their financing and investment behavior with that of all other nonfinancial S&P 500 firms.6 Before the passage of the TCJA, the top 15 cash holders accounted for roughly 80 percent of total offshore cash holdings, and roughly 80 percent of their total cash (domestic plus foreign) was held abroad.

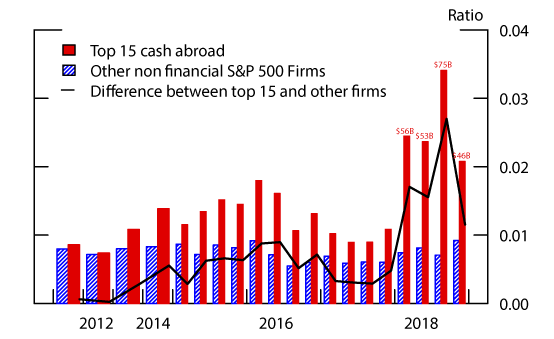

Figure 2 shows that immediately after the passage of the TCJA in late December 2017, share buybacks rose sharply for the top 15 cash holders, with the ratio of buybacks to assets more than doubling in 2018 (red bars).7 In dollar terms, buybacks among this group of firms increased from an annual total of $86 billion in 2017 to $231 billion in 2018. Even among the top 15 cash holders, the largest holders accounted for the bulk of the share repurchases: in 2018, the top 5 cash holders accounted for 65 percent of the total repatriated by the top 15, and the top holder alone accounted for 32 percent. Buybacks for nonfinancial S&P 500 companies other than the top 15 cash holders also increased (blue bars), but by notably less than buybacks for the top 15 holders; as a result, the difference in the buybacks-to-assets ratio between the two groups more than doubled in the year following the passage of the TCJA (black line). Firms can also pay out cash to shareholders through dividends; however, unlike buybacks, dividends were virtually unchanged for the top 15 cash holders relative to the same period the year before. Similarly, academic studies suggest that most of the repatriated funds during the HIA of 2004 were used to fund share buybacks (see Dharmapala, Foley, and Forbes (2011)).

Note: For years before 2015, annual averages of quarterly values are shown.

Source: Compustat; Bloomberg.

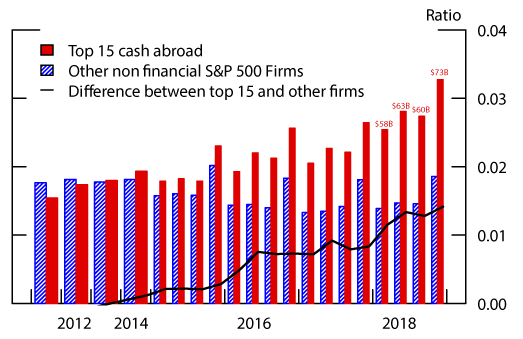

Investment by the top 15 cash holders also rose in 2018 (figure 3), particularly relative to other nonfinancial S&P 500 firms (black line).8 However, the increase in investment was far less notable than the increase in share buybacks. For the top 15 cash holders, the average ratio of investment (capital expenditures plus research and development expenses) to assets rose from 2.3 percent in 2017 to 2.8 percent in 2018, while it remained flat at 1.5 percent for other nonfinancial S&P 500 firms.9 However, it should be noted that investment by the top 15 cash holders was already on an upward trajectory for several years prior to the TCJA—both in dollar terms (red bars), and relative to other nonfinancial S&P 500 firms (black line). Given this pre-existing upward trend, it is difficult to know how much of the observed increase in investment by the top 15 cash holders might have occurred even in the absence of the repatriation. Moreover, the increase in investment by the top 15 cash holders before the passage of the TCJA is consistent with the notion that, because these are large firms, they are unlikely to have faced notable constraints or costs to accessing capital markets to fund their investment needs. Of course, it may be too early to reach a definitive conclusion, as any additional boost to investment due to the repatriation may take more time to fully materialize.10

Note: For years before 2015, annual averages of quarterly values are shown. R&D is reaerch and development.

Source: Compustat; Bloomberg.

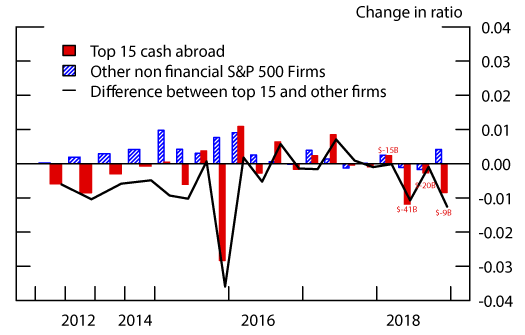

The repatriating firms may have also chosen to pay down debt; indeed, the aggregate debt of the top 15 cash holders declined by $84 billion in 2018 (figure 4). In contrast, the aggregate debt of nonfinancial S&P 500 firms other than the top 15 cash holders increased by $157 billion in 2018. As shown in figure 4, however, the decline in the debt-to-assets ratio of the top 15 cash holders was not particularly large (dropping by 2 percentage points, or from about 32 percent in 2017:Q4 to 30 percent in 2018:Q4).11

Note: For years before 2015, annual averages of quarterly values are shown.

Source: Compustat; Bloomberg.

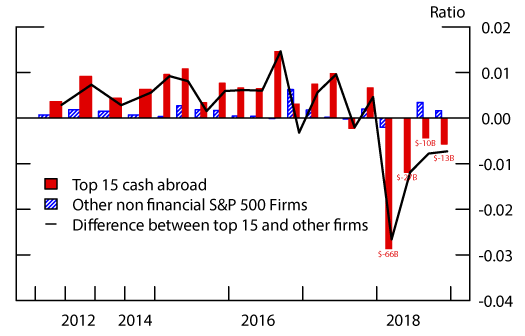

The analysis so far suggests that the strongest effect of repatriation was on share buybacks. We now ask how the repatriation may have contributed to funding these programs. Given that most of the offshore funds were invested in liquid U.S. fixed-income securities, one might expect that after repatriation the top 15 cash holders sold some of these securities. The evidence supports this hypothesis: Figure 5 plots the net purchase of securities (scaled by assets)12 and shows that, indeed, after years of continuous net purchases of securities, the top 15 cash holders turned into net sellers in 2018. The top 15 cash holders sold about $115 billion of securities in 2018.13 The sales were strongest in 2018:Q1 ($66 billion or 3 percent of total assets) and continued throughout 2018 albeit at a slower pace, which is consistent with the pace of repatriation shown in figure 1.

Note: For years before 2015, annual averages of quarterly values are shown.

Source: Compustat; Bloomberg.

References

Dhammika Dharmapala, C. Fritz Foley, and Kristin J. Forbes (2011), "Watch What I Do, Not What I Say: The Unintended Consequences of the Homeland Investment Act," Journal of Finance, vol. 66 (June), pp. 753–87.

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs U.S. Senate (2011), "Repatriating Offshore Funds: 2004 Tax Windfall for Select Multinationals".

Zoltan Pozsar (2018), "Repatriation, the Echo-Taper and the €/$ Basis," Global Money Notes #11 (New York: Credit Suisse, January).

1. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. We thank Daniel Beltran, Carol Bertaut, Stephanie Curcuru, Thomas Laubach, Steve Sharpe, Michael Palumbo, and Beth Anne Wilson for comments and suggestions. Nathanael Coffey, Stephen Paolillo, Zach Fernandes, and Katie Rha provided excellent research assistance. The views in this document do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve System, its Board of Governors, or staff. Return to text

2. Cash held abroad is estimated by Board staff based on Bloomberg data for nonfinancial S&P 500 firms and refers to cash and cash equivalents, which include both cash and liquid assets held abroad and excludes overseas profits that are permanently reinvested in the companies' overseas operations. Estimates suggest that most of the cash held abroad is invested in dollar-denominated fixed-income assets (see Pozsar (2018)). Return to text

3. This transition tax is detailed in Section 965 of the TCJA. The one-time tax rate is 15.5 percent on liquid assets and 8 percent on illiquid assets. For comparison, the TCJA lowered the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. Return to text

4. The HIA provided a one-time reduction in the tax rate on repatriated earnings from the statutory rate of 35 percent to 5.25 percent for a one-year period in the November 2004 – December 2006 window. Most companies repatriated the funds in 2005 and a total of $312 billion were brought back that year by a total of 843 corporations, with the top 15 firms accounting for 52 percent of total repatriation (see U.S. Senate (2011)). Return to text

5. Under the pre-TCJA regime, using offshore funds for domestic investment or shareholder payouts would have been deemed a repatriation and thus subject to U.S. taxes. Return to text

6. Our analysis therefore examines the near-term effect associated with the repatriation of cash held abroad, and is not designed to speak to the broader effects of tax reform, which could also affect corporate financing patterns and investment. Return to text

7. Compustat data via Wharton Research Data Services, http://wrds.wharton.upenn.edu/. Dollar values shown above the red bars in Figs. 2 to 5 refer to the aggregate dollar value of the relevant variable (i.e., the numerator, without scaling by assets) for the top 15 cash holders. Return to text

8. Our previous note (https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/us-corporations-repatriation-of-offshore-profits-20180904.htm) covered only 2018:Q1, the latest available data at the time, showing no obvious increase in investment in the first quarter following the passage of the TCJA. Return to text

9. In terms of dollar values, investment in 2018 rose by 25 percent for the top 15 cash holders and by 10 percent for other nonfinancial S&P 500 firms. Return to text

10. This preliminary analysis does not capture other potential benefits of the corporate tax changes on aggregate investment expenditures. For example, it is possible that stock market investors redeploy the funds they receive from share repurchases to buy stocks in other firms that are pursuing capital expenditures. Return to text

11. The large drop in the debt-to-assets ratio in 2015:Q4 reflects GE's exit from GE Capital. Return to text

12. Net purchase of securities is defined as the purchase of securities minus the proceeds from the sale and maturity of securities. Return to text

13. Holdings of cash and short-term investments by the top 15 cash holders also fell by $110 billion from 2017:Q4 to 2018:Q4 (not shown). Together, the net sale of securities and the decline in cash and short-term investments therefore totaled $225 billion in 2018, roughly the amount spent on share buybacks. However, given the fungibility of money, and other cash inflows and expenses, one should be cautious in concluding that the decline securities and cash holding was solely used for the purpose of share buybacks. Return to text

Smolyansky, Michael, Gustavo Suarez, and Alexandra Tabova (2019). "U.S. Corporations' Repatriation of Offshore Profits: Evidence from 2018," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August 6, 2019, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2396.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.