FEDS Notes

July 14, 2022

Young Borrowers' Usage of Cosigned Credit Cards and Long Run Outcomes

Hannah Case1

In the United States, access to credit is an important channel for smoothing consumption and building wealth. However, establishing and building a credit history can take time. Parents may be able to help their children build credit early and ensure good credit behavior, such as paying on time, by being a cosigner on a credit card. That said, this is not an option for all young borrowers, which may result in unequal access to credit. Previous research on intergenerational credit has found that parents' credit scores are highly correlated with a child's future credit outcomes and that these outcomes may be due, in part, to unobserved differences between families (Ghent et al., 2016).

In this note, I explore the use of cosigned credit cards by parents to help their children establish and build credit. Unlike an individual credit card, a cosigned credit card requires another person, such as a parent, with income and good credit to guarantee that they will cover all balances if the cardholder does not make payments. In 2009, the CARD Act was passed, which significantly restricted access to credit cards for borrowers under 21 if they did not have a cosigner. Analyzing the effect of the CARD Act, Debbaut et al. (2016) found that borrowers who establish credit earlier are less likely to default and more likely to get a mortgage. Furthermore, previous work shows that entering the credit universe at a younger age is associated with a higher credit score by age 30 (Nathe, 2021). Using credit bureau data, I show that entering the credit universe with a cosigned credit card is associated with a higher credit score at the time of entry compared to entering with an individual credit card or another type of credit. Furthermore, I show that this gap in credit score persists as borrowers age and that borrowers with cosigned credit cards are more likely to have a mortgage by the time they are 30. Because the credit market experience plays a significant role in wealth accumulation, help from parents in building a strong credit history at a young age may be another channel that helps account for the correlations between parental and child wealth (Charles and Hurst, 2003).

Data and Methodology

I use the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel, hereafter called the CCP, which is a longitudinal panel that follows a 5% random and anonymized sample of borrowers with a credit file, called primary sample members as well as individuals living at the same address as a primary sample member. To study how parents and children use joint credit cards, I construct families by only keeping households with fewer than 6 people and defining a parent as someone in the household who is 18 to 45 years older than a child. When more than one individual in the household fits the criteria for a parent, I keep the two oldest. Since birth years and not exact birthdates are available in the data, I follow the method used by Debbaut et al. (2016), who use only data from December of each year to ensure that the age of borrowers is accurate. The dataset contains information on credit history, age, and geographic location for everyone in the dataset.

My analysis focuses on young borrowers who entered the credit universe from 2009 to 2014 between the ages of 18 and 20 and can be linked to at least one parent. Examining the period after the passage of the CARD Act in 2009 allows me to focus on a time period which increased the barriers to obtaining a credit card for young borrowers. Debbaut et al. (2016) have shown the existence of anticipatory effects between the passage of the bill and the date the bill when into effect in February 2010. Throughout my analysis, I focus on borrowers who enter the credit universe with different types of credit cards: cosigned, individual, or none. The CCP does not include information on whether a borrower is an authorized user which can effect a borrower's average age of credit.

Summary Statistics

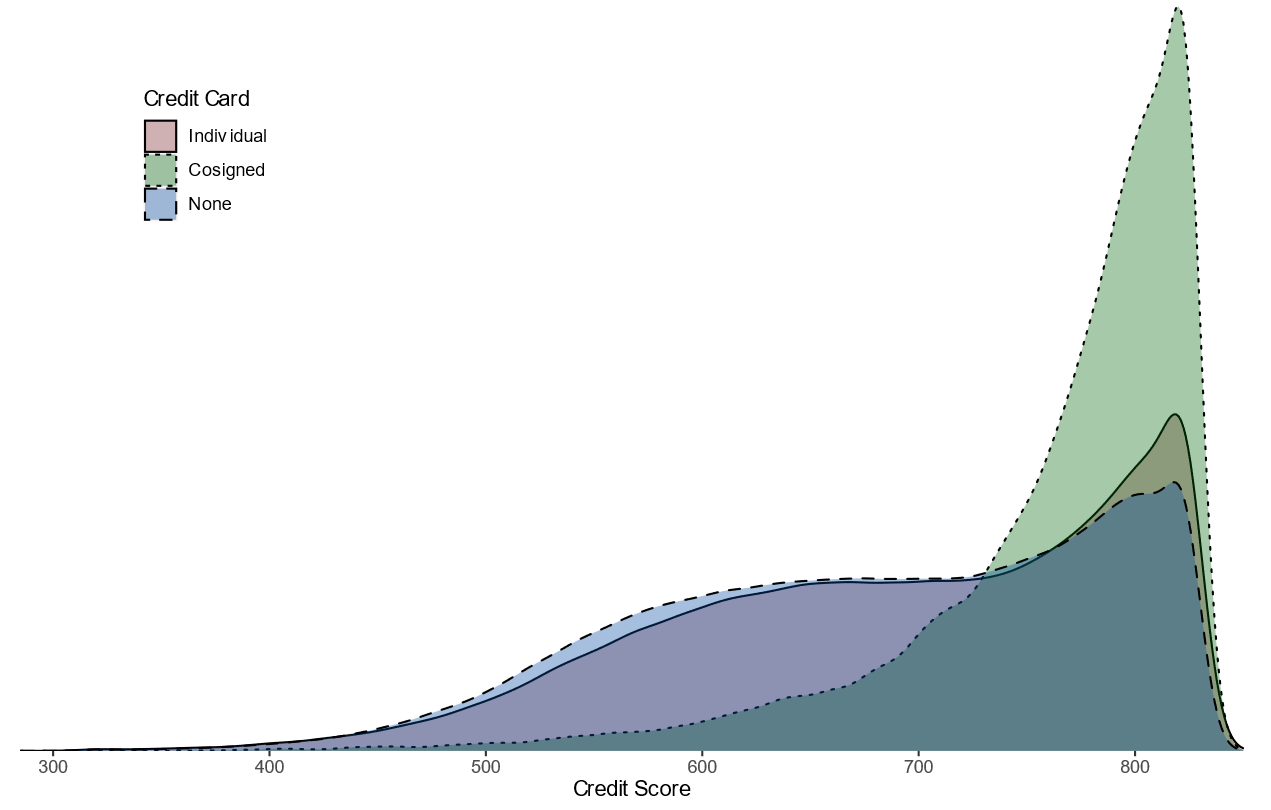

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the children in my sample at the time of their entry into the credit bureau data. 3.7% of children enter the credit universe with a cosigned credit card, 29.9% of children enter the credit universe with an individual credit card, and 66.4% of children enter the credit universe with no credit card. On average, young borrowers with cosigned credit cards, have higher Equifax Risk Scores, have parents with higher Equifax Risk Scores, and live in census tracts with a higher median income than young borrowers with individual credit cards or no credit card. In Figure 1, I further examine the credit distributions of the parents of young borrowers. The credit score distribution of the parents of young borrowers with cosigned credit cards skews to the left and a larger share of these parents have a higher credit score, relative to parents of borrowers with an individual credit card or no credit card at all. Together, these findings suggest that there are underlying differences between young borrowers who have cosigned credit cards and those who do not.

Table 1. Summary Statistics of Borrowers at Time of Entry

| Credit Card Type | Age | Risk Score | Parents’ Risk Score | Census Tract Income | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosigned | 19.1 | 686.3 | 760.2 | $77,300 | 3.7 |

| Individual | 19.3 | 641.7 | 685.9 | $68,431 | 29.9 |

| None | 19.1 | 642 | 674.2 | $63,593 | 66.4 |

Cross-Sectional Results

Next, I estimate the differences in credit score at time of entry in a multivariate format and examine their drivers. In column 1 of Table 2, I regress credit score on the type of credit card. Similar to Table 1, column 1 of Table 2 shows that borrowers with a cosigned credit card have a credit score 42 points higher than borrowers with an individual credit card and 46 points higher than borrowers with no credit card. As shown previously in Table 1, borrowers who start building their credit history with a cosigned credit card seem to differ from those who do not get a cosigned card. To assess whether some of these differences are driven by observable characteristics, I control for parental credit score, census tract, and year, in column 2 of Table 2. Controlling for these variables decreases the difference between borrowers with cosigned credit cards and individual credit cards by 11 points, and it decreases the difference between borrowers with cosigned credit cards and no credit card by 15 points.

Table 2. Credit Score at Time of Entry

| All | Parents Can Cosign | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit Card: Individual | -42.06*** | -30.79*** | -22.04*** | -21.36*** |

| (0.338) | (0.330) | (0.260) | (0.275) | |

| Credit Card: None | -46.35*** | -31.43*** | -42.55*** | -40.97*** |

| (0.333) | (0.324) | (0.255) | (0.268) | |

| Parent Risk Score: Near Prime | n.a. | -13.16*** | n.a. | n.a. |

| n.a. | (0.139) | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Parent Risk Score: Subprime | n.a. | -34.88*** | n.a. | n.a. |

| n.a. | (0.149) | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Constant | 689.8*** | 689.7*** | 698.6*** | 697.6*** |

| (0.324) | (0.315) | (0.241) | (0.253) | |

| Observations | 917,322 | 912,760 | 384,672 | 374,656 |

| R-squared | 0.021 | 0.219 | 0.105 | 0.257 |

| Census Tract FE | n.a. | Yes | n.a. | Yes |

| Year FE | n.a. | Yes | n.a. | Yes |

I then repeat the analysis using the subset of borrowers whose parents should be able to cosign a credit card. These are children of parents with prime credit scores and at least one credit card. In column 3, I repeat the analysis of column 1 using the subset of borrowers who have at least one parent who could be a cosigner. The results show that the difference in credit score between borrowers with a cosigned credit card and individual credit card or no credit card decreases by 20 points and 4 points respectively when comparing the results to those in column 1. These results suggest that some of the credit score gap, especially for those with individual credit cards, is in part due to differences in who can access a cosigned credit card. In column 4, I regress credit score on the type of credit and include census tract and year fixed effects, and the results remain essentially unchanged. Overall, these results suggest that having a cosigned credit card is associated with a higher credit score at the time of entry and that these differences cannot be fully explained by parental creditworthiness, year of entry, census tract, or access to cosigned credit cards.

Changes in Credit Outcomes over Time

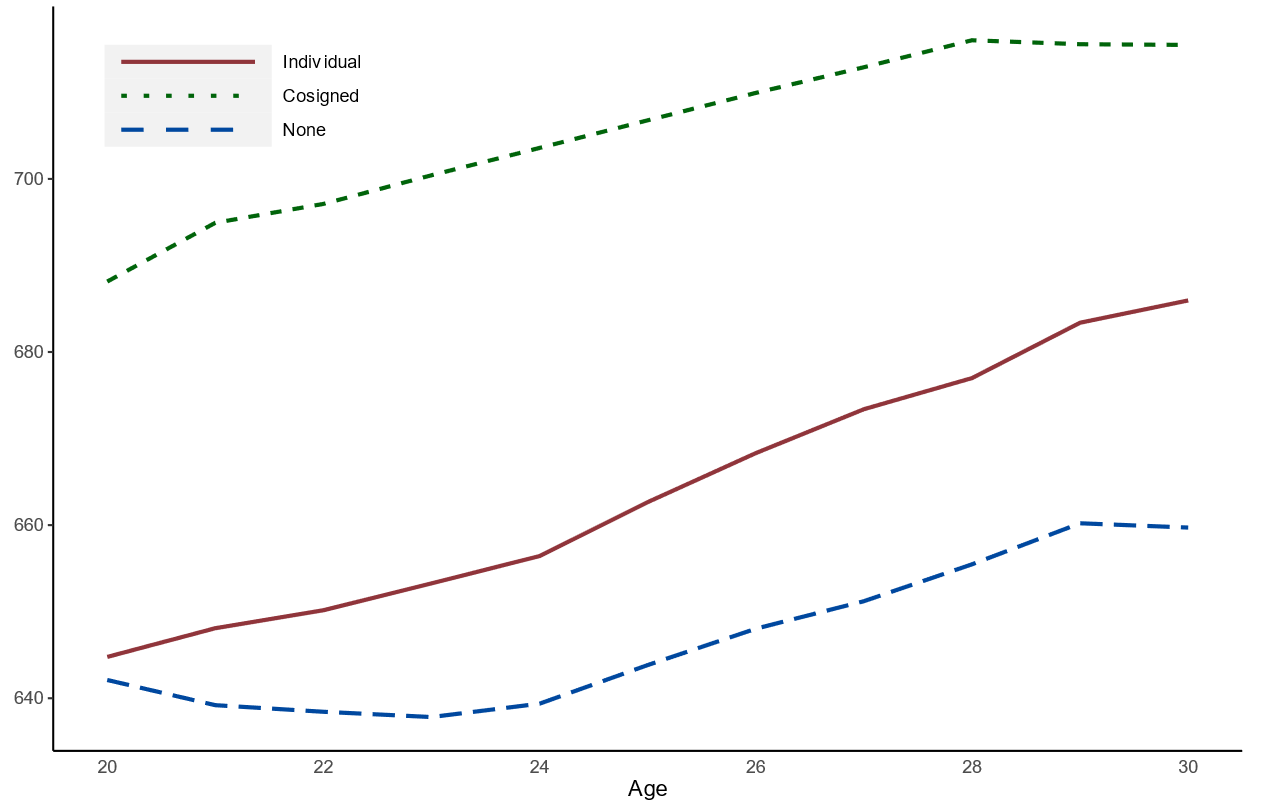

Having established that having a cosigned credit cards is associated with a higher credit score at the time of entry, I next examine how a borrower's credit score changes over time based on whether they have a cosigned card. Figure 2 plots the average credit score of borrowers from 20 to 30 years old based on whether they entered the credit universe with a cosigned credit card, individual credit card, or no credit card. By age 30, starting off with a cosigned credit card is associated with a 29-point higher credit score than having an individual credit card and over a 55-point higher credit score than young borrowers with no credit card.

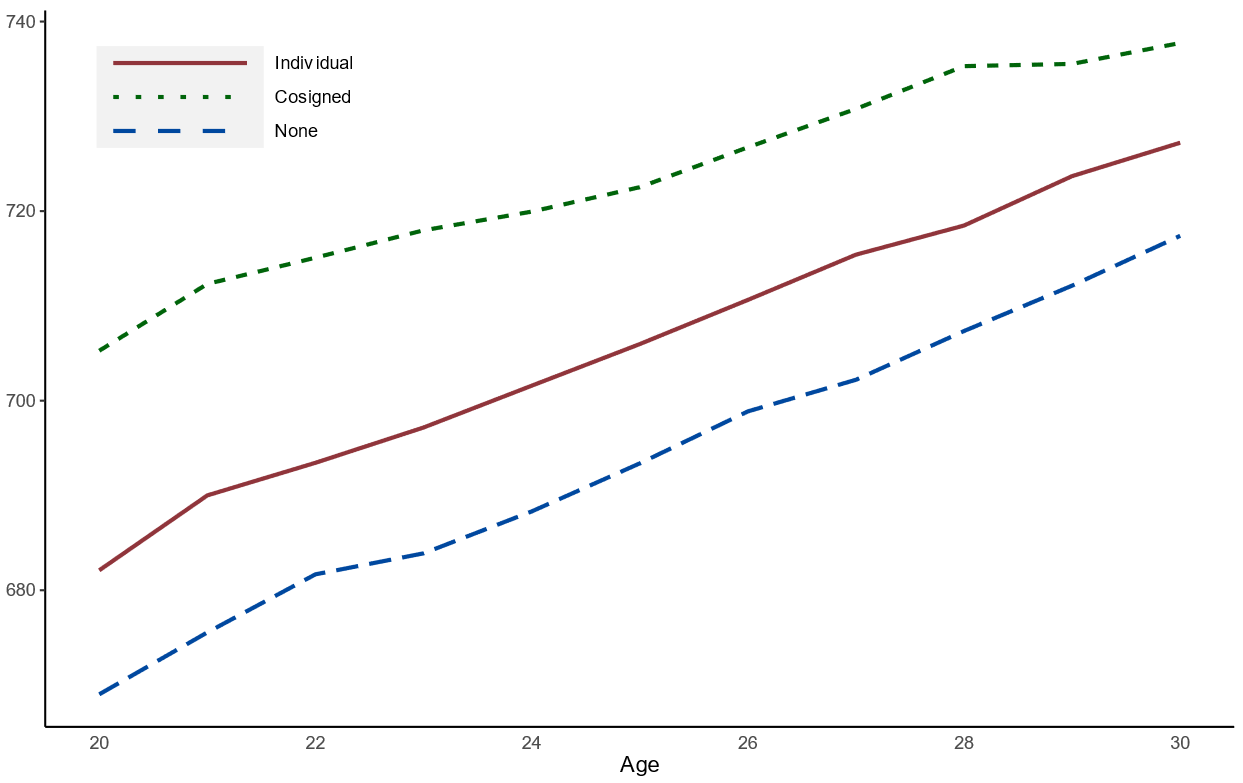

To further understand if these differences are in part driven by access to cosigned cards, in Figure 3, I examine the changes in credit score as borrowers age, only including children whose parents have a credit card and have a prime credit score. Figure 3 shows that there is still a persistent gap over time between the credit scores of young borrowers with cosigned credit cards and individual credit cards or no credit cards but that the gap is smaller than in the full sample of young borrowers.

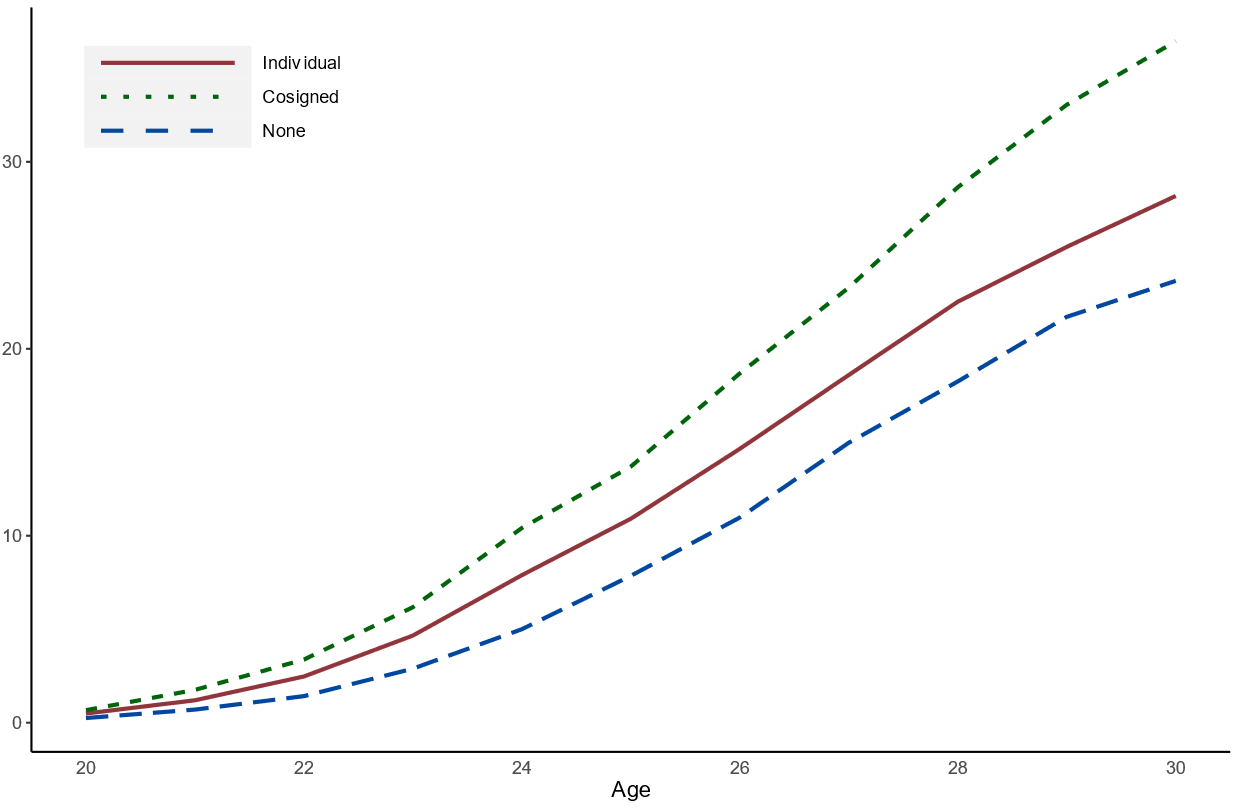

Given the persistence of these differences, I next examine whether they may lead to differences in access to credit. For example, in the United States, having a sufficiently good credit score is necessary to be approved for a mortgage. In addition, credit for less creditworthy borrowers generally comes with higher interest rates, which may reduce a borrower's ability to access affordable credit. To address this question, in Figure 4, I plot the percent of young borrowers who have a mortgage over time. The figure shows that by age 30, young borrowers who had a cosigned credit card are 8.3 percentage points and 13 percentage points more likely to have a mortgage than those with an individual credit card or no credit card respectively, suggesting that borrowers who enter the credit universe with a cosigned credit card are more likely to be homeowners by the time they are 30.

Conclusion

In this note, I show that entering the credit universe with a cosigned credit card is associated with a higher credit score and higher likelihood of having a mortgage as borrowers age. Access to a cosigned credit card depends, in part, on having a parent or other borrower with a good credit history, and so this suggests that parents with high credit scores and access to credit may be able to help their children build and establish credit. At the same time, a parent's ability to cosign a card is likely correlated with other aspects of a borrower's financial life such as financial literacy, income, and other assets. Further work may help shed light on whether having a cosigned credit card has a causal effect on access to credit later in life. In addition, the use of authorized cards, which may allow parents to have a more direct impact on their children's credit score, is also an important topic for further analysis.

Citations

Charles, Kerwin Kofi, and Erik Hurst. (2003). "The correlation of wealth across generations." Journal of political Economy 111, no. 6, 1155-1182.

Debbaut, P., Ghent, A., & Kudlyak, M. (2016). "The CARD act and young borrowers: The effects and the affected", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 48(7), 1495-1513.

Ghent, Andra C., Marianna Kudlyak (2016). "Intergenerational Linkages in Household Credit", Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2016-31.http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/wp2016-31.pdf

Nathe, Lucas (2021). "Does the Age at Which a Consumer Gets Their First Credit Matter? Credit Bureau Entry Age and First Credit Type Effects on Credit Score," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July 09, 2021.

1. I thank Vitaly Bord, Geng Li, Alvaro Mezza, and Kamila Sommer for their valuable guidance, encouragement, and comments. The views presented here are those of the author's and do not represent those of the Federal Reserve Board or its staff. Return to text

Case, Hannah (2022). "Young Borrowers' Usage of Cosigned Credit Cards and Long Run Outcomes," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July 14, 2022, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3165.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.