FEDS Notes

November 05, 2021

Caregiving for children and parental labor force participation during the pandemic

Joshua Montes, Christopher Smith, and Isabel Leigh

The labor force participation rate (LFPR)—the fraction of the population ages 16 and older that is either working or actively looking for work—moved up steadily over the last few years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and stood at 63.3 percent in February 2020. Two months later, the LFPR had plunged to 60.2 percent, and despite some improvement since then, the LFPR has remained depressed relative to its pre-COVID level (fluctuating between 61.4 percent and 61.7 percent since Fall 2020).

Although there are likely many reasons why the LFPR has fallen and remains low, a key concern has been the role of caregiving, especially in light of the lack of in-person learning for many students during much of the pandemic. One way of assessing how caregiving burdens have weighed on the LFPR is by examining self-reported reasons for being out of the labor force as reported in the Current Population Survey (CPS), and in particular, examining changes in the population that report being out of the labor force and primarily engaging in caregiving activities relative to pre-pandemic levels.

In this Note, we show that caregiving burdens appear to have weighed substantially on labor force participation rate during the pandemic. To identify caregiving burdens among nonparticipants in the labor force, we classify "nonparticipation due to caregiving reasons" as those respondents who indicate being out of the labor force and whose primary activity is "taking care of the house or family," which we interpret as including caregiving responsibilities for either children or adults.1 Of course, people's labor force participation decisions are complex and weigh a number of concerns and influences which may be difficult to fully capture in the CPS.2 Consequently, some people who report being out of the labor force and are primarily engaged in caregiving may have other reasons that would prevent their labor force participation even if caregiving concerns were resolved. Nevertheless, we think self-reported, primary activities among nonparticipants provide useful insights into the importance of factors that are currently depressing labor force participation relative to pre-pandemic levels. Our assumption is that people are reporting, as best they can, the primary reason for why they are not currently participating in the labor market. Later in this Note we provide evidence that the increase in parents' nonparticipation for caregiving concerns (especially among mothers), as well as the difference in employment-to-population ratios (EPOPs) and LFPRs between mothers and non-mothers, appear consistent with the monthly pattern of children's remote and in-person education during much of the pandemic–lending further credibility to using nonparticipation due to caregiving as a measure of the impact of caregiving concerns on labor force participation.

Table 1. Change in the labor force participation rate and select contributions, February 2020 to August 2021

| Change (percent of population age 16 and older), in percentage points: | |

|---|---|

| 1. Labor force participation rate | -1.5 |

| 2. Out of the labor force for caregiving reasons | 0.4 |

| 3. Parent only with children age 5 or younger in the household | 0.0 |

| 4. Parent with at least one child age 6 to 17 in the household | 0.1 |

| 5. Do not have own children age 17 or younger in the household | 0.3 |

| 6. Out of the labor force, all other reasons | 1.1 |

Note: Table shows the change in the percent of the population age 16 and older who report being in the labor force (line 1), out of the labor force for caregiving reasons (lines 2 through 5), and out of the labor force for all other reasons (line 6). Lines 3 through 5 show the change in the percent of the population out of the labor force for caregiving reasons and who have children in the given ages or with or without children age 17 or younger (lines 4 to 6). Lines 2 and 6 sum to line 1, and lines 3 to 5 sum to line 2. See text for definition of caregiving reasons.

Source: Authors’ estimates from publicly available microdata to the Current Population Survey. Seasonally adjusted by authors.

The share of the population reporting as not participating in the labor market due to caregiving reasons has increased by 0.4 percentage point from February 2020 to August 2021, accounting for about one-third of the overall decline in the LFPR over this period (see Table 1).3 Of this increase, about 0.1 percentage point (line 4) is attributable to parents with school-age children (age 6 to 17)—a small drag on the aggregate LFPR.4 Also, as shown in line 5 of table 1, caregiving burdens since the onset of COVID-19 extend beyond parents with school age children, as the increase in nonparticipation for caregiving reasons among nonparents accounts for about 0.3 percentage point of the aggregate increase.

Comparing only current outcomes to pre-pandemic levels, though, ignores substantial variation over time and across various subgroups of the population. The focus of this note is to explore in more detail the increase in nonparticipation for caregiving concerns across those and other dimensions. We highlight three key observations:

1) Although caregiving concerns among parents and nonparents currently account for around one-third of the decrease in the aggregate LFPR, increased caregiving burdens appear to account for more than three-quarters of the decline in the LFPR of mothers with school-aged children since February 2020 and one-third of the decline for fathers with school-aged children.5

2) Parents' nonparticipation for caregiving reasons was more elevated in fall 2020 and that winter, contributing about 0.4 percentage point to the decline in the aggregate LFPR over that time, and has declined since. This pattern is consistent with widespread closures of K-12 schools to in-person learning in that fall and subsequent reopening of many school districts in the spring.

3) Nonparticipation for caregiving reasons has been especially elevated for Black and Hispanic mothers, generally two to three times as large as caregiving concerns among white mothers and remain more elevated than white mothers through the second quarter of 2021. This pattern may in part reflect that virtual education was disproportionately concentrated in school districts where the majority of students were either Black or Hispanic.6

Parents' nonparticipation since the start of the pandemic

Differences between parents with school-age children and other adults

The LFPRs for parents are substantially below levels in February 2020—2.1 percentage points lower for mothers and 0.4 percentage point lower for fathers (see Table 2, first column, line 1 for mothers and line 2 for fathers). The increase in nonparticipation for caregiving reasons (Table 2, second column) accounts for three-quarters of the decline in labor force participation for mothers and about half of the decrease for fathers. Despite the large increase in parents' nonparticipation for caregiving concerns, the impact on the aggregate LFPR is more modest because parents comprise less than 25 percent of the total population—about 13 percent for mothers with children up to age 17 and 10 percent for fathers. In comparison, nonparticipation among women and men without children due to caregiving increased only 0.3 percentage point and accounts for 20 percent of their overall decline in labor force participation (line 3).7

Table 2. Change in the labor force participation rates and the rates of nonparticipation due to caregiving reasons, by parental status and children’s ages, February 2020 to August 2021

| For each group, the change in their: Labor force participation rate | For each group, the change in their: Share not in the labor force for caregiving reasons | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Women, age 16 and older | -1.6 | 0.4 |

| 2. Men, age 16 and older | -1.3 | 0.4 |

| 3. Women and men without children | -1.4 | 0.3 |

| 4. Parents only with children age 5 and younger | -0.8 | 1.1 |

| 5. Parents with at least one child age 6 to 17 | -1.3 | 0.9 |

| 6. Mothers with at least one child age 6 to 17 | -1.8 | 1.4 |

| 7. Fathers with at least one child age 6 to 17 | -0.6 | 0.2 |

Note: Table shows the change in the percent of each group that reports being in the labor force (column 1), and the change in percent of each group that reports being out of the labor force with caregiving as their primary activity (column 2). See text for definition of caregiving reasons.

Source: Authors’ estimates from publicly available microdata to the Current Population Survey. Seasonally adjusted by authors.

The modest effect of parents' caregiving burdens in the aggregate shown earlier in Table 1 masks substantial variation among parents. As shown in the bottom panel of Table 2, from February 2020 to August 2021, nonparticipation owing to caregiving burdens as a share of the population increased by 1.1 percentage point for parents with only children younger than 6 years old (line 4, column 2) and 0.9 percentage point for parents with at least one "school-age" child between the ages of 6 and 17 years old (line 5, column 2). Those changes in nonparticipation due to caregiving account for nearly all or more than all of the decrease in labor force participation for these groups.8

Through the rest of this Note, we focus primarily on labor force participation for parents with school-age children, given interest among policymakers about how the widespread lack of in-person K-12 education during much of the 2020-2021 school year and resumption of in-person education to most students in fall 2021 may have affected parental labor force participation. Within this group, the decline in labor force participation has been much larger for mothers with at least one school-age child than for fathers and the increase in nonparticipation for caregiving accounting for most of the difference: nonparticipation for caregiving has increased 1.4 percentage points for mothers (line 6, accounting for more than three-quarters of the decline in their LFPR) but increased only 0.2 percentage point for fathers (line 7, accounting for one-third of the decline in their LFPR).

Changes in nonparticipation for caregiving reasons for parents since the start of the COVID pandemic

The comparison of changes in LFPRs and nonparticipation for caregiving reasons between early 2020 and now, as in Tables 1 and 2, potentially overlooks any important variation in these measures over this period. For example, caregiving burdens may have been more substantial earlier in the pandemic when more K-12 schools were closed to in-person education and some daycare facilities were closed. To explore how LFPRs and nonparticipation for caregiving have evolved over the course of the pandemic, we compare measures of nonparticipation for a particular month to the same pre-COVID calendar month (for most of the analysis we use the same calendar month in 2019 as our comparison).9 We focus on parents between the ages of 25 and 54 since this is the group much more likely to have school-age children than are adults age 55 and older or 24 and younger.

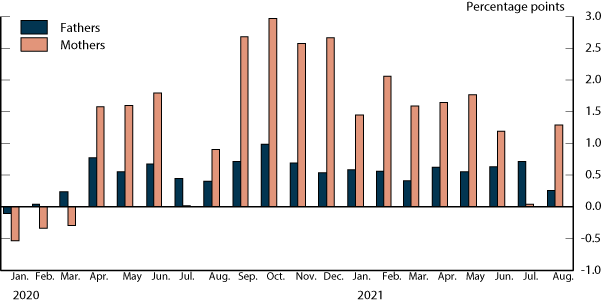

Figure 1. Parents age 25-54 with school-age children who report being out of the labor force for caregiving reasons, relative to same month in 2019

Note: Figure shows the change in the percent of mothers and fathers with at least one child age 6 to 17 that report being not in the labor force with caregiving as their primary activity, for the given month relative to the same calendar month in 2019. Key identifies bars in order from left to right.

Source: Authors' estimates from publicly available microdata to the Current Population Survey.

Parents of school-age children have reported sharp increases in rates of being out of the labor force for caregiving reasons in nearly every month since the start of the pandemic compared to the same months in 2019, with the largest increases occurring in September through December 2020 (see figure 1).

- For mothers, nonparticipation for caregiving reasons has been substantially elevated during school-year months, relative to the same 2019 calendar month, especially in the fall and winter of the 2020-2021 school year:

- From April through June 2020, nonparticipation for caregiving was more than 1 1/2 percentage points higher compared to the same months in 2019, consistent with the initial closure of essentially all K through 12 schools to in-person learning at the onset of the pandemic.

- During June and July 2020, caregiving burdens were not much higher than for the same months in 2019, reflecting that, prior to the pandemic, there was typically an increase in the percent of mothers who reported being out of the labor force due to caregiving during the months when children are usually out of school on summer vacation.

- From September through December 2020, nonparticipation for caregiving was elevated 2 1/2 percentage points to 3 percentage points—its peak increase during the pandemic.

- Over the first half of 2021, nonparticipation due to caregiving declined some but remained elevated around 1 1/2 percentage points relative to the same months in 2019.

- In July 2021, nonparticipation for caregiving was little different than in 2019, similar to July 2020.

- Finally, in August 2021, this measure of nonparticipation moved back up and was nearly 1 1/2 percentage points above August 2019.

- For fathers, nonparticipation for caregiving reasons has been around 1/2 percentage point above 2019 levels through much of the pandemic.10

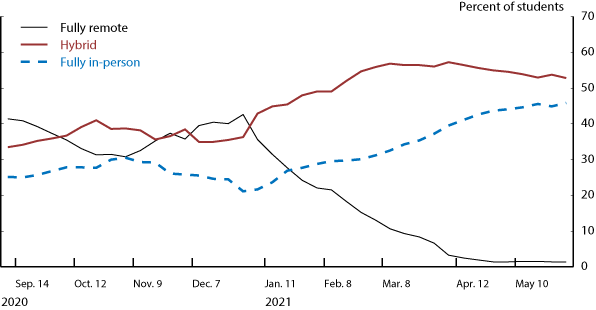

Figure 2. Percent of students in public school districts that provide fully remote, fully in-person, or hybrid education

Note: Figure shows the percent of public school students in grades K to 12 that were estimated to be in districts that were fully remote, fully in-person, or in districts where a choice was provided or a hybrid approach was used.

Source: Authors' estimates from data provided by the American Enterprise Institute's Return To Learn Tracker.

The pattern of nonparticipation for caregiving reasons for mothers with school-age children over the 2020-2021 school year—peaking in September through December 2020 and coming down in 2021—is consistent with the evolution of remote and in-person education over this period. To illustrate this point, we use data from the American Enterprise Institute's Return To Learn tracker, which provides a weekly estimate of the number of students who are in districts that offer in-person education to all students, remote education to all students, or a hybrid of remote and in-person learning. Using these data, we plot estimates of the fraction of students in districts under each of the three education types (see figure 2).11 The fraction of students who were in districts that offered only remote education peaked in the winter at about 40 percent and fell to around 1 percent by April. As remote education declined in Spring 2021, fully in-person or hybrid learning environments became more common. The concurrent decline in remote education and decline in parents' nonparticipation for caregiving reasons lends credibility that this measure of nonparticipation for caregiving reasons is capturing the impact of children's virtual education on parents' labor supply.

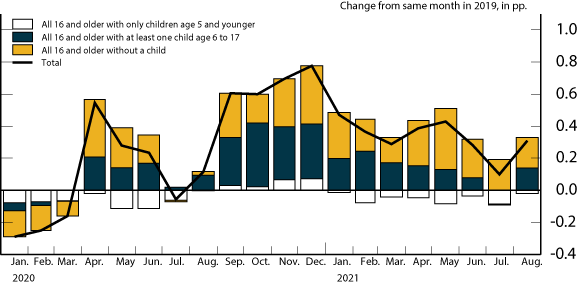

Note: The black line in the figure shows the increase in the fraction of the population age 16 and older that reported being out of the labor force with caregiving as their primary activity, for the listed calendar month relative to the same month in 2019. The white, dark blue, and orange bars show the amount of the total change in caregiving attributable to particular groups; the three colored bars sum to the black line.

Source: Authors' estimates from publicly available microdata to the Current Population Survey.

The black line in figure 3 shows the increase in nonparticipation for caregiving reasons for all individuals age 16 years and older relative to the same month in 2019. This increase is then apportioned into the amount attributable to the increase in nonparticipation for caregiving from: 1) those only with children age 5 and younger (white bars); 2) those with any children between the ages of 6 and 17 (dark blue bars); 3) those without children (orange bars). For most months, the increase in all forms of caregiving relative to 2019 is attributable to an increase in nonparticipation from parents with children age 6 to 17 and to nonparents; the increase attributable to parents with only younger children is negligible, or for some months, negative.

The increase in nonparticipation for caregiving reasons attributable to parents with school-age children peaked around 0.4 percentage point in the winter but declined to about 0.2 percentage point, on average, in the spring, consistent with the pattern in fully remote and fully in-person learning since September 2020, as discussed above. For nonparents, the contribution from caregiving to the decline in the aggregate LFPR has been relatively stable since the start of the pandemic, averaging about 1/4 percentage point per month, with some month-to-month fluctuations around that level. Overall, these estimates are consistent with the impact of caregiving burdens on labor force participation peaking in the winter (especially for parents) and coming down some through the spring. If most of the increase for parents with school-age children is attributable to the lack of in-person education for their children (and ignoring any effect on the labor force participation of nonparents), then the closure of many schools to in-person education held down the aggregate LFPR by 0.4 percentage point in the end of 2020 and around 0.2 percentage point in the first half of 2021. The effect of virtual learning on the aggregate labor force participation rate could be somewhat larger, since some of the caregiving-related increase in nonparticipation for nonparents also likely reflects in caregiving for school-age children that were not learning in person.

Differences between mothers and other women

Although the labor force participation decisions of mothers and non-mothers may differ for a variety of reasons and be associated with a complex set of characteristics—only some of which may be directly observable in the CPS and controlled for when comparing the evolution of labor market outcomes for parents to nonparents—we nonetheless find it informative to compare the evolution of LFPRs and EPOPs since the start of the pandemic for mothers relative to non-mothers.

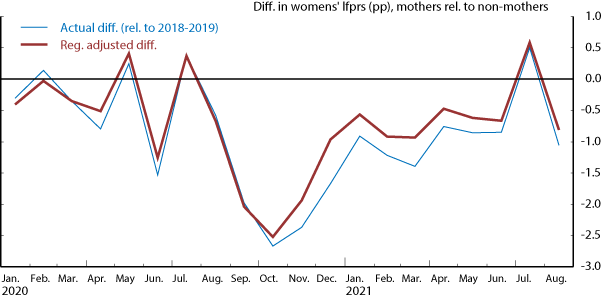

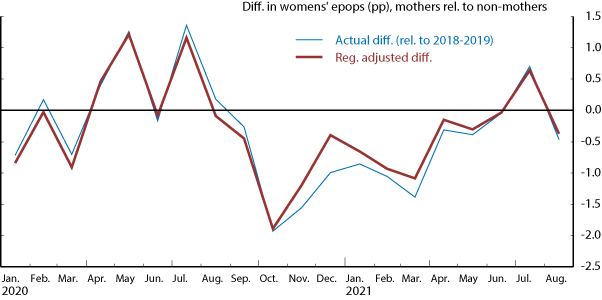

We take two approaches to compare the evolutions of LFPRs and EPOPs between parents and nonparents. First, we simply calculate the gap in LFPRs and EPOPs between parents and nonparents for each month since the start of the pandemic. Then, we calculate the difference between those gaps and the average pre-pandemic gap from 2018 to 2019 for the same calendar month. Thus, we compare the mother/non-mother LFPR and EPOP gaps for each month since the start of the pandemic relative to the same calendar month over a multi-year pre-pandemic period. Second, we estimate a person-level linear probability model for all women ages 25 to 54 from 2018 through June 2021 on a series of monthly COVID indicator variables (one for each month from March 2020 through August 2021), an indicator variable for whether a woman is a mother of a school-age child, the interaction of the monthly COVID indicator variables and the indicator for being a mother of a school-age child, and other observable characteristics.12 The estimated coefficients on the interactions of the monthly COVID indicators and the indicator for being a mother of a school-age child yield monthly estimates of the gap between mothers' and non-mothers' LFPRs and EPOPs after controlling for observables. The blue line in Figures 4A and 4B shows the unadjusted difference in the LFPR and EPOP for parents relative to nonparents, and the red line shows the difference after controlling for observable differences in the regression.13

Figure 4. Gap in LFPR and EPOP between mothers and non-mothers, relative to the same pre-COVID month

B. Employment-to-population ratio

Note: The blue line in the figures show, for women age 25 to 54, the gaps between the labor force participation rates and employment-to-population ratios for mothers with at least one child age 6 to 17 relative to women without children, for the given month relative to the average of the same month in 2018 and 2019. The red line shows the difference after adjusting for observable characteristics as listed in the text; it plots the coefficients from a linear probability regression of labor force participation or employment on indicator variables for the months listed in the figure interacted with an indicator for having a child age 6 to 17, using the sample of all women age 25 to 54 in 2018 to 2021. See text for more details.

Source: Authors' estimates from publicly available microdata to the Current Population Survey.

The month-by-month pattern of differences in LFPRs and EPOPs (relative to the same pre-COVID month) between mothers and non-mothers is consistent with a substantial drag from virtual schooling and related caregiving concerns in the fall and winter on the employment and labor force participation of mothers. In the early months of the pandemic (March through August 2020), the EPOPs for mothers and non-mothers moved by roughly similar amounts, on average, whereas the LFPR was slightly lower on average for mothers. Around September 2020, however, the LFPR and EPOP for mothers declined substantially relative to non-mothers, before improving relative to non-mothers in spring 2021. This pattern corresponds to when mothers' nonparticipation for caregiving was especially elevated (Figure 1) and may suggest that, after stay-at-home orders were lifted in the summer and economic activity started to rebound in the fall, nonparents were able to return to the labor force and become re-employed to a greater degree than were parents, for whom caregiving concerns became the binding constraint. Similarly, the relative improvement since the winter is also consistent with easing of childcare related concerns as in-person education became more common in the spring.14 Despite this improvement, in spring 2021 and more recently in August 2021, the difference in the EPOP and LFPR for mothers with school-age children relative to women without children was substantially larger than in the same months prior to COVID, even after adjusting for observable characteristics.

The monthly pattern illustrated in figures 4A and 4B also illustrate that a comparison of spring 2021 to a pre-COVID period misses the steep decline in labor market outcomes for mothers relative to other women in the fall and winter. For example, the regression adjusted difference in LFPRs between mothers with school age children and non-mothers (relative to the same pre-COVID calendar month) widened by 0.5 percentage point between the first quarters of 2020 and 2021, but by 1.5 percentage points between the first quarter and the fourth quarter of 2020. Similarly, the increase in the EPOP gap between mothers and non-mothers widened by 0.3 percentage point between the first quarters of 2020 and 2021, but by 0.6 percentage point between the first quarter and fourth quarter of 2020.

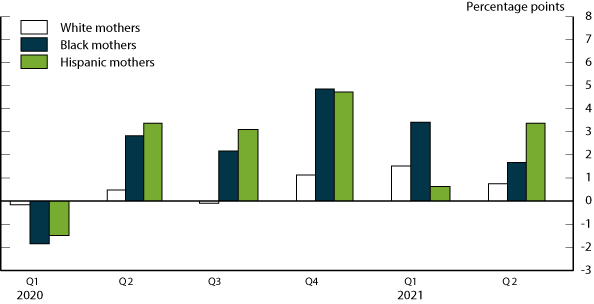

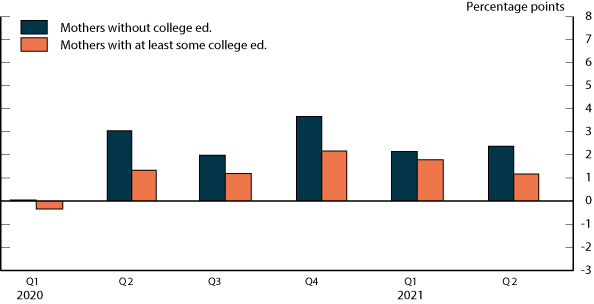

Differences in nonparticipation for caregiving concerns by mother's race, ethnicity, and education

While caregiving concerns since the start of the pandemic appear to have had a significant impact on mothers' labor force participation overall, there is also significant heterogeneity by mothers' race, ethnicity, and educational attainment. Nonparticipation due to caregiving has been substantially more elevated for Black and Hispanic mothers than for white mothers (Figure 5A), especially in the fourth quarter of 2020, when it was elevated by nearly 5 percentage points for Hispanic and Black mothers, but just over 1 percentage point for white mothers. Differences relative to white mothers have converged some over the first half of 2021. Similarly, nonparticipation for caregiving increased more for mothers without a college education relative to mothers with at least some college education (Figure 5B), especially in the fourth quarter of last year, and have narrowed somewhat over the first half of 2021. The LFPRs by mother's race/ethnicity and education have exhibited a similar pattern, declining more for Black and Hispanic mothers and mothers without a college education—with LFPR gaps widening in the fourth quarter of 2020 and narrowing somewhat in the first half of 2021.

Figure 5. Percent of mothers age 25-54 who report being out of the labor force for caregiving reasons (relative to same quarter in 2019)

Note: Key identifies bars in order from left to right.

Source: Authors' estimates from publicly available microdata to the Current Population Survey.

Note: This figure shows the change in the percent of mothers age 25 to 54 with at least one child between the ages of 6 and 17 and with the listed characteristics that report being not in the labor force with caregiving as their primary activity, for the given quarter relative to the same quarter in 2019. (Specifically, we calculate the deviation for each calendar month relative to the same calendar month in 2019, and then average for each quarter.) Key identifies bars in order from left to right.

Source: Authors' estimates from publicly available microdata to the Current Population Survey.

Although the racial and ethnic gap in LFPRs between Black and Hispanic women with white women tends to widen during recessions, the substantially larger decrease in Black and Hispanic women's LFPRs and larger increase in nonparticipation for caregiving reasons since the start of the pandemic may reflect factors specific to the pandemic instead of standard business cycle dynamics. First, Black and Hispanic mothers were more likely to be employed in industries most negatively impacted by the pandemic and for which tele-commuting is less likely, such as accommodation and food services, than were white mothers. For example, in 2019, roughly 5 percent of all white mothers were employed in the accommodation and food services industry, as opposed to about 7 percent of Black mothers and 13 percent of Hispanic mothers.

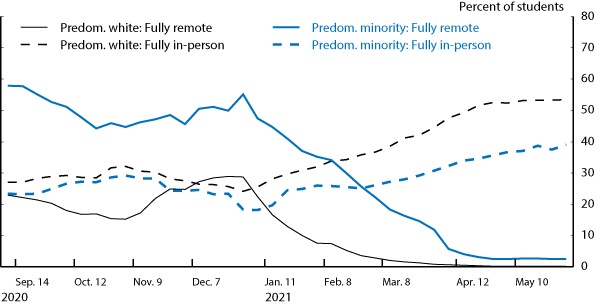

Figure 6. Percent of students in public school districts that provide fully remote or in-person education, for districts where students are predominantly white or predominantly minority

Note: Figure shows the percent of public school students in grades K to 12 that were estimated to be in districts that were fully remote, fully in-person, or in districts where a choice was provided or a hybrid approach was used. Predominantly white districts are those where at least 50 percent of students are white; predominantly minority districts are all other districts.

Source: Authors' estimates from data provided by the American Enterprise Institute's Return To Learn Tracker.

Additionally, public school districts that were predominantly non-white were more likely to have at least some remote learning in the fall, suggesting that the childcare burdens associated with virtual learning may have been more acute in Black and Hispanic communities for much of the 2020-2021 school year (see figure 6). From the winter of 2020/2021 through spring 2021, the percent of students in districts providing in-person education converged between predominantly white and predominantly nonwhite school districts, possibly consistent with the greater decline in nonparticipation for caregiving among Black and Hispanic mothers.

Summary and Looking forward

Since the start of the pandemic, nonparticipation in the labor force for caregiving reasons has been substantially elevated for mothers relative to pre-pandemic levels and accounts for most of the decline in mothers' labor force participation over this period. The increase in nonparticipation for this reason has been especially large for Black and Hispanic mothers, which may in part reflect differences in pre-COVID industry and occupation and the availability of in-person education for students. From the winter of 2020/2021 through spring 2021, the modest easing of nonparticipation for caregiving reasons and improvements in LFPR and EPOP for mothers (especially relative to non-mothers) appears consistent with the reopening of schools to in-person education having some positive effects on mothers' labor force participation over that period. Coincident with the resumption of in-person learning, the overall impact on the aggregate LFPR from parents' elevated levels of OLF-care declined from 0.4 percentage point at the end of 2020 to around 0.2 percentage point in spring 2021 and August 2021. Caregiving concerns more broadly—including those for nonparents—appear to have imparted a drag on the LFPR of 3/4 percentage point at the end of 2020 and around 0.4 percentage point for most of this year compared to before the pandemic.

Available data indicate that nearly all K-12 public school districts started the 2021-2022 school year offering full in-person education.15 However, even with a complete opening of schools to fully in-person learning in the fall, caregiving burdens are likely affecting parents' labor force participation decisions more than they were pre-pandemic. Young school-age kids will likely not be eligible for vaccinations until sometime in the fall or winter, and some schools have instituted restrictions on attendance if children exhibit cold-like symptoms or if classmates test positive for COVID-19. Consequently, some parents may face considerable uncertainty about whether their students will be learning in-person for the entirety of the school year and may be reluctant to re-enter the labor force until this uncertainty is resolved.16 In addition, some parents appear to have taken up their schools' offer of optional virtual education, which may also hinder some parents' return to the labor force. That said, if disruptions to in-person education do remain minimal in the fall, if parents become sufficiently convinced this will remain the case through the school year, and consequently if those who were not in the labor force in the spring due to caregiving concerns re-enter the labor force, the aggregate LFPR may increase relative to August due to an easing of caregiving burdens by roughly 0.2 percentage point (if all nonparticipating parents for caregiving reasons return to the labor force) to 0.4 percentage point (if all nonparticipating people for caregiving reasons return to the labor force).

References

Atkinson, Tyler, and Alex Richter. "Pandemic Disproportionately Affects Women, Minority Labor Force Participation." Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, blog post, November 10, 2020.

Bauer, Laren, Elian Buckner, Sara Estep, Emily Moss, and Morgan Welch. "Ten Economic Facts About How Mothers Spend Their Time." The Hamilton Project, Economic Facts, March 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Maternal_Time_Use_Facts_final-1.pdf

Boesch, Tyler, Rob Grunewald, Ryan Nunn, and Vanessa Palmner. "Pandemic Pushes Mothers of Young Children Out of the Labor Force." February 2, 2021. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis blog post. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2021/pandemic-pushes-mothers-of-young-children-out-of-the-labor-force

Furman, Jason, Melissa Kearney, and Wilson Powell. "The Role of Childcare Challenges in the US During the COVID-19 Pandemic." June 2021. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 28934. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28934/w28934.pdf

Heggeness, Misty. "Why is Mommy So Stressed? Estimating the Immediate Impact of the COVID-19 Shock on Parental Attachment to the Labor Market and the Double Bind of Mothers." October 2020. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Institute Working Paper 33, October 2020. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/institute-working-papers/why-is-mommy-so-stressed-estimating-the-immediate-impact-of-the-covid-19-shock-on-parental-attachment-to-the-labor-market-and-the-double-bind-of-mothers

Lim, Katherine and Mike Zabek. "Women's Labor Force Exits during COVID-19: Differences by Motherhood, Race, and Ethnicity." Forthcoming. Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Discussion Series.

Lofton, Olivia, Nicholas Petrosky-Nadeau, and Lily Seitelman. "Parental Participation in an Pandemic Labor Market." April 2021. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Economic Letter 2021-10. https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2021/april/parental-participation-in-pandemic-labor-market/

Luengo-Prado, Maria J. "COVID-19 and the Labor Market Outcomes for Prime-Age Women." April 2021. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Current Policy Perspectives, April 2021. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/current-policy-perspectives/2021/covid-19-and-the-labor-market-outcomes-for-prime-aged-women.aspx

Pitts, M. Melinda. "Where Are They Now? Workers with Young Children During COVID-19." Septembe 2021. Policy Hub No. 10-2021, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/research/publications/policy-hub/2021/09/01/10--where-are-they-now--workers-with-young-children-during-covid-19.pdf

Tuzeman, Didem. "Women Without College Degrees, Especially Minority Mothers, Face a Steeper Road to Recovery." Forthcoming. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review. https://www.kansascityfed.org/documents/8243/er21v106n3tuzemen.pdf

1. We use the "NLFACT" question in the CPS to measure the primary activity of nonparticipants. This question is asked of all respondents who report not being in the labor force. It specifically asks: "What best describes your current situation at this time? For example, are you disabled, ill, in school, taking care of house or family, or something else?" Respondents can choose any of those reasons, in addition to "in retirement." Return to text

2. Further, there may be other factors facilitating respondents' ability to stay out of the labor force and focus on caregiving which aren't captured in these survey responses, for example, income support from unemployment insurance or family savings. Return to text

3. The data used in Tables 1 and 2 are seasonally adjusted by the authors. The last month of available data at the time of writing was August 2021. The "out of the labor force, all other reasons" category includes retirements, disability, schooling, illness, and the catchall "other" category. Return to text

4. These estimates are qualitatively similar to those from Furman, Kearney, and Powell (2021), which concludes that the change in LFPRs and EPOPs from 2020Q1 to 2021Q1 between parents and non-parents was similar, after adjusting for observable differences, and thus that the current slow recovery in the EPOP and LFPR is unlikely to be due to parental nonparticipation. Return to text

5. For other analyses highlighting the steeper decline in labor force participation for mothers, see, for example: "Why Is Mommy So Stressed? Estimating the Immediate Impact of the COVID-19 Shock on Parental Attachment to the Labor Market and the Double Bind of Mothers," Heggeness, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Institute Working Paper 33, October 2020 (https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/institute-working-papers/why-is-mommy-so-stressed-estimating-the-immediate-impact-of-the-covid-19-shock-on-parental-attachment-to-the-labor-market-and-the-double-bind-of-mothers); "Pandemic Disproportionately Affects Women, Minority Labor Force Participation," Atkinson and Richter, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas , November 10, 2020 (https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2020/1110); "Parental Participation in a Pandemic Labor Market," Lofton, Petrosky-Nadeau, and Seitelman, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter 2021-10) (https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2021/april/parental-participation-in-pandemic-labor-market/); "Ten Economic Facts About How Mothers Spend Their Time," Bauer, Buckner, Estep, Moss, and Welch, The Hamilton Project, March 2021 (https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Maternal_Time_Use_Facts_final-1.pdf); "COVID-19 and the Labor Market Outcomes for Prime-Age Women," Luengo-Prado, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Current Policy Perspectives, April 2021. Return to text

6. For other analyses describing the steeper decline in labor force participation for minorities and less-educated mothers, see "Women without a College Degree, Especially Minority Mothers, Face a Steeper Road to Recovery," Didem Tuzeman, forthcoming, Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (https://www.kansascityfed.org/documents/8243/er21v106n3tuzemen.pdf); "Women's Labor Force Exits during COVID-19: Differences by Motherhood, Race, and Ethnicity," Lim and Zabek, Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Discussion Series, forthcoming. Return to text

7. For men and women without their own children in the household, about half of the increase in caregiving concerns is concentrated among adults who have household members who are age 65 and older, disabled adults, or children (but not the respondent's own children). This could reflect nonparticipants who are assisting with elder care, health care for other adults in the household, or caregiving for other children who aren't their own. Return to text

8. For other analysis on the burden of caregiving on labor force participation of mothers of very young children (ages 5 and younger) during the pandemic, see: "Pandemic pushes mothers of young children out of the labor force," Boesch, Grunewald, Nunn, and Palmer, Federal Reserve Bank of San Minneapolis, February 2021 (https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2021/pandemic-pushes-mothers-of-young-children-out-of-the-labor-force); "Where Are They Now? Workers with Young Children during COVID-19," Pitts, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, September 2021 (https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/research/publications/policy-hub/2021/09/01/10--where-are-they-now--workers-with-young-children-during-covid-19.pdf). Return to text

9. The reason we do not compare every month to February 2020 is that parents' nonparticipation for caregiving reasons generally exhibits significant seasonality during the summer months, rising as school summer vacations begin and falling as school restarts in the fall. We compare to the same pre-COVID calendar month, rather than seasonally adjusting the data, because in some of our analysis we examine smaller sub-groups where smaller sample sizes and more volatile monthly estimates preclude reliable seasonal adjustment. Return to text

10. Caregiving concerns also appear to have affected employed parents' ability to work their desired hours, although by a much smaller amount than appear to have experienced disruptions to labor force participation. As one way of examining this question, the CPS asks respondents who were employed but absent from their job, or usually full-time workers who were part-time during the reference week, whether the reason for the employment disruption was related to childcare. The fraction of mothers 25 to 54 with school-age kids reporting these types of disruptions has been elevated on average 0.1 to 0.2 percentage point throughout the pandemic—much smaller than the 1 to 3 percentage points that nonparticipation for caregiving reasons has been elevated. Return to text

11. This may be different from the fraction of students engaged in each type of education at any point, since some districts offer students a choice (e.g. either in-person or remote, or in-person, or hybrid) Return to text

12. The other variables included in the regression are: age indicator variables, education indicators, marital status indicators, and race and ethnicity indicators—all interacted with a COVID-era indicator (March 2020 and later); state of residence indicators; year and calendar-month indicators; and calendar-month indicators interacted with an indicator for whether the woman has a school age child. Women with younger children (age 5 and younger) are also included in the regression, and an indicator for whether women have only younger children is interacted with COVID month indicators as well as calendar month indicators. Return to text

13. Specifically, we are plotting the coefficient on each monthly indicator variable that is interacted with the indicator for being a mother with a school-age child. Because calendar-month indicator variables are included in the regression, these coefficients can be interpreted as the difference between mothers and non-mothers relative to the difference in the same calendar month for earlier years; thus the blue and red lines are directly comparable. Return to text

14. The regression results in Figures 4A and 4B use data from 2018 and later. We have estimated similar regressions using data from 2013 and later, and 2015 and later, and the results are broadly consistent with what we show here. We have also run similar regressions using matched CPS data—matching CPS respondents with their responses one year earlier—and additionally controlled for respondents' pre-COVID labor market status, and industry and occupation. These results are also broadly consistent with the results presented here. Return to text

15. For example, MCH Strategic Data estimates that as of late August, at least 85 percent of responding school districts indicated that they were offering in-person education for the start of the school year—see https://www.mchdata.com/covid19/schoolclosings/ . In addition, a July 2021 survey indicated that 89 percent of parents planned to send their children to school in-person for the start of the 2021-2022 school year (https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1393-2.html). Return to text

16. For example, reports compiled by Burbio's K-12 School Opening Tracker (https://cai.burbio.com/school-opening-tracker/) suggest that through mid-September, more than 1700 schools have had to move to virtual education, at least temporarily, due to reported COVID-19 cases in their classrooms. Return to text

Montes, Joshua, Christopher Smith, and Isabel Leigh (2021). "Caregiving for children and parental labor force participation during the pandemic," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, November 05, 2021, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3013.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.