FEDS Notes

January 08, 2020

Raising the Inflation Target: Lessons from Japan

1. Introduction

Equilibrium real interest rates across the world, including in the United States, have declined over the past few decades and are expected to stay at low levels going forward.2 All else equal, lower equilibrium real interest rates imply that the policy rate will be constrained by the effective lower bound (ELB) more frequently. In response to this development, some have argued that central banks should increase their inflation targets to create more policy space to address future recessions.3

Since the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) formally adopted an inflation targeting framework in 1990, many central banks have set an explicit inflation target as a way to help promote low and stable inflation. Overall, the experiences of these central banks suggest that adopting an explicit inflation target is useful in achieving low and stable inflation, especially when combined with specific actions aimed towards this goal.4 However, the success of adopting an explicit inflation target to lower inflation in the past may not necessarily imply the success of doing so to raise inflation in the future.

One central bank that has the experience of increasing its inflation target is the Bank of Japan (BOJ). In January 2013, the BOJ increased its inflation target from 1 percent to 2 percent in an effort to end the chronic deflation that had lasted for more than a decade.

In this note, I review this Japanese experience and highlight possible lessons for other central banks that may be interested in examining the possibility of raising their inflation target at some point in the future.

2. Japanese experience

Evolution of implicit and explicit inflation targets in Japan

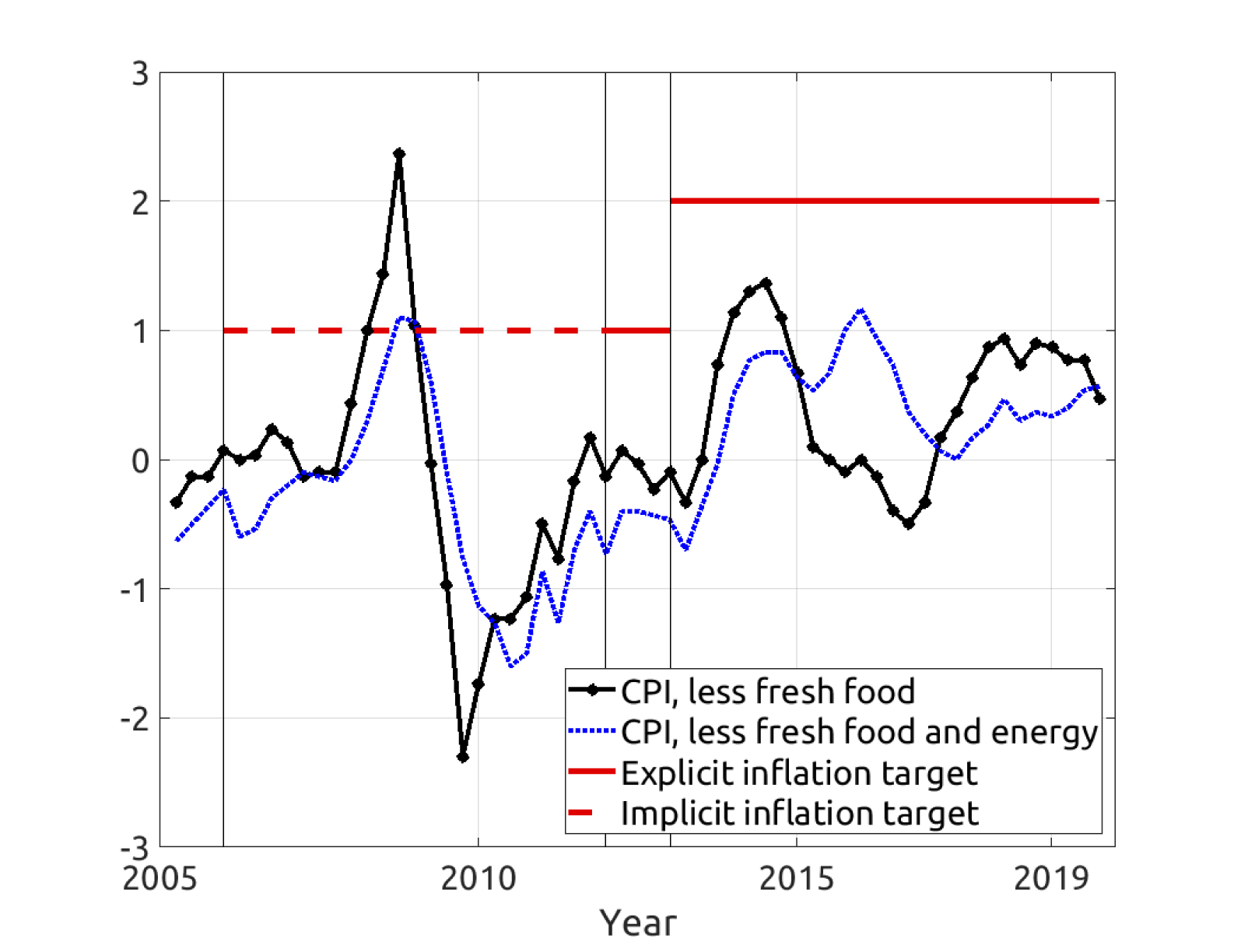

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the BOJ's implicit and then explicit inflation target—shown by dashed and solid horizontal red lines, respectively—as well as the evolution of actual inflation.

Note: The first vertical line is when the BOJ began reporting the views of Policy Board members regarding the rate of inflation consistent with medium- and long-term price stability (March 2006). The second vertical line is when the BOJ introduced a 1 percent inflation target (February 2012). The third vertical line is when the BOJ increased its inflation target from 1 percent to 2 percent (January 2013).

Source: The inflation series are quarterly and computed as the year-on-year percent change in CPI, less fresh food—shown by the solid black line with black circles—and the year-on-year percent change in CPI, less fresh food and energy—shown by the dotted blue line—both adjusted for the effects of the consumption tax hike in April 2014. Both series are available at the BOJ website.

The BOJ first adopted an explicit inflation objective of 1 percent in February 2012.5 Previously, the BOJ had reported information on the range and midpoint of the inflation rates Policy Board members viewed as consistent with price stability.6 The BOJ began collecting and reporting this information in March 2006 and annually surveyed the views of Policy Board members until 2011.7 During the six years from 2006 to 2011, the range of inflation rates deemed consistent with price stability by each policymaker was within the 0 to 2 percent interval, and the midpoint of the range was always 1 percent. Thus, it is sensible to see 1 percent as the BOJ's implicit inflation objective during this period.

In February 2012, as part of its efforts to demonstrate its determination to overcome deflation and to stimulate the economy, the BOJ announced its official inflation target, which was "within a positive range of 2 percent or lower" and was "1 percent for the time being."8 The introduction of an explicit inflation target was meant to be—and was perceived by market participants as—a significant departure from the previous practice of reporting the range/midpoint of views held by Policy Board members.9

About one year later—in January 2013—the BOJ raised its inflation target from 1 percent to 2 percent.10 The BOJ's inflation target has remained at 2 percent since then.

Evolution of inflation and real activity in Japan

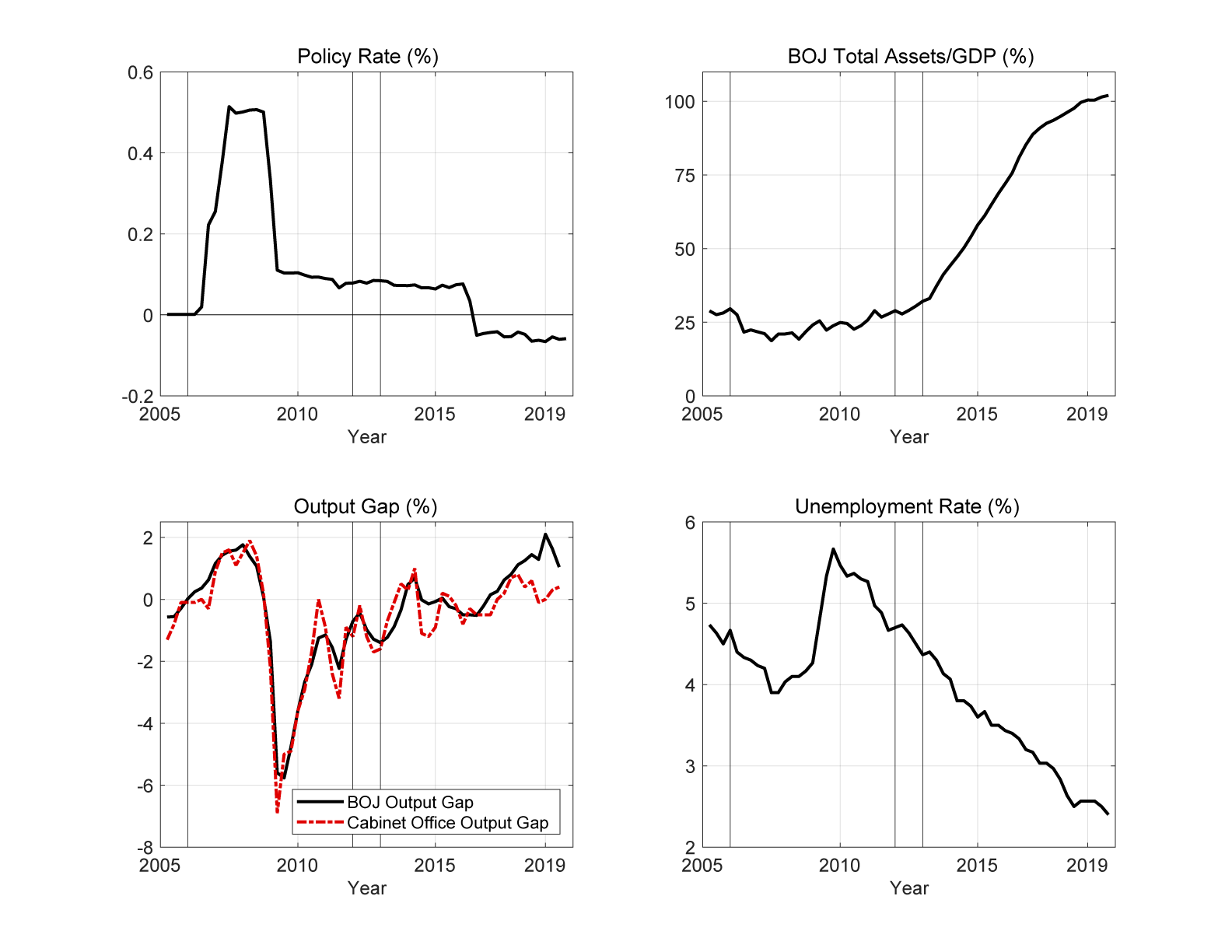

Since March 2013—when the BOJ introduced quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (often referred to as QQE)—it has taken various steps to stimulate the Japanese economy and increase the rate of inflation. Those measures include, among others, a rapid and substantial expansion of the central bank's balance sheet, more aggressive use of forward guidance, negative interest rate policy, and purchases of private securities through exchange-traded funds (ETFs).11 Most notable is the expansion of the BOJ's balance sheet. The size of the BOJ's balance sheet relative to GDP increased from around 30 percent in the first quarter of 2013 to over 100 percent in the third quarter of 2019, as shown in the top-right panel of Figure 2. Currently, the size of the balance sheet of the BOJ relative to the GDP in Japan is by far the largest of all central bank balance sheets.

Figure 2: Policy rate, balance sheet as a percentage of GDP, output gap, and unemployment rate in Japan

Note: The first vertical line is when the BOJ began reporting the views of Policy Board members regarding the rate of inflation consistent with medium- and long-term price stability (March 2006). The second vertical line is when the BOJ introduced 1 percent inflation target (February 2012). The third vertical line is when the BOJ increased its inflation target from 1 percent to 2 percent (January 2013).

Source: The BOJ policy rate series is the quarterly average of the "Call rate, Uncollateralized Overnight/Average" and is available at the BOJ website. The total assets series is from the BOJ's "Economic Statistics Monthly" publication. The nominal GDP series is from FRED-Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The BOJ output gap measure—shown by the solid black line—is available at the BOJ website, and that of the Cabinet Office—shown by the dash-dotted red line—is available at their website. The unemployment rate is from FRED-Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Since 2013, the output gap has picked up, and the unemployment rate has steadily declined, as shown in the bottom two panels of Figure 2. Inflation has also picked up, averaging about 0.5 percent since 2013, whereas inflation had hovered around a level below 0 percent for more than a decade prior to 2013. However, inflation still remains below the new target level of 2 percent. It is even below the old target level of 1 percent.12

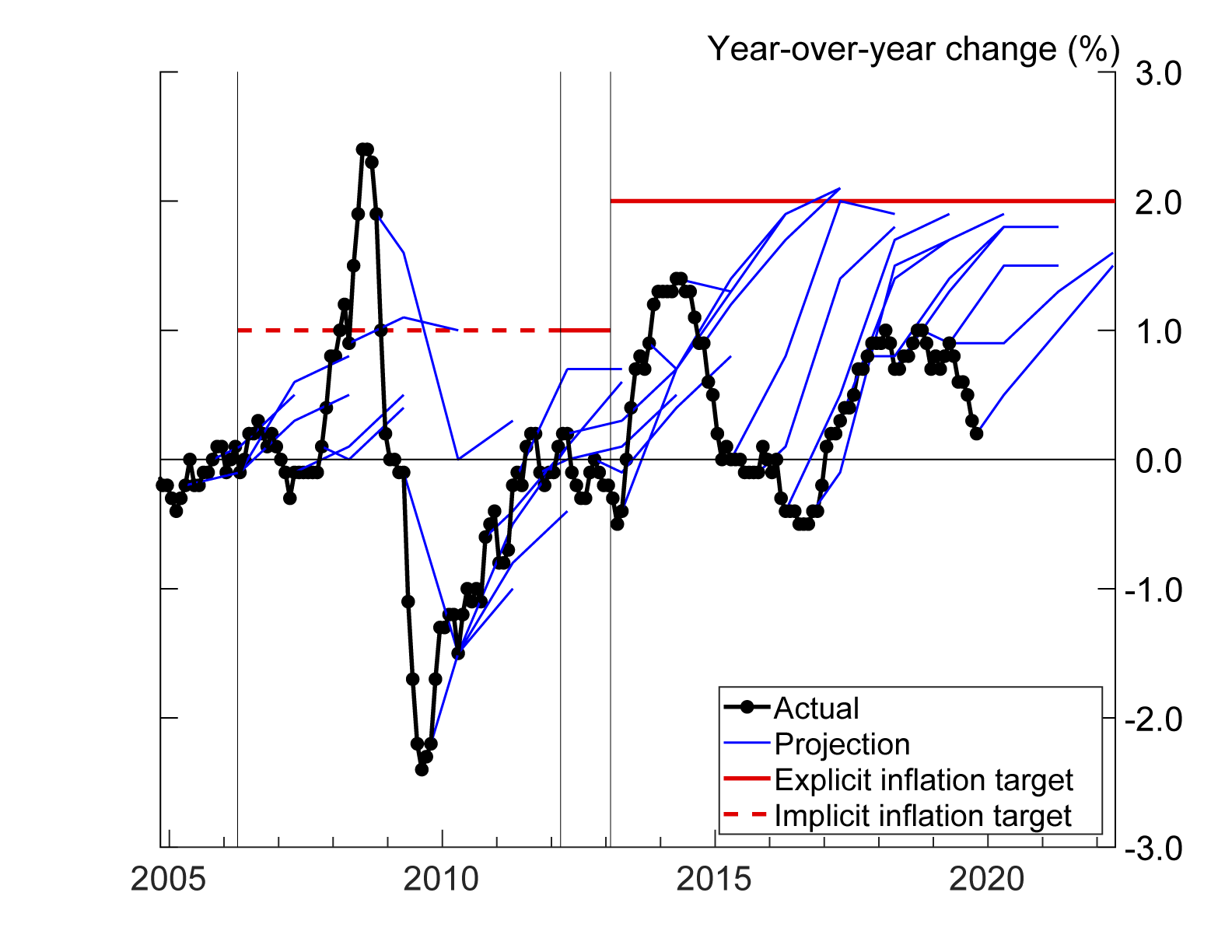

Note: The first vertical line is when the BOJ began reporting the views of Policy Board members regarding the rate of inflation consistent with medium- and long-term price stability (March 2006). The second vertical line is when the BOJ introduced a 1 percent inflation target (February 2012). The third vertical line is when the BOJ increased its inflation target from 1 percent to 2 percent (January 2013).

Source: The inflation series is monthly and computed as the year-on-year percent change in CPI, less fresh food—shown by the solid black line with black circles. It is adjusted for the effects of the consumption tax hike in April 2014 and is available at the BOJ website. The inflation projections—shown by the thin solid blue lines—are also for CPI, less fresh food, and adjusted for the consumption tax hikes in April 2014 and October 2019 as well as "policies concerning the provision of free education". These projections are from the "Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices" by the BOJ.

The difficulty of raising inflation to the new target level has surprised the BOJ and seasoned observers of the Japanese economy. Thin blue lines in Figure 3 show the BOJ's inflation forecasts at various points in time. Soon after the introduction of QQE in March 2013, the BOJ appreciably raised the projected path of inflation, forecasting that inflation would reach the new target of 2 percent in two years. As the actual inflation rate came in below the projections, the BOJ adjusted its forecasts downward. According to the most recent projection, the BOJ expects that inflation will not reach the 2 percent target until at least the end of FY2021—9 years after the adoption of the 2 percent target.13

All in all, the BOJ policy initiatives since 2013 have been a success in terms of real activity but only a partial success in terms of inflation.14

3. Lessons for other central banks

Because the Japanese economy has been dealing with a set of challenges that is somewhat unique, we do not know to what extent other countries can learn from the Japanese experience. Nevertheless, as historical experiences of raising the inflation target are limited, it is useful for other central banks to contemplate whether there are any lessons they can learn from the Japanese experience.

I see three possible lessons for other central banks considering the possibility of increasing their inflation targets in the future.

First, the Japanese experience shows that an announcement of a higher inflation target does not guarantee that inflation will increase to the new target level, even if the announcement is accompanied by a historically unprecedented degree of monetary accommodation. One could argue that the BOJ could have provided more accommodative monetary policy by even more aggressive asset purchase programs, interest rates at more negative levels, and better communication strategies.15 However, although such additional actions might have helped raise inflation to the new target level, it is highly uncertain whether these additional actions would have led to substantially higher inflation in Japan. In particular, there is a high degree of uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of asset purchase programs, especially when the size of the central bank's balance sheet is already large, as well as regarding the effectiveness of negative interest rate policy.16

The difficulty of raising inflation reflects a fundamental asymmetry in monetary policy arising from the ELB constraint. When central banks want to lower inflation, they can raise the policy rate without facing an upper bound. However, when they want to raise inflation, they may face the ELB constraint. No matter how aggressively they use other policy instruments at the ELB, central banks may not be able to fully unwind the effects of the ELB constraint.17

Thus, in thinking about whether to raise the inflation target to a certain level, central banks need to take into account whether they are able to raise inflation to the new target level. If a new inflation target is too ambitious, and the central bank fails to attain it, the central bank may lose its credibility, which may render less effective any other policies it pursues. Also, the central bank may face the risk of getting trapped in a never-ending monetary accommodation even when real economic activity is strong or when financial stability risks accumulate.

Second, for the central bank to convince the public that it is capable of raising inflation to a new, higher target, it is likely useful for the central bank to have achieved the old, lower target in a sustainable manner before adopting a higher target. As shown in Figure 1, the BOJ raised the inflation target from 1 percent to 2 percent when inflation had been consistently below 1 percent for more than a decade. It is likely difficult for the public to believe in the central bank's ability to raise inflation to a new higher target if the central bank has not been able to achieve the old, lower target in the past.18 In the context of other advanced economies, this lesson means that, if central banks were to raise their inflation target at some point in the future, they would be more likely to succeed if they announce the new inflation target after having consistently achieved the symmetric 2 percent inflation objective (for the case of the Federal Reserve) or the inflation objective of being below, but close to, 2 percent (for the case of the ECB).

Third, it is likely helpful to build a consensus among policymakers and the public on the desirability of a higher inflation target. In the case of Japan, two out of nine BOJ Policy Board members voted against the introduction of the 2 percent inflation target in January 2013. When there is disagreement about the desirability of the new inflation target among policymakers, it is hard for the public to believe that future policymakers will be able to stick to the new inflation target. This consideration might have been particularly important for the BOJ because, as discussed earlier, the BOJ departed from the previous 1 percent inflation target just one year after it formally adopted it.

4. Putting the Japanese experience in perspective

After the adoption of an inflation target regime, central banks have typically either kept the inflation target unchanged or reduced it. As an example of the former, the Bank of Canada's inflation target range has been 1 to 3 percent since 1993, when the range was introduced for the first time.19 As an example of the latter, the Czech National Bank (CNB) has lowered its inflation target range in several steps since it adopted the inflation targeting framework in 1998. The inflation target range of the CNB was 5.5 to 6.5 percent in 1998. The target range has been 1 to 3 percent since 2010.20

While the policy of raising the inflation target is less common, it is not unprecedented. For example, the RBNZ modified its inflation target range from 0 to 2 percent to a range of 0 to 3 percent in 1996, pushing up the midpoint from 1 percent to 1.5 percent. The RBNZ modified the range again in 2003 from 0-to-3 percent to 1-to-3 percent, pushing up the midpoint from 1.5 percent to 2 percent.21 Another, and perhaps subtler, precedent comes from the ECB. In 2003, the ECB modified the definition of the inflation target from "below 2 percent" to "below, but close to, 2 percent."22

Relative to the experiences of these two central banks, the BOJ's experience is unique in that it was more recent, it was undertaken when the policy rate was constrained at the ELB, and the size of the increase in the inflation target was large (one percentage point).

5. Conclusions

In this note, I reviewed the BOJ's experience of raising its inflation target in January 2013 and discussed a few possible lessons for other central banks that may be interested in examining the possibility of raising their inflation target in the current environment of low equilibrium rates.

I have abstracted from the issue of whether it is optimal for central banks to increase the inflation target from a welfare perspective. The logic that a higher ELB frequency should raise the optimal inflation target is certainly correct, yet there is disagreement and uncertainty regarding how much ELB frequency has increased and how much such an increase in ELB frequency increases the optimal inflation target.23 Also, even though the current inflation targets were perhaps optimal up to the first order when they were instituted—given that the main concern of central banks was to avoid the return of high and volatile inflation of the type seen in the 1970s and 1980s—they might not have been fine-tuned to be "the" optimal level in an era of low and stable inflation. For example, the optimal inflation target might have been around 1.5 percent in the past and might be close to 2 percent now after taking into account a higher ELB frequency.24 I leave quantitative investigations of the optimal inflation target to future research.

References

Apel, Mikael, Hanna Armelius and Carl Andreas Claussen (2017): "The Level of the Inflation Target—A Review of the Issues," Sveriges Riksbank Economic Review. 2017(2). pp. 36-56.

Ball, Laurence (2013): "The Case for Four Percent Inflation," Central Bank Review, 13(2). pp. 17–31.

Bank of Canada (1991): "Targets for Reducing Inflation," February 26, 1991.

Bank of Canada (1993): "Statement of the Government of Canada and the Bank of Canada on Monetary Policy Objectives," December 22, 1993.

Bank of Canada (2019): "Agreement on the Inflation-Control Target" https://www.bankofcanada.ca/agreement-inflation-control-target/

Bank of Japan (2006): "The Introduction of a New Framework for the Conduct of Monetary Policy," March 9, 2006.

Bank of Japan (2012): "The Price Stability Goal in the Medium to Long Term," February 14, 2012.

Bank of Japan (2013a): "The "Price Stability Target" under the Framework for the Conduct of Monetary Policy," January 22, 2013.

Bank of Japan (2013b): "Introduction of the "Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing"" April 4, 2013.

Bank of Japan (2016a): "Introduction of "Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with a Negative Interest Rate"" January 29, 2016.

Bank of Japan (2016b): "Comprehensive Assessment: Developments in Economic Activity and Prices as well as Policy Effects since the Introduction of Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE)," September 21, 2016.

Bank of Japan (2018): "Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices (July 2018)—Analysis on Wages and Prices," July 31, 2018.

Bernanke, Ben S., Thomas Laubach, Frederic S. Mishkin, and Adam S. Posen (1999): "Inflation Targeting: Lessons from the International Experience." Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Blanchard, Olivier, Giovanni Dell'Ariccia, and Paolo Mauro (2010): "Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy," Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol. 42 (Supplement), pp. 199–215.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Adam Posen (2015): "Japan's Solution Is to Raise Wages by 10 Percent," Financial Times, December 2, 2015.

Coyle, Philip, and Taisuke Nakata (2019): "Optimal Inflation Target with Expectations-Driven Liquidity Traps," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-036. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Central Bank of Brazil (2019): "Inflation Targeting Track Record," https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/monetarypolicy/historicalpath

Central Bank of Chile (2007): "Central Bank of Chile: Monetary Policy in an Inflation Targeting Framework."

Czech National Bank (2019): "Inflation Targeting in the Czech Republic," https://www.cnb.cz/en/monetary-policy/inflation-targeting/

De Michelis, Andrea, and Matteo Iacoviello (2016): "Raising an Inflation Target: The Japanese Experience with Abenomics," European Economic Review, vol. 88, pp. 67-87.

Debortoli, Davide, Jordi Galí, and Luca Gambetti (2019): "On the Empirical (Ir)relevance of the Zero Lower Bound Constraint," National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper No. 25820. www.nber.org/papers/w25820.pdf.

Diercks, Anthony (2019): "The Reader's Guide to Optimal Monetary Policy," Mimeo. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2989237

Eggertsson, Gauti, Ragnar Juelsrud, Lawrence Summers, and Ella Getz Wold (2019): "Negative Nominal Interest Rates and the Bank Lending Channel," NBER Working Paper No. 25416.

European Central Bank (2019): "The Definition of Price Stability," https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/strategy/pricestab/html/index.en.html

Gagnon, Etienne, Benjamin K. Johannsen, and David López-Salido (2016). "Understanding the New Normal: The Role of Demographics," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016-080. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Greenlaw, David, James Hamilton, Ethan Harris, Kenneth West (2018): "A Skeptical View of the Impact of the Fed's Balance Sheet," NBER Working Paper No. 24687.

Hausman, Joshua K, and Johannes Wieland (2015): "Overcoming the Lost Decades? Abenomics after Three Years," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Vol. 46(2), pp. 385-413.

Holston, Kathryn, Thomas Laubach, and John C. Williams (2017): "Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants," Journal of International Economics, vol. 108, Supplement 1, pp. S59-S75.

Kiley, Michael (2019): "The Global Equilibrium Real Interest Rate: Concepts, Estimates, and Challenges," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-076. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Kiley, Michael, Eileen Mauskopf, and David Wilcox (2007): "Issues Pertaining to the Specification of a Numerical Price-Related Objective for Monetary Policy," Memo, March 12. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

McDermott, John, and Rebecca Williams (2018): "Inflation Targeting in New Zealand: An Experience in Evolution," A speech delivered to the Reserve Bank of Australia conference on central bank frameworks, Sydney, Australia. December 4th, 2018

Magyar Nemzeti Bank (2019): "Inflation Targeting," https://www.mnb.hu/en/monetary-policy/monetary-policy-framework/inflation-targeting

Mineyama, Tomohide, Wataru Hirata and Kenji Nishizaki (2019): "Inflation and Social Welfare in a New Keynesian Model: The Case of Japan and the U.S." Bank of Japan Working Paper Series 19-E-10, Bank of Japan.

Momma, Kazuo, and Shunji Kobayakawa (2014): "Monetary Policy after the Great Recession: Japan's Experience," in Monetary Policy after the Great Recession. Edited by Javier Vallés. FUNCAS Social and Economic Studies. Madrid, Spain.

Nishizaki, Kenji, Toshitaka Sekine and Yoichi Ueno (2014): "Chronic Deflation in Japan," Asian Economic Policy Review, Vol. 9(1), pp. 20-39.

Norges Bank (2013): "New Regulation on Monetary Policy," https://www.norges-bank.no/en/news-events/news-publications/Press-releases/2018/2018-03-02-press-release/

Posen, Adam (2014): "Kuroda's Plan is Working," Nikkei Asian Review, May 29, 2014.

Posen, Adam (2015): "Comments on "Overcoming the Lost Decades? Abenomics after Three Years,"" Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Vol. 46(2), pp. 414-426.

Reifschneider, David (2016). "Gauging the Ability of the FOMC to Respond to Future Recessions," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016–068. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Roberts, John M. (2018): "An Estimate of the Long-Term Neutral Rate of Interest," FEDS Notes 2018-09-05. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Shapiro, Adam Hale and Daniel Wilson (2019): "Taking the Fed at Its Word: A New Approach to Estimating Central Bank Objectives using Text Analysis," Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2019-02.

Sveriges Riksbank (2019): "The Inflation Target," https://www.riksbank.se/en-gb/monetary-policy/the-inflation-target/

Watanabe, Kota, and Tsutomu Watanabe (2018): "Why Has Japan Failed to Escape from Deflation?" Asian Economic Policy Review, Vol. 13(1), pp. 23-41.

1. I thank Mark Wilkinson for editorial and research assistance, and Andrea De Michelis, Anthony Diercks, Eric Engen, Yasuo Hirose, Mike Kiley, Andrew Levin, David López-Salido, Mathias Paustian, John Roberts, Takeki Sunakawa, Hiroatsu Tanaka, and Robert Tetlow for valuable comments. The views expressed in this article, and all errors and omissions, should be regarded as those solely of the author, and are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. See, for example, Gagnon et al. (2016), Holston et al. (2016), Kiley (2019), and Roberts (2018). Return to text

3. See, for example, Blanchard et al. (2010) and Ball (2013). Return to text

4. See, for example, Bernanke et al. (2001). Return to text

5. See Bank of Japan (2012). Return to text

6. See Bank of Japan (2006). Return to text

7. The BOJ referred to this range and midpoint of inflation rates consistent with price stability as the "understanding of medium- and long-term price stability." Return to text

8. See Nishizaki et al. (2014) for a comprehensive survey of possible causes of chronic deflation in Japan. Return to text

9. To be precise, the BOJ used the term "goal" in the framework introduced in February 2012, while it used the term "target" in the framework introduced in January 2013. See Momma and Kobayakawa (2014) for how differently the BOJ interpreted these two terms. Return to text

10. See Bank of Japan (2013a). Return to text

11. See Bank of Japan (2013b) and Bank of Japan (2016a). Return to text

12. Measures of long-run inflation expectations picked up in 2013 and 2014, but came down in 2015 and 2016 as the economy weakened in the aftermath of the April 2014 consumption tax hike (see De Michelis and Iacoviello (2016)). Since 2017, many measures of long-run inflation expectations have been only slightly higher than, or about the same as, the level that prevailed before 2013 (see, for example, the latest "Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices" by the BOJ). Return to text

13. See Bank of Japan (2016b) and Bank of Japan (2018) for possible explanations for why it has been difficult for the BOJ to achieve the new inflation target. See also De Michelis and Iacoviello (2016) for a model-based analysis of inflation dynamics in Japan after the adoption of the 2 percent target. Return to text

14. See Hausman and Wieland (2015) and Posen (2015) for assessments of the performance of the Japanese economy in late 2015. Return to text

15. There are other policies that the BOJ could have pursued (and could pursue now) which would require cooperation of other governmental agencies, such as an exchange-rate peg to keep the yen even more depreciated (Hausman and Wieland (2016)) or promoting higher wages in sectors for which the government can exert influences (Blanchard and Posen (2015)). While the list of "what else the BOJ could have done" is long, it is useful to remind ourselves that many seasoned experts of the Japanese economy welcomed the BOJ's QQE (see, for example, Posen (2014)) and that there were not many voices urging the BOJ to do more in 2013. Return to text

16. In particular, see Greenlaw et al. (2018) and Eggertsson et al. (2019) for skeptical views regarding the effectiveness of asset purchase programs and negative interest rate policy. Return to text

17. In the U.S. context, Reifschneider (2016) has argued that modest amounts of asset purchases coupled with a threshold-type forward guidance policy could provide about as much stimulus as would a benchmark policy rule if unconstrained by the ELB. Results in Debortoli et al. (2019s) suggest that such alternative monetary policies may have provided about the same amount of stimulus in reaction to adverse shocks during the ELB period as in the prior period. Return to text

18. Also, many years of inflation below the old low target likely mean that long-run inflation expectations relevant for price and wage setting are firmly anchored at a level below the old target (see Watanabe and Watanabe (2018)). When long-run inflation expectations are firmly anchored at a low level, the process of the transition of actual inflation to the new, high target level is likely very prolonged, even if the public believes in the central bank's ability to eventually achieve the new target. Return to text

19. See Bank of Canada (2019). The Bank of Canada (BOC) introduced the inflation target framework in March 1991 (Bank of Canada (1991)). At the time, the BOC specified the inflation target path for the near and medium term, aiming to achieve 2 percent by the end of 1995. The BOC refrained from setting specific targets after 1995, stating that the target path after 1995 would be specified once "further evidence and analysis" regarding what price stability operationally means became available. It is interesting to note that, while the BOC refrained from setting targets beyond 1995, it also stated that a rate of increase in consumer prices consistent with price stability is "clearly below 2 percent." The BOC in 1993 disagreed with this numerical assessment (Bank of Canada (1993)). The Riksbank has also kept their inflation target unchanged—at 2 percent—since adopting the inflation targeting framework (see Sveriges Riksbank (2019)). Return to text

20. Other central banks in this category include—but are not limited to—the Central Bank of Chile and the Norges Bank (see Central Bank of Chile (2019) and Norges Bank (2018)). Return to text

21. See McDermott and Williams (2018) and Apel et al. (2017). Inflation in New Zealand has fluctuated within the target range of 1 to 3 percent most of the time since the range was adopted in 2002. Return to text

22. See European Central Bank (2019). Other central banks with the experience of raising the inflation target include—but are not limited to—the Magyar Nemzeti Bank and the Central Bank of Brazil. These two central banks frequently adjusted their inflation target in the 2000s. See Magyar Nemzeti Bank (2019) and Central Bank of Brazil (2019). Return to text

23. Various factors affect the optimal inflation target of an economy—see, for example, Kiley et al. (2007)—and the range of estimates of the optimal inflation target in the academic literature is wide, as shown by Diercks (2019). Also, in each study, the optimal inflation target is sensitive to parameter values (see, for example, Coyle and Nakata (2019), Coibion et al. (2012), and Mineyama et al. (2019)). Return to text

24. According to Shapiro and Wilson (2019), until 2009, most FOMC participants who expressed their views on a specific numerical value for the potential inflation target voiced their preference for a target below 2 percent (typically 1 percent or 1.5 percent). In the March 2007 FOMC meeting, four members expressed a preference for 1.5 percent, three for between 1.5 and 2 percent, two for 1 percent, and one for 2 percent, illustrating the inherent uncertainty in the optimal inflation target. Return to text

Nakata, Taisuke (2019). "Raising the Inflation Target: Lessons from Japan," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 8, 2020, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2493.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.