FEDS Notes

September 19, 2025

Rising Property Insurance Costs and Pass-Through to Rents for Apartment Buildings1

Samuel K. Hughes and Raven Molloy

Introduction

Substantial increases in homeowners' insurance costs since the late 2010s have raised homeowners' housing costs.2 Spreading reports about similar insurance cost increases for apartment buildings may prompt similar questions about the implications for renters' costs.3 In this analysis, we show that property insurance costs have increased substantially for multifamily buildings, and we examine the implications for rental markets. Specifically, we assess the extent to which these cost increases are passed on to tenants by examining how landlords' rental revenues, asking rents, other costs shifted in conjunction with these cost increases.

It would be natural to expect landlords to protect their profits by passing insurance cost increases along to their tenants. However, if tenants are sensitive to rent increases and if other properties in the same market are not raising rents, then landlords may lose tenants if they raise their rent in response to insurance cost increases. Therefore, the degree of pass-through is an empirical question. We expect the answer to depend on heterogeneity in these cost increases within rental markets, the current state of local rental markets, and the price elasticity of rental demand.

We find that, like homeowners' insurance, multifamily property insurance costs increased considerably from 2019 to 2024. The average monthly cost increased from $39 per unit in 2019 to $68 per unit in 2024 in real terms, an increase of more than 75 percent. Similar to Kim, Mahajan and Wang (2025), we find that a building's rental revenues tend to rise at the same time as its property insurance costs, suggesting that landlords may increase rent to partly offset these higher costs. By contrast, we find that there is little relationship between average changes in insurance costs and changes in asking rents. This lack of correlation suggests that the increase in revenue may stem from changes in the rents of existing tenants, which could be the case if existing tenants are less sensitive to price changes than new tenants. We find no evidence that landlords offset rising insurance costs by reducing other expenses. Putting the components of the operating statement together, we find that a dollar increase in property insurance costs reduces property owners' net income by about 72 cents. Therefore, this evidence suggests that rising property insurance costs tend to be borne more by property owners than by renters. Even so, our estimates suggest that rents paid by the average apartment tenant have risen by 7 to 12 dollars per month (less than one percent of average rent) due to the increase in property insurance costs since 2019.

Data Description

The main data for this analysis come from annual operating statements for individual multifamily properties that have mortgages securitized in CMBS pools. The operating statements are reported so that CMBS servicers and investors can assess changes in the financial health of the property, which could affect the likelihood of mortgage delinquency. The data are compiled by Trepp, LLC. We limit the sample to operating statements that are original borrower-reported, annualized statements covering a 12-month period and ending in December.4 The data cover the years 2000 to 2024, with the number of observations growing over time as the securitized multifamily segment expanded—from about 2 thousand in 2000 to 24-28 thousand per year over 2019-2024.5 Multifamily properties securitized by mortgages in CMBS pools tend to be larger, newer and higher quality than the overall multifamily stock. Hence, these properties tend to be in urban areas. Nevertheless, the geographic coverage of the data is quite broad. In the same-property sample covering 2019-2024, there are at least 10 properties per year in more than 150 metropolitan areas across the U.S. On average, there are about 172 units per property and the average property was built in 1977. Table 1 reports summary statistics of the sample.

Table 1: Summary Statistics

| Mean | SD | P10 | Median | P90 | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance Pct of Revenue | 3.23 | 2.61 | 1.13 | 2.58 | 5.99 | 341017 |

| Insurance Per Unit | 42.33 | 36.09 | 14.92 | 33.13 | 78.67 | 341017 |

| ∆ Log Insurance Per Unit | 0.06 | 0.42 | -0.26 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 235062 |

| Revenue Per Unit | 1465.43 | 896.45 | 749.05 | 1248.51 | 2348.42 | 341017 |

| ∆ Log Revenue Per Unit | 0.01 | 0.09 | -0.07 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 235064 |

| Expenses Ex-Insurance Per Unit | 641.81 | 545.86 | 325.48 | 527.19 | 952.84 | 341017 |

| ∆ Log Expenses Ex-Insurance Per Unit | 0.02 | 0.17 | -0.14 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 234895 |

| Maintenance & Repair Expenses Per Unit | 100.9 | 88.88 | 36.3 | 79.21 | 185.15 | 339760 |

| ∆ Log Maint & Repair Exp Per Unit | 0.01 | 0.38 | -0.4 | 0.01 | 0.43 | 233831 |

| Net Operating Income Per Unit | 781.28 | 597.64 | 272.68 | 649.08 | 1425.9 | 341017 |

| %∆ Net Operating Income Per Unit | 0 | 0.31 | -0.22 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 235065 |

| Net Rental Income Yield | 8.11 | 3.76 | 4.23 | 7.58 | 12.78 | 337035 |

| ∆ Net Rental Income Yield | 0.03 | 1.97 | -1.67 | 0.05 | 1.67 | 233739 |

| Year | 2016.31 | 6.09 | 2007 | 2018 | 2023 | 341017 |

| Mortgage Orig Year | 2012.89 | 6.68 | 2003 | 2015 | 2020 | 341017 |

| Property Built Year | 1977.17 | 28.12 | 1931 | 1981 | 2008 | 340133 |

| Number of Units | 171.84 | 202.57 | 18 | 128 | 356 | 341017 |

Note: Dollar values are adjusted for inflation using the CPI-U, in 2023 dollars. Observations are at the property-by-year level from 2000-2024. Annual values are converted to monthly, per unit values by dividing by the number of units in the property and then dividing by 12.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; Authors' analysis.

The operating statements include a range of line items for annual property revenues and costs. We transform these annual values to monthly, per unit values for ease of interpretation. Particularly useful for this analysis, one of the cost-related line items is for property insurance. This line item includes costs associated with flood insurance, hazard liability, general insurance, and other property insurance. The reporting forms do not include specific mentions of insurance for other hazards like fire and wind, but the cost for these types of insurance should be included in this measure.6

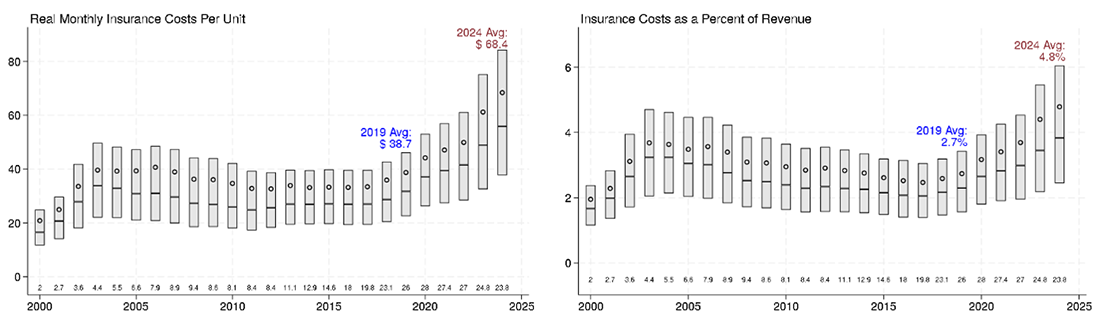

Figure 1 shows the distribution of property insurance costs per unit in each year of our sample, deflated by the CPI-U. This distribution was quite stable from 2003 to 2018, illustrating that property insurance costs were generally rising at the same rate as inflation. Thereafter, the distribution shifted up every year. By 2024, the average and median insurance costs were each about 75 percent higher than in 2019. We find similar rates of increases in a sample restricted to an identical set of properties in 2019 and 2024, illustrating that these increases in insurance costs are not due to changes in the types of properties in the sample. Figure 1 also shows that insurance costs have increased relative to property revenues, but they were still only 5 percent of revenues for the average property in our sample in 2024. The fact that insurance costs have grown relative to revenue indicates that landlords are bearing some of these cost increases.

Note: Left-hand graph on monthly insurance costs per unit contains mean (dot), 25th-to-75th percentile range (gray box), median (black line, middle of gray box), and thousands of properties (below 0 on x-axis). Real values adjusted by CPI-U, in 2023 dollars. Values are trimmed at the 0.5 and 99.5 percentile. Right-hand graph on annual insurance costs divided by annual revenue contains mean (dot), 25th-to-75th percentile range (gray box), median (black line, middle of gray box), and thousands of properties (below 0 on x-axis).

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

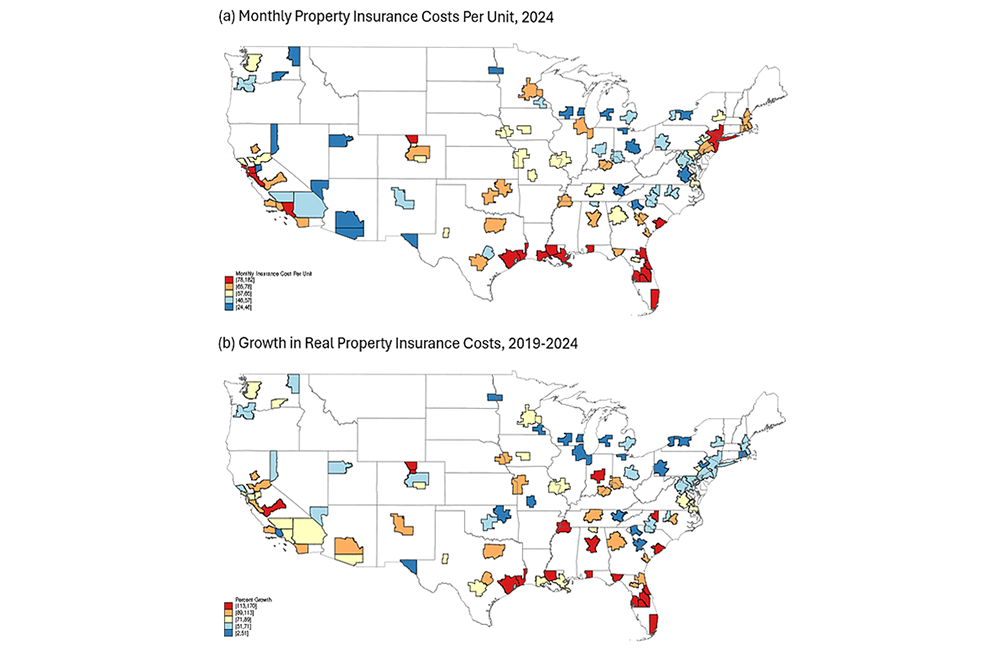

Figure 2 shows the geographic distributions of property insurance costs and recent increases. Specifically, panel (a) of the figure shows that in 2024, average property insurance costs per unit were much higher in Florida and the coasts of Louisiana and Texas than in most other parts of the US. Costs also tended to be relatively high in the area around New York City and in some parts of southern California. Panel (b) maps average increases by metropolitan area from 2019 to 2024 for metros where our sample has at least 10 properties. Increases have tended to be largest in Florida and the coasts of Louisiana and Texas. In addition, increases were larger in the Southeastern and central Midwestern parts of the country relative to the Northeast, upper Midwest, and the northern half of the West Coast. Overall, there is a substantial amount of heterogeneity in apartment insurance costs and recent increases in these costs across the US.

Note: Top map shows level of insurance costs per unit in 2024 by core-based statistical area (CBSA). Bottom map of percent growth in average within-property insurance costs from 2019-2024. Map only shows CBSAs with more than 10 observations of insurance cost growth for the same property from 2019 to 2024. Colors are split into 5 groups by quintile in the distribution of each variable.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; U.S. Census Bureau; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

To further describe the geographic heterogeneity in insurance cost increases, Table 2 shows the amount of variation in cost increases that can be explained by various categories of fixed effects. Column 1 indicates that only around 4 percent of the variation in insurance cost growth is explained by common nationwide variation by year (R-squared of 0.04). Static metropolitan area factors also matter little (Column 2). Column 3 shows that 12 percent of variation in insurance cost growth is explained by common metro area-by-year factors. The factor that seems the most important is ZIP code-by-year variation, explaining more than 42 percent of the variation in insurance cost growth (Column 6). If one considers a ZIP code to be a rough proxy for the neighborhood rental market, then these results suggest that a little less than half of the variation in property insurance cost increases is common to all properties in a market. Even within ZIP codes, some of the variation in insurance cost growth appears to be property-specific, as adding property fixed effects increases the R-squared by 12 percent (Column 7). The remaining columns of the table show that results are similar for 2019-2024, when insurance cost increases tended to be larger.

Table 2: Explaining Variation in Annual Insurance Cost Growth

| ∆ Log Real Insurance Costs Per Unit | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Constant | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.110*** | 0.110*** | 0.111*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| R-Squared | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.55 |

| Time Period | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2019-24 | 2019-24 | 2019-24 |

| Obs. | 186857 | 186857 | 186857 | 186857 | 186857 | 186857 | 186857 | 98137 | 98137 | 95413 |

| Number Zip Codes | 5377 | 5377 | 5377 | 5377 | 5377 | 5377 | 5377 | 4773 | 4773 | 4625 |

| Number Properties | 45747 | 45747 | 45747 | 45747 | 45747 | 45747 | 45747 | 30424 | 30424 | 27776 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| CBSA FE | Yes | |||||||||

| CBSA-Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Zip Code FE | Yes | |||||||||

| Zip-Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Property FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

Note: Each column controls for fixed effects, and reports R-squared for the specification. Columns 8-10 only include observations from 2019-2024. Constant term shows average annual growth in real insurance costs per unit, standard errors clustered by zip code. Real values adjusted by CPI-U, in 2023 dollars.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

Revenues, Asking Rents and Occupancy

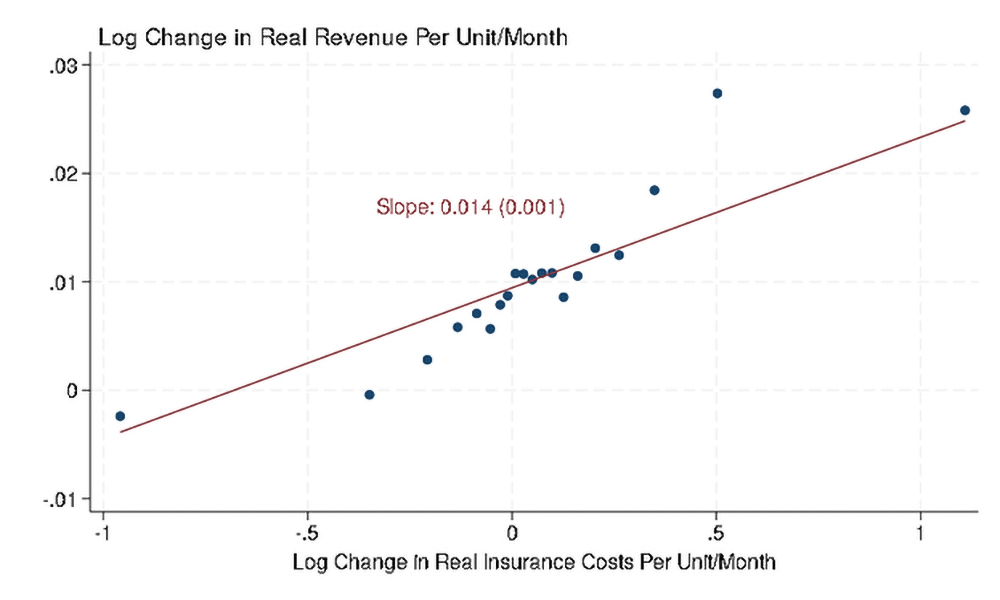

Figure 3 takes a first look at landlords' response to rising property insurance costs by showing the relationship between insurance cost growth and revenue growth in a binned scatter plot. There is a positive relationship with a 10 percent increase in real insurance costs associated with a 0.14 percent increase in revenues. This relationship looks fairly linear and is symmetric for cost increases and cost decreases. Table 3 shows that this relationship is robust to including a variety of fixed effects and controls for property age, property size, property renovations, and county economic conditions. This relationship is similar during the 2019-2024 period as in the full sample. And the relationship appears to be contemporaneous, as leads and lags of insurance cost changes are not related to revenues.

Note: Binned scatter plots contain 20 groups. Real values adjusted by CPI-U, in 2023 dollars.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

Table 3: Relationship Between Growth in Multifamily Insurance Costs and Revenues

| ∆ Log Real Monthly Revenue Per Unit | ∆ $ Revenue | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| F1.∆ Log Real Insurance Per Unit | 0.000 | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| ∆ Log Real Insurance Per Unit | 0.014*** | 0.014*** | 0.011*** | 0.008*** | 0.009*** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| L1.∆ Log Real Insurance Per Unit | -0.000 | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| ∆ Real Insurance Per Unit | 0.394*** | 0.247*** | |||||

| (0.030) | (0.037) | ||||||

| Time Period | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2019-24 | 2000-24 | 2019-24 |

| Avg Revenue Per Unit | 1460 | 1460.8 | 1506.4 | 1432.9 | 1570.4 | 1434.4 | 1543.6 |

| Avg Insurance Per Unit | 43.3 | 43.3 | 44.3 | 41.4 | 52.2 | 42.1 | 50.8 |

| Obs. | 232795 | 232144 | 184321 | 110825 | 111968 | 232277 | 112018 |

| R-Squared | 0 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Number Zip Codes | 7510 | 7480 | 5348 | 6517 | 6324 | 7480 | 6336 |

| Number Properties | 65112 | 64930 | 45255 | 36950 | 40428 | 64993 | 40531 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| CBSA FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Zip Code-Year FE | Yes | ||||||

| Property FE | Yes | ||||||

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. Clustering standard errors by zip code. Columns 5 and 7 only include observations from 2019-2024. Other controls include log property built year, log number of units, 7 leads and lags around year of any renovation, log of county employment, log county average weekly wages, annual growth in employment, and annual growth in wages. Real values adjusted by CPI-U, in 2023 dollars.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

An elasticity of about 0.01 may seem small, but this result is partly because property insurance costs are a small fraction of revenue (as shown in Figure 1). Columns 6 and 7 regress the dollar change in revenues on the dollar change in insurance costs. In this case, the coefficients range from 0.25 to 0.4, implying that a dollar increase in insurance costs is generally associated with an increase in revenues of about 25 to 40 cents. In that sense, landlords appear to be offsetting about one third of these cost increases by raising revenues. Assuming that the dollar change in revenues is equivalent to the dollar change in average rents, the increase in average insurance costs is related to a 7 to 12 dollar increase in monthly rents paid by the average tenant.7

Landlords have several ways to raise revenues: they can raise asking rents for new tenants, they can raise rents for existing tenants, and they can take actions to increase occupancy rates. The operating statements do not have information on these channels.8 Therefore, we merge the operating statements by property address with property-specific data on asking rents and occupancy rates from RealPage, which collects this information using a combination of data provided by property managers and their own survey of properties. About 17 percent of the annual multifamily operating statements can be matched successfully with the RealPage data. The correlation of changes in insurance costs with changes in revenues is the same in this sample as in the full sample (not shown).

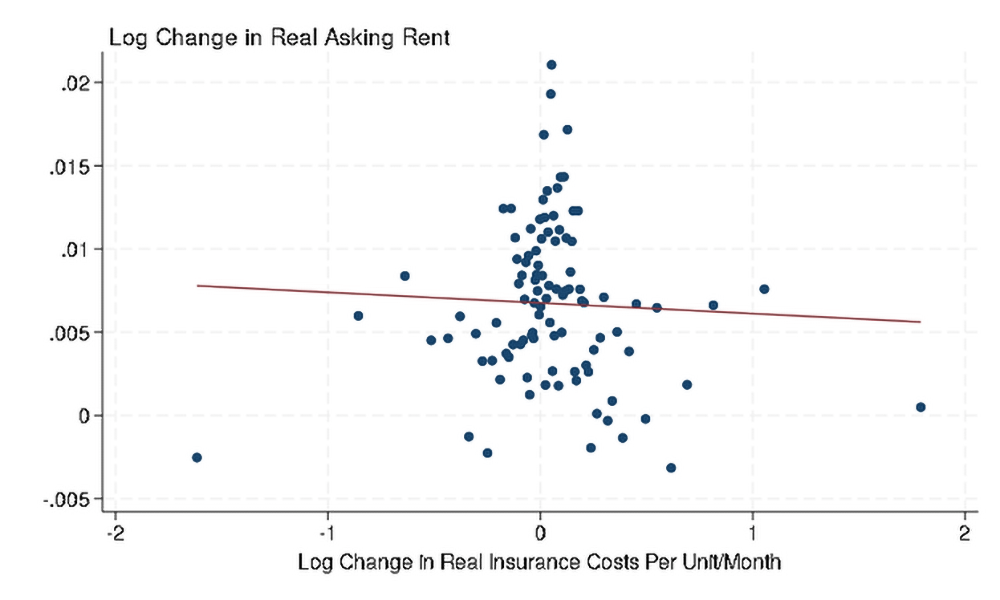

Figure 4 shows little correlation between insurance cost changes and changes in asking rent. Specifically, the figure shows a binned scatter plot (with 100 bins) where most of the properties with large changes in asking rent had little change in insurance costs. The changes in asking rent for properties with larger cost increases were no greater than those for properties with declines in insurance costs. Table 4 shows that we still find no relationship between these measures when including controls. We find precise null relationships between changes in insurance costs with changes in log asking rents, effective rents (where concessions and free rent deals are netted out), and dollar changes in asking rents.

Note: Binned scatter plots contain 100 groups. Real values adjusted by CPI-U, in 2023 dollars. Excludes values of change in log insurance of greater than 5 or less than -5 and change in log asking rent of greater than 1 or less than -1.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; RealPage, Inc., Rental Markets data; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

Table 4: Relationship Between Growth in Multifamily Insurance Costs and Asking Rents

| ∆ Log Real Asking Rent | ∆ EffRent | ∆ $AskRent | 1[∆ AskRent = 0] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| F1.∆ Log Real Insur Per Unit | -0.002 | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| ∆ Log Real Insur Per Unit | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.000 | 0.001 | -0.646* | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.371) | |||

| L1.∆ Log Real Insur Per Unit | -0.000 | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| ∆ Real Insur Per Unit | 0.025 | -0.023** | |||||

| (0.050) | (0.011) | ||||||

| Time Period | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2019-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 | 2000-24 |

| Avg Level DV | 1396.6 | 1378.4 | 1534.9 | 1364.7 | 1384.4 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

| Obs. | 38692 | 19297 | 14867 | 38326 | 38474 | 38492 | 38474 |

| R-Squared | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Number Zip Codes | 4089 | 3159 | 3059 | 4078 | 4081 | 4085 | 4081 |

| Number Properties | 11176 | 6598 | 5702 | 11142 | 11153 | 11159 | 11153 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CBSA FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. Clustering standard errors by zip code. Dependent variables are the change in log real asking rent in columns 1-3, the change in log real effective rent in column 4, the change in real dollar asking rent in column 5, and an indicator variable for exactly zero change year-over-year in nominal asking rent in columns 6-7. Columns 3 only include observations from 2019-2024. This merged sample only uses property-year observations for which there is both a CMBS operating statement (from Trepp) with non-missing property insurance costs and a non-missing asking rent observation in December of the same year (from RealPage). Other controls include log property built year, log number of units, 7 leads and lags around year of any renovation, log of county employment, log county average weekly wages, annual growth in employment, and annual growth in wages. Real values adjusted by CPI-U, in 2023 dollars.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; RealPage, Inc., Rental Markets data; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

Asking rents tend to be fairly sticky in nominal terms, with about 6 percent of properties in our sample not changing their asking rent from the previous year.9 This nominal rigidity might obscure any influence of insurance costs on asking rents. Indeed, Table 5 shows that landlords are more likely to change asking rent when insurance costs change. Our estimates imply that a 10 percent larger rise in insurance costs reduces the probability that nominal rents won't change by 6 basis points; the dollar specification in column 7 shows that a $10 increase in insurance costs per unit would decrease rent stickiness by about 23 basis points. Overall, although we do see some evidence of effects on asking rents, these correlations are too small to explain the full response of rental revenues to these costs.

Table 5: Relationship Between Growth in Multifamily Insurance Costs and Other Variables

| ∆ Occ | ∆ Maint | ∆ OpEx | ∆ % NOI | ∆ $ NOI | ∆ Yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| ∆ Log Real Insurance Per Unit | 0.001 | 0.025*** | 0.029*** | -0.025*** | -0.264*** | |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.019) | ||

| ∆ Real Insurance Per Unit | -0.738*** | |||||

| (0.036) | ||||||

| Avg Level DV | 94.3 | 102.6 | 645.6 | 778.1 | 761.7 | 8.3 |

| Obs. | 211628 | 230923 | 231997 | 232101 | 232290 | 230816 |

| R-Squared | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Number Zip Codes | 7393 | 7478 | 7485 | 7485 | 7488 | 7479 |

| Number Properties | 61698 | 64794 | 64953 | 65034 | 65024 | 64743 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CBSA FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Other Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. Clustering standard errors by zip code. Dependent variables are the change in log occupied units in column 1, the change in log maintenance expenses in column 2, the change in log of overall operating expenses excluding insurance costs in column 3, the percent change in net operating income (including insurance costs) in column 4, the change in real dollar net operating income in column 5, and the change in rental income yields in columns 6 (calculated as net operating income divided by the property value recorded at loan origination or underwriting). Other controls include log property built year, log number of units, 7 leads and lags around year of any renovation, log of county employment, log county average weekly wages, annual growth in employment, and annual growth in wages. Real values adjusted by CPI-U, in 2023 dollars.

Source: Trepp, LLC. Commercial Real Estate Loan-Level Data; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Authors' analysis.

We can use the same merged sample to examine changes in occupancy rates, as landlords could pursue strategies like increasing advertising or reducing tenant screening to increase revenues by raising occupancy rates. Column 1 of Table 5 shows that there is no significant change in occupancy rates, and the standard error is small enough to rule out any material effect.

The third major component of revenues is rental income for continuing tenants. We do not have data on renewal rates or renewal rents in our sample. Industry reports put renewal rates between 50 and 60 percent during our sample period, which shows that renewals account for a large fraction of rental income.10 The combination of the results above (i.e. noticeable increases in revenue absent any material changes in asking rent or occupancy rates) suggests that landlords increase the rent of continuing tenants in response to rising property insurance costs. It is possible that moving costs make existing tenants less price elastic than new tenants, allowing landlords to pass through cost increases to existing tenants to a greater extent than to new tenants. We hope that future analysis using data on renewal rents as well as asking rents can explore this possibility.

Other Costs

Another way that landlords can adjust to rising property insurance costs is to cut back on other expenses. However, column 2 of Table 5 shows that rising insurance costs are systematically positively related to maintenance and repair expenses. This positive correlation could be the result of reverse causality, as insurance companies will raise premiums in order to offset higher costs of rebuilding, and these rebuilding costs will be strongly related to the maintenance and repair costs faced by property owners. The table also shows a positive correlation with total operating expenses excluding insurance (column 3), which makes sense because maintenance and repair is a large fraction of total costs.

Given this positive relationship, one concern with interpreting the correlations between revenue and property insurance costs is that it could be driven by maintenance and repair costs. Specifically, if maintenance and repair costs rise, that could generate increases in both property insurance costs and property revenues (as owners act to offset these costs). However, when we add maintenance and repair costs as a control in the regressions reported in Table 3, the estimated correlation between insurance costs and revenues does not change (not shown).

Profits

Finally, we combine the results for revenues and costs by looking at the correlation of insurance costs with the landlord's profits. Column 4 of Table 5 shows that a 10 percent increase in insurance costs is associated with a 0.25 percent decrease in net operating income. Meanwhile, a 1 dollar increase in property insurance costs is associated with about 74 cents lower net income (column 5). In other words, the small increases in revenue that landlords achieve when property insurance costs increase is not nearly enough to offset the entire cost increase.

One way to assess the magnitude of the effect on net operating income is to examine the correlation of insurance costs with rental yields, which is defined as current net operating income divided by the property value underwritten at mortgage origination. Column 6 of Table 5 shows that each 10 percent increase in insurance costs decreases rental yields by 2.64 basis points. Using this coefficient, the average increase in insurance costs from 2019 to 2014 (77 percent) would be consistent with a 20 basis point lower rental yield. Although this magnitude is fairly small compared to the average rental yield in the sample of 8.1 percent, it could still be meaningful for property owners. As apartment buildings are re-appraised or sold, it is possible that these insurance cost increases will be capitalized into lower property values.

Conclusion

Property insurance costs for apartment buildings have increased materially in real terms since 2019. We found that nearly three quarters of these costs are borne by landlords and result in lower profits. This pass-through is not dollar for dollar because rental income does appear to increase somewhat in response to higher insurance costs. This increase in revenue appears not to be related to changes in asking rents or occupancy rates, and therefore seems likely to reflect an increase in the rents paid by continuing tenants. Further work should examine why tenants bear so little of these cost increases; why these costs seem to have different effects on average rents on existing tenants and asking rents on new tenants; and how increases in these costs affect property values and housing supply in the longer-run.

References

Bipartisan Policy Center (2024), "Rising Insurance Costs and the Impact on Housing Affordability,".

Blonz, J. A., Hossain, M., & Weill, J. (2024). Pricing protection: Credit scores, disaster risk, and home insurance affordability. Working Paper.

CBRE (2024), "Insurance Costs Depress Multifamily Values," see https://www.cbre.com/insights/briefs/insurance-costs-suppress-multifamily-values-most-in-certain-sun-belt-markets.

CoStar (2024), "Here's How Some Apartment Pros May Deal With Higher Interest Rates, Insurance Costs ," see https://www.costar.com/article/1944537338/heres-how-some-apartment-pros-may-deal-with-higher-interest-rates-insurance-costs.

Damast, D., Kubitza, C., & Sørensen, J. A. (2025). Homeowners insurance and the transmission of monetary policy. Working Paper.

Eastman, E., Kim, K., & Zhou, T. (2024). Homeowners insurance and housing prices. Working Paper.

Fannie Mae Multifamily Economic and Market Commentary (2024), "Higher Insurance Premiums Continue to Impact the Multifamily Sector," see https://www.fanniemae.com/media/51396/display.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2025), "Rising property insurance costs stress multifamily housing,".

Gallin, J. & Verbrugge, R. (2019). A theory of sticky rents: Search and bargaining with incomplete information. Journal of Economic Theory 183: 478-519.

Gallin, J., & Verbrugge, R. 2017. Sticky Rents. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Working Paper.

Ge, S., Johnson, S., & Tzur-Ilan, N. (2025). Climate risk, insurance premiums and the effects on mortgage and credit outcomes.

Ge, S., Lam, A., & Lewis, R. (2022). The effect of insurance premiums on the housing market and climate risk expectations. Working Paper.

JP Morgan (2025), "3 tips to lower your commercial real estate insurance costs," see https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/real-estate/commercial-real-estate/commercial-real-estate-investment-insurance-explained.

Kalda, A., Sharma, V., Soni, V., & Wenning, D. (2025). Beyond the storm: Climate risk and homeowners' insurance. Working Paper.

Keys, B. J., & Mulder, P. (2024). Property insurance and disaster risk: New evidence from mortgage escrow data. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper.

Kim, M., Mahajan, P., & Wang, Z. (2025). The rise in insurance costs for commercial properties: Causes, effects on rents, and the role of owners.

National Apartment Association (2023), "Rental Housing Insurance Costs Skyrocket,".

RealPage Analytics Blog (2020), "Apartment Lease Renewal Rates Continue to Climb," see https://www.realpage.com/analytics/apartment-lease-renewal-rates-continue-climb/.

RealPage Analytics Blog (2023), "Insurance Costs Have More Than Doubled in the Apartment Sector," see https://www.realpage.com/analytics/rising-insurance-costs-apartment-sector/.

RealPage Analytics Blog (2024), "Apartment Retention Rates Surge," see https://www.realpage.com/analytics/retention-climbs-october-2024/.

Sastry, P., Sen, I., Tenekedjieva, A.-M., & Scharlemann, T. C. (2024). Climate risk and the us insurance gap: Measurement, drivers and implications. Working Paper.

Trepp Multifamily (2023), "Breaking Down Multifamily Property Operating Expenses Across the U.S. Part 3 – Property Insurance," see https://www.trepp.com/access-trepp-multifamily-property-expense-report-august-2023-part-3.

Urban Land Institute (2024), "Insurance on the Rise,".

Yardi Matrix (2024), "Multifamily Expenses Rising, Led by Insurance," see https://www.yardimatrix.com/publications/download/file/5352-MatrixResearchBulletin-MultifamilyExpenses-March2024?utm_source=WhatCountsEmail&utm_medium=Yardi%20Matrix%20Rental%20Market%20-%20Multifamily%20Outlook&utm_campaign=040324_SpecialBulletin_MF_Expenses_23197.

1. Email: Hughes, [email protected]; Molloy, [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Federal Reserve Board, or the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. Keys & Mulder (2024); Sastry et al. (2024); Eastman et al. (2024); Blonz et al. (2024); Ge et al. (2024); Kalda et al. (2025); Damast et al. (2025); Ge et al. (2025). Return to text

3. Industry analysis of multifamily property insurance costs includes: Trepp Multifamily (2023); CBRE (2024), JP Morgan (2025); CoStar (2024); Yardi Matrix (2024); RealPage Analytics Blog (2023); Bipartisan Policy Center (2024); Urban Land Institute (2024); National Apartment Association (2023); Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2025); and Fannie Mae Multifamily Economic and Market Commentary (2024). Return to text

4. Note that this excludes statements where the period covers less than a year, where the financial statements end in a month other than December, and cases where statements have been normalized (based on CREFC Investor Reporting Instructions these normalizations involve excluding temporary or one-time revenue or expense items). Return to text

5. For data cleaning purposes, we study annual statements where insurance costs are reported as greater than $0, where property revenues per unit are between $100 and $10,000, and where insurance costs are greater than 0 and less than 100% of revenues. For other variables, we trim the distribution by year at the 0.5 and 99.5 percentile. Return to text

6. The Fannie Mae Multifamily servicing guide is an example of how multifamily insurance is treated: grouping insurance costs for wind, flood, and earthquake together under property insurance & catastrophic risks. Fannie Mae Delegated Underwriting Service Guide, see https://mfguide.fanniemae.com/node/4226?section=4451. Return to text

7. The increase in average rents is taken as the coefficients from columns 6 and 7 times the increase in average real insurance costs per unit: (68.4-38.7)*.394 = 11.7; (68.4-38.7)*.247 = 7.3. Return to text

8. Landlords can also raise revenues from parking, laundry, vending, or other fees. We find that these sources are very small relative to revenue from rental income. Return to text

9. The evidence of nominal stickiness is consistent with Gallin & Verbrugge (2019) and Gallin & Verbrugge (2017), who use data from the CPI Housing Survey from 1998 to 2008. However, they find a much greater degree of stickiness than we do—about half of units in their sample do not change rent over a 12-month period. This may be due to differences in the sample: our data is asking rent for units averaged by property, while theirs is a survey at the unit-level. Return to text

10. See Real Analytics Blog (2024); RealPage Analytics Blog (2020). Return to text

Hughes, Samuel K., and Raven Molloy (2025). "Rising Property Insurance Costs and Pass-Through to Rents for Apartment Buildings," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 19, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3922.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.