FEDS Notes

August 04, 2023

Financial Flows to the United States in 2022: Was There Fragmentation?1

Events of the last five years, such as the U.S.-China trade war, the COVID-19 pandemic, and—most recently—Russia's invasion of Ukraine, have raised concerns in the popular press and among policymakers that the international economic and financial system is at risk of becoming significantly fragmented (Aiyar et al., 2023; Ip, 2023; Shin, 2023). Most recently, attention has shifted to the possibility of fragmentation along geopolitical lines, where countries primarily trade with and invest in other countries with which they share close diplomatic and political ties (International Monetary Fund, 2023a,b). For the U.S., these fragmentation fears often focus on concerns about the willingness of investors in emerging market economies (EMEs) to hold U.S. assets (and U.S. dollar-denominated assets more broadly).

In this note, I discuss purchases of U.S. securities by foreign official and private investors in 2022 as reported by the Treasury International Capital (TIC) system—the primary data source on foreign demand for U.S. securities—and find little evidence of financial fragmentation through this channel.2 I focus on investors in countries (in particular China, India, and many countries in the Middle East) that have received attention for having heightened geopolitical tensions with the U.S. following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, or increased economic ties with Russia, or greater willingness to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar.3 Investors in these countries were among the largest purchasers of U.S. securities in 2022.4 Moreover, purchases by these countries were not just large compared to flows from other countries, but also large relative to their own purchases of U.S. securities in recent years. The behavior of financial flows to the U.S. in 2022 suggests that financial fragmentation has been quite limited to date, at least for foreign holdings of U.S. securities.5

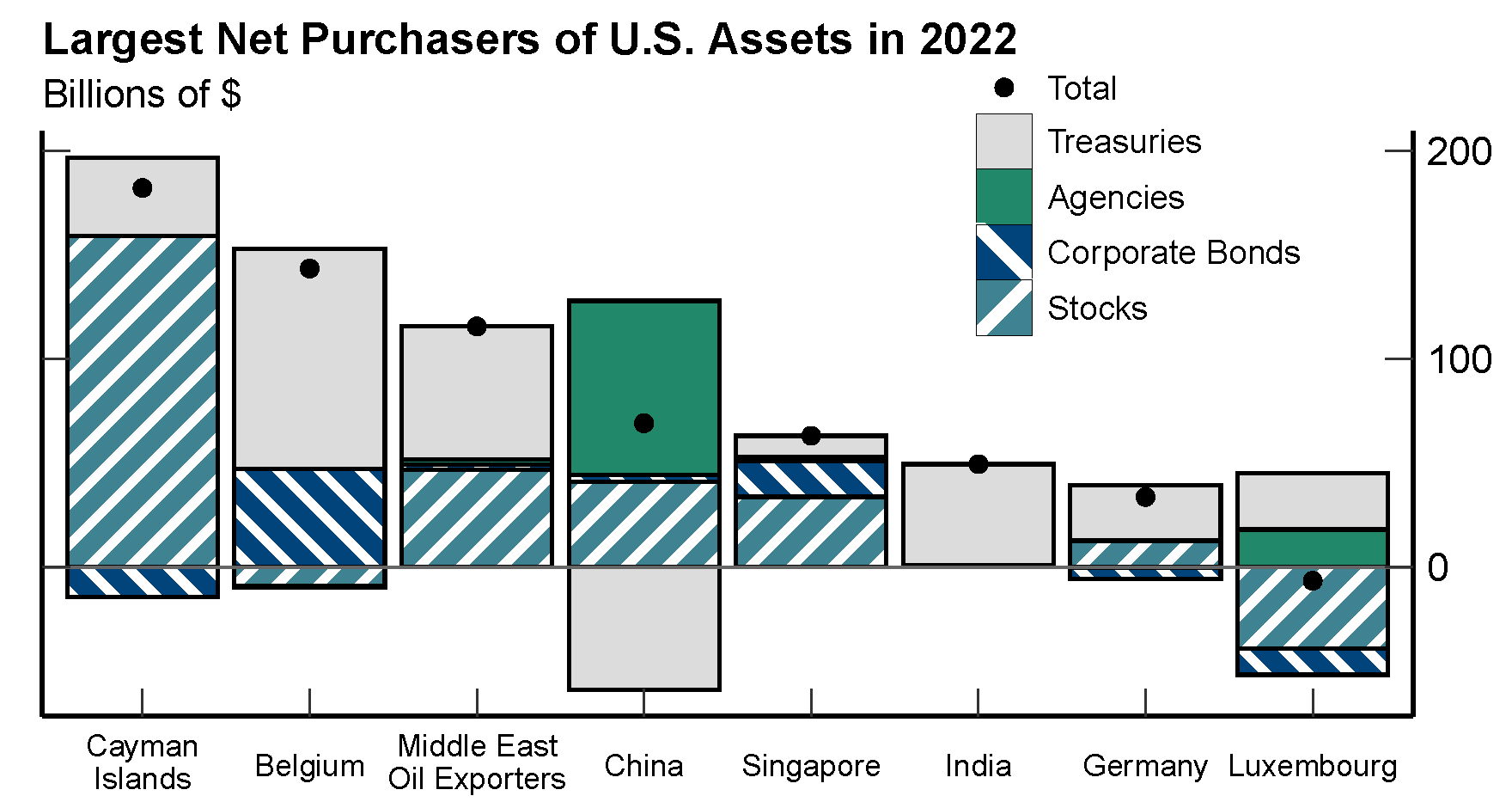

Foreign purchases of U.S. securities were significant in 2022 and sometimes came from "unexpected" locations

In 2022, foreign investors purchased nearly $670 billion of long-term U.S. securities and short-term Treasury bills. As shown in Figure 1, investors in countries that experienced heightened geopolitical tensions with the U.S. in 2022, or countries that—at a minimum—expressed further desire to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar, were among the largest purchasers of U.S. securities last year, specifically China, India, and the Middle East oil exporters.6 7 For China and India, these purchases came despite deepening economic ties to Russia—which was subjected to numerous additional U.S. sanctions in 2022—through greater imports of Russian fuel, and, in the case of China, strengthened political ties following the declaration of a "no-limits" partnership with Russia.8 Moreover, geopolitical relations between China and the U.S. appeared to deteriorate further in 2022, especially after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's visit to Taiwan (Kuo et al., 2022). Some Middle East oil exporters reportedly experienced strained relations with the U.S. in 2022, and the United Arab Emirates became an important intermediary for Russian oil exports.9 If widespread financial fragmentation was occurring, one would not expect these countries to make large purchases of U.S. securities. Finally, while central banks in many of these countries also reportedly made net purchases of gold in 2022, these gold purchases were significantly smaller in dollar terms relative to the purchases of U.S. securities reported here (World Gold Council, 2023).10

Note: Middle East oil exporters are Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE.

Source: Staff estimates using Treasury International Capital data.

Moreover, the reported purchases by potential geoeconomic diversifiers may understate these countries' true purchases of U.S. securities in 2022. Some of the large purchases of U.S. securities in 2022 attributed to Belgian residents, as shown in Figure 1, likely reflect purchases by ultimate investors in other countries. Euroclear, a major global securities custodian, is based in Belgium, so holdings of U.S. securities attributed to Belgium often belong to residents of other foreign countries who custody these securities with Euroclear (Bertaut and Judson, 2014). For example, Setser (2016) notes that the TIC data may understate China and Saudi Arabia's true holdings of U.S. dollar assets, but that combining Belgium's holdings of U.S. Treasury securities with China's holdings helps match both the size of China's estimated U.S. dollar FX reserves and the timing of changes in these FX reserves. Thus, it is plausible that some of the Belgian purchases estimated in 2022 actually came from Chinese investors and perhaps investors in some of the other countries discussed above.

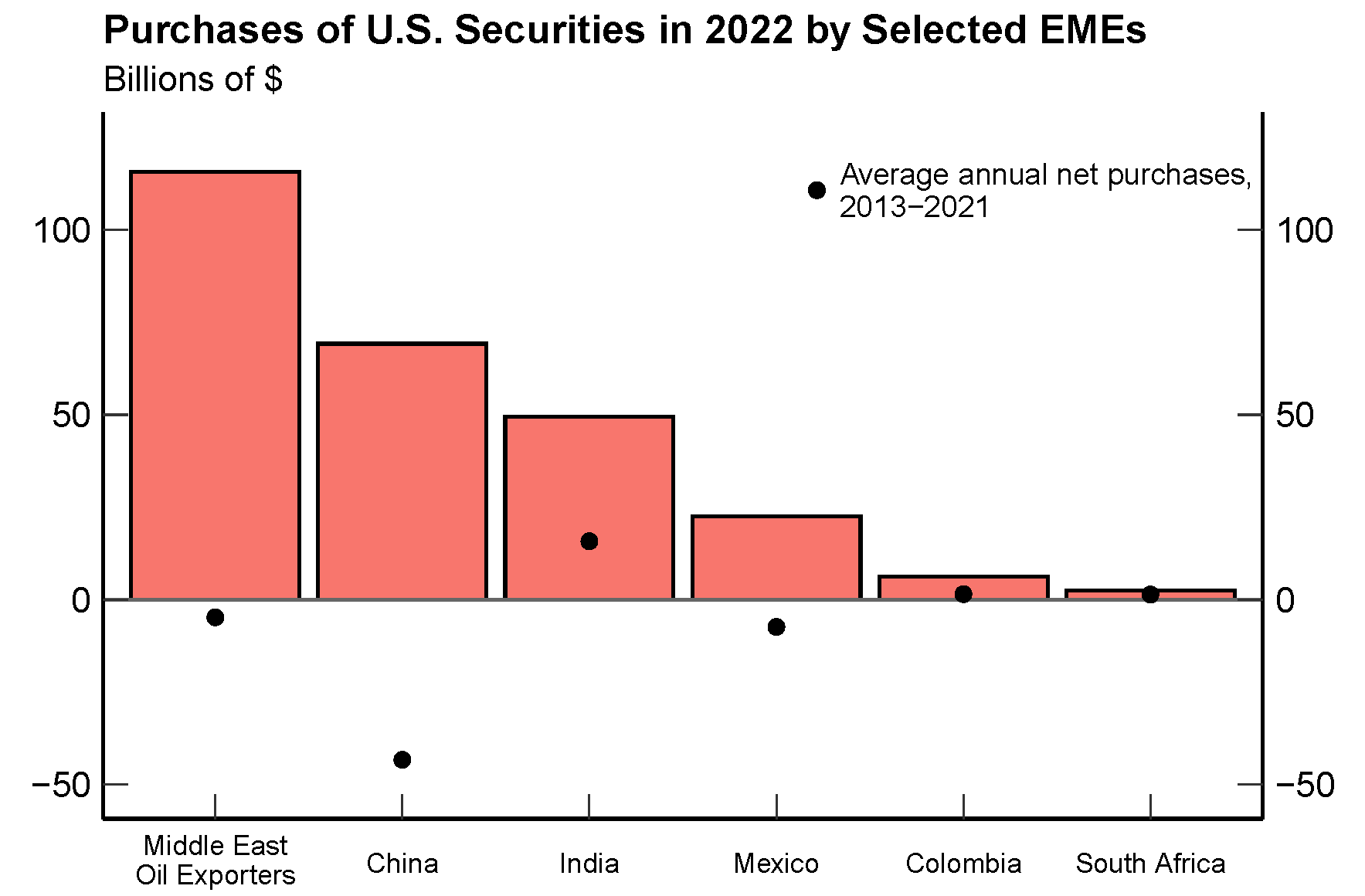

Purchases of U.S. securities by China, India, and Middle East oil exporters in 2022 also large compared to their prior purchases.

Not only were the purchases by China, India, and the Middle East oil exporters in 2022 large compared to those by other countries, they were also sizable when measured against these countries' average purchases over the previous nine years. As shown in Figure 2, net purchases in 2022 were well above average annual net purchases from 2013-2021 in every case. Additionally, for India and the Middle East oil exporters, purchases of U.S. securities in 2022 were not just above average but the highest ever. Moreover, these record purchases of U.S. securities by investors in India and the Middle East came despite limited overall FX reserve accumulation or even FX reserve sales by these countries in 2022. Thus, the lack of foreign exchange reserve accumulation in 2022 by some of these countries does not necessarily reflect a diminished interest in U.S. securities.11 As before, under increased financial fragmentation, one would not expect these countries to be making larger purchases of U.S. assets compared to purchases in previous years.

Note: Middle East oil exporters are Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE.

Source: Staff estimates using Treasury International Capital data.

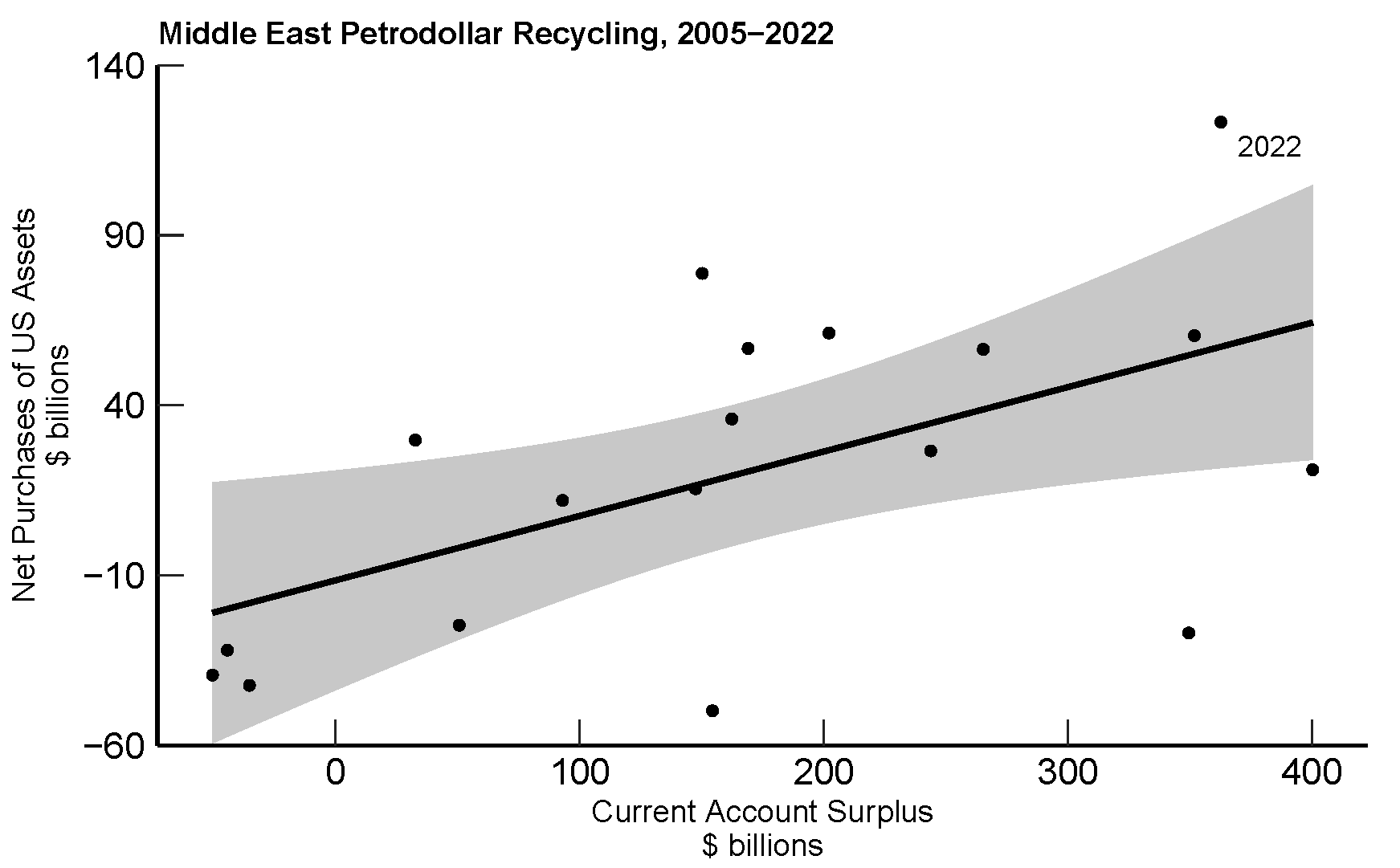

One qualification is that, for China and the Middle East oil exporters, current account surpluses were significantly larger in 2022 than in previous years. Since current account surpluses are equivalent to net capital outflows, this would suggest that the larger purchases of U.S. securities by China and the Middle East oil exporters in 2022 were simply the mirror of their larger current account surpluses. That is, geopolitical tensions could still have weighed on financial flows to the U.S. from these countries. The data do not necessarily support this argument, however. As shown in Figure 3, purchases of U.S. securities by Middle East oil exporters in 2022 were still quite large when compared to purchases in other years since 2005 when these countries had similarly large current account surpluses. Current account balances likely play some role in determining which countries purchase U.S. securities, but the large purchases by the Middle East oil exporters in 2022 still stand out even after accounting for their large current account surpluses.

Note: 2022 current account balance is projection based on April 2023 WEO. Includes data for Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE. Black line is fitted values from regression of net purchases of U.S. securities on current account surpluses. Shaded area is 95% confidence region.

Source: Staff estimates using Treasury International Capital data, IMF WEO.

A large current account surplus in China also does not necessarily guarantee large purchases of U.S. securities by Chinese investors. Chinese annual current account surpluses returned to more elevated levels three years ago, beginning in 2020 (far surpassing the 2010-2019 annual average), and approaching record levels in 2022. Yet, over the past three years, Chinese investors purchased U.S. securities only in 2022, despite the heightened geopolitical tensions.

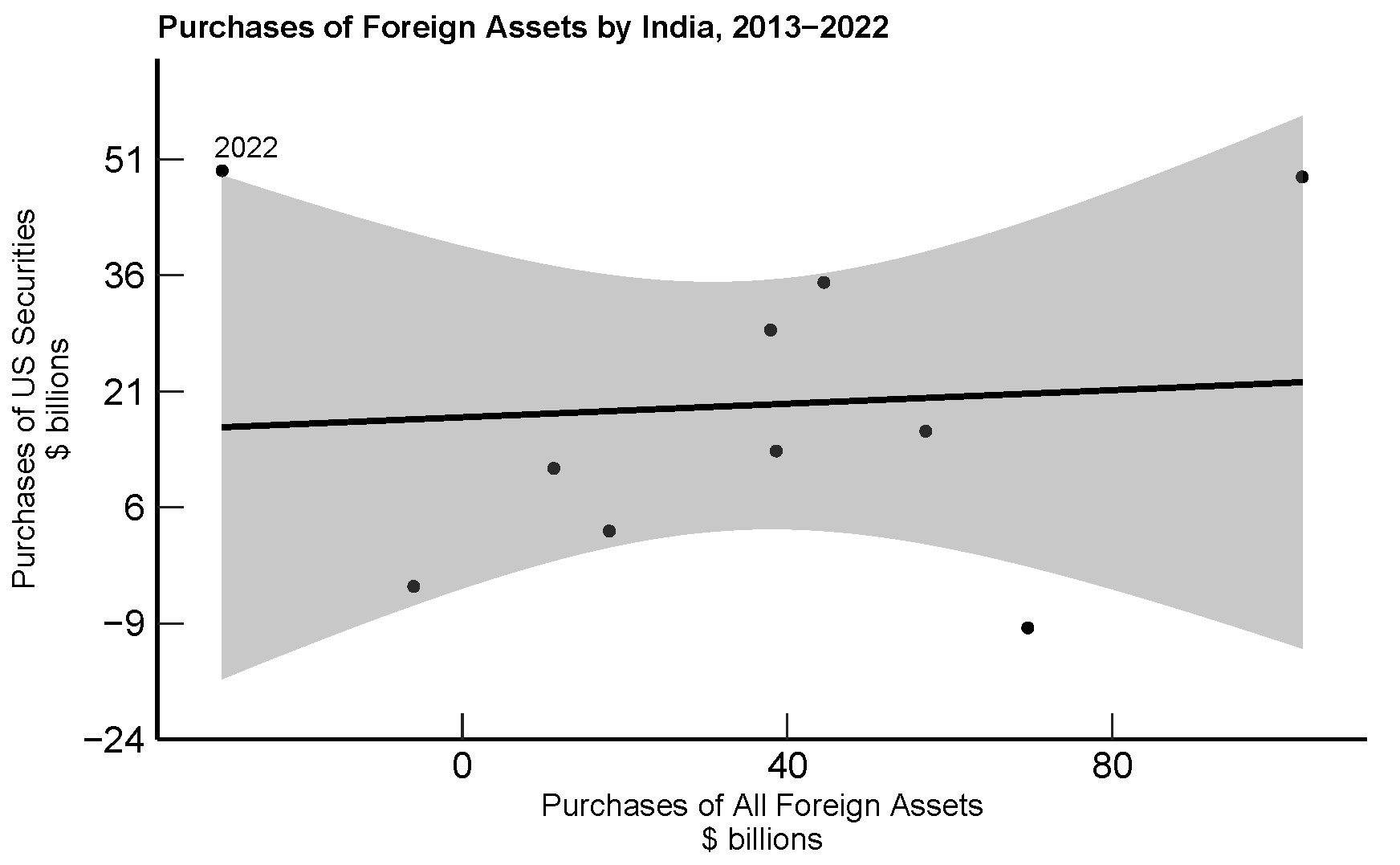

Although India consistently runs current account deficits (accruing an especially large deficit in 2022), one still needs to consider whether its net purchases of U.S. securities in 2022 might have reflected broader developments in Indian investors' purchases of foreign securities. To do so, I compare purchases of U.S. securities by Indian investors (as reported in the TIC data) to combined gross portfolio outflows and official reserve asset accumulation for each of the past ten years in Figure 4. By this benchmark, Indian purchases of U.S. securities in 2022 are exceptionally notable, as Indian investors actually sold foreign securities on net in 2022. Thus, the large purchases of U.S. securities by Indian investors in 2022 were not part of a broader set of purchases of foreign securities.

Note: Indian purchases of all foreign assets are the sum of gross portfolio outflows and official reserve asset transactions as reported in the balance of payments. Black line is fitted values from regression of net purchases of U.S. securities on total purchases of foreign assets. Shaded area is 95% confidence region.

Source: Staff estimates using Treasury International Capital data and Haver

Purchases of U.S. securities by other EMEs also relatively large in 2022

The phenomenon of relatively large purchases of U.S. securities (when compared to those of recent years) in 2022 was not limited to China, India, and the Middle East oil exporters. Figure 2 additionally shows that Colombia and South Africa also had purchases of U.S. securities in 2022 above their recent historical averages, with purchases by Colombia at historical highs.12 These purchases are notable as both countries possibly showed signs of drifting away from the U.S. geopolitically in 2022.13 Under the administration led by Iván Duque, Colombia had pledged to help train Ukrainian troops for landmine removal in May 2022 (Orru, 2022). Following Gustavo Petro's ascension to the presidency, Colombia's rhetoric on Ukraine shifted to a more neutral stance, and Petro refused to send Russian-made weapons to Ukraine in early 2023 (Quesada, 2022; Stott et al., 2023). South Africa participated in joint military exercises with Russia and China during the one-year anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine (du Plessis, 2023). If geopolitics were a major factor driving financial flows to the U.S., these net purchases would likely not have occurred.

Differences in data coverage lead to slightly different conclusions about fragmentation in other recent work

Other recent work finds greater geopolitical distance between countries is associated with a reduction in cross-border portfolio investment (International Monetary Fund, 2023a). Such a finding seems at odds with the facts reported in this note, so it is important to discuss what may be behind this discrepancy. First, I report net purchases by all investors—both private and official sector purchases, while International Monetary Fund (2023a) studies private sector allocations, sometimes focusing only on investment fund allocations and at other times reporting results for all private portfolio investments. For the U.S. and other advanced economies that receive substantial cross-border inflows from foreign official (government) investors, it is important to consider both private and official investors, as official investors are responsible for nearly a quarter of all cross-border portfolio holdings of U.S. securities.14

Second, there are also differences in the data on private sector investors between this note and International Monetary Fund (2023a) that could result in different conclusions about geoeconomic fragmentation. International Monetary Fund (2023a) primarily analyzes investment fund allocations, but these funds are a subset of the overall investor base, and their importance for total portfolio investment varies across countries. This can limit our ability to draw broader conclusions about geopolitics and financial fragmentation from analysis of this sector. While the use of the IMF's coordinated portfolio investment survey (CPIS) data ameliorates this concern, the CPIS can also be limited by countries' voluntary participation in this survey. For example, many of the Middle East oil exporters discussed in this note do not report their cross-border holdings in CPIS. In contrast, reporting on all cross-border securities holdings in the TIC system is mandatory for all U.S.-resident custodians.15 Thus, while this note only discusses foreign portfolio investments in the U.S., it analyzes the most comprehensive data available on these investments and finds little evidence of fragmentation along geopolitical lines.

References

Aiyar, Shekhar, Ilyina, Anna, and others (2023). "Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism," Staff Discussion Note SDN/2023/001. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Bertaut, Carol, Beau Bressler, and Stephanie Curcuru (2019). "Globalization and the Geography of Capital Flows," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 6, 2019 https://doi.org.10.17016/2380-7172.2446.

Bertaut, Carol, and Ruth Judson (2014). "Estimating U.S. Cross-Border Securities Positions: New Data and New Methods," International Finance Discussion Papers 1113. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/ifdp/estimating-us-cross-border-securities-positions-new-data-and-new-methods.htm.

Bertaut, Carol and Ruth Judson (2022). "Estimating U.S. Cross-Border Securities Flows: Ten Years of the TIC SLT," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 18, 2022, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3068.

Deng, Chao, Ann M. Simmons, Evan Gershkovich, and William Mauldin (2022). "Putin, Xi Aim Russia-China Partnership Against U.S.," Wall Street Journal, February 4.

du Plessis, Carien (2023). "South Africa's Naval Exercise with Russia, China Raises Western Alarm" Reuters, February 18.

Economist Intelligence Unit (2023). "Russia's Pockets of Support Are Growing in the Developing World," The EIU Update, https://www.eiu.com/n/russias-pockets-of-support-are-growing-in-the-developing-world/, March 7, 2023.

Faucon, Benoit and Rory Jones (2022). "Russian Cash and Trade Drawn to Dubai by Low Taxes, No Sanctions," Wall Street Journal, June 1.

International Monetary Fund (2023a). Global Financial Stability Report: Safeguarding Financial Stability amid High Inflation and Geopolitical Risks. Washington, DC, April.

International Monetary Fund (2023b). World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery. Washington, DC, April.

Ip, Greg (2023). "In Davos, Leaders Fret over Fragmenting Global Economy," Wall Street Journal, January 18.

Kalin, Stephen, Summer Said, and Dion Nissenbaum (2022). "U.S.-Saudi Relations Buckle, Driven by Animosity Between Biden and Mohammed bin Salman," October 24.

Kuo, Lily, Erin Cunningham, Yasmeen Abutaleb, Rachel Pannett, and Annabelle Timsit (2022). "Nancy Pelosi Departs Taiwan, Ending Contentious Visit that Angered China," Washington Post, August 3.

Lawler, Alex (2023). "Russian Crude Oil Heads to UAE as Sanctions Divert Flows," Reuters, March 6.

Menon, Shruti (2022). "Ukraine Crisis: Who Is Buying Russian Oil and Gas?" BBC, December 6.

Nissenbaum, Dion, Stephen Kalin, and David S. Cloud (2022). "Saudi, Emirati Leaders Decline Calls with Biden During Ukraine Crisis," Wall Street Journal, March 8.

Ohri, Nikunj Rajesh and Shivangi Acharya (2022). "India Rupee Settlement Mechanism Draws Interest from More Nations," Reuters, December 16.

Orru, Mauro (2022). "Colombia to Train Ukrainian Military in Landmine Removal," Wall Street Journal, May 24.

Quesada, Juan Diego (2022). "Colombia's Petro Calls for Peace Negotiations to End the War in Ukraine," El País, September 21.

Sen, Sudhi Ranjan, Adrija Chatterjee, and Rakesh Sharma (2023). "India's Soaring Russian Oil Imports Render Rupee Trade Futile," Bloomberg, February 13.

Setser, Brad W. (2016). "A Bit More on Chinese, Belgian, and Saudi Custodial Holdings," Follow the Money, https://www.cfr.org/blog/bit-more-chinese-belgian-and-saudi-custodial-holdings, June 20, 2016.

Setser, Brad W. (2022). "The New Geopolitics of Global Finance," Follow the Money, https://www.cfr.org/blog/new-geopolitics-global-finance, November 30, 2022.

Shin, Hyun Song (2023). "Global Value Chains under the Shadow of Covid," presentation at the Columbia University CFM-PER Alternative Data Initiative virtual seminar, February 16.

Stott, Michael, Christine Murray, Lucinda Elliott, Carolina Ingizza, and Guy Chazan (2023). "'We Are for Peace': Latin America Rejects Pleas to Send Weapons to Ukraine," Financial Times, February 15.

Verma, Nidhi (2022). "Russia Seeking Oil Payments from Indian in Dirhams," Reuters, July 18.

World Gold Council (2023). "Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2022: Central Banks," Technical Report, https://www.gold.org/goldhub/research/gold-demand-trends/gold-demand-trends-full-year-2022/central-banks.

Appendix

Table 1. All countries within this group, except Bahrain, purchased U.S. securities on net in 2022

| Country | Net Purchases |

|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 52.5 |

| United Arab Emirates | 34.8 |

| Iraq | 20 |

| Kuwait | 7.7 |

| Qatar | 5.9 |

| Oman | 3.1 |

| Bahrain | -0.7 |

Table 2. The shares of foreign holdings of U.S. securities belonging to investors

| Country | 2022 Share | 2021 Share |

|---|---|---|

| China | 5.96 | 5.59 |

| India | 0.98 | 0.75 |

| Middle East Oil Exporters | 3.65 | 3.27 |

1. I thank Shaghil Ahmed, Daniel Beltran, Carol Bertaut, and Alexandra Tabova for helpful comments and suggestions. Jialin Zhang provided excellent research assistance. Return to text

2. The TIC data inform the official quarterly balance of payments statistics published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The estimated flows are essentially constructed using changes in foreign holdings of U.S. securities adjusted for valuation effects as discussed in Bertaut and Judson (2014, 2022). Return to text

3. Although Russia would be a natural case to study for heightened geopolitical tensions with the U.S. in 2022, I exclude Russia from the analysis because the sanctions imposed on the Central Bank of Russia and other Russian financial institutions in 2022 make it impossible—or, at the very least, extremely difficult—for Russian investors to purchase U.S. securities. Return to text

4. Ideally, one would also examine net purchases of foreign securities by U.S. investors in 2022 for evidence of fragmentation, but analysis of these flows is complicated by a couple of factors. First, many countries, including most EMEs, experienced a decline in portfolio inflows in 2022 for reasons unrelated to geoeconomic fragmentation. Second, many firms in EMEs issue securities using a subsidiary or financing arm located outside of the home country. Cross-border statistics based on the legal residence of the firm (such as the TIC data) do not consider these as flows to the home country (Bertaut, Bressler, Curcuru, 2019). Accounting for these factors goes beyond the scope of this note. Return to text

5. Relatedly, Setser (2022) expresses skepticism about the amount of financial fragmentation or "friendshoring" that can take place given the distribution of current account balances across geopolitical lines. Return to text

6. Middle East oil exporters refers to Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Table 1 in the Appendix shows that all countries within this group, except Bahrain, purchased U.S. securities on net in 2022. Return to text

7. Table 2 in the Appendix shows that the shares of foreign holdings of U.S. securities belonging to investors in each of these countries also increased in 2022. Return to text

8. See Menon (2022), for example, on China and India's growing imports of Russian fuel. Several Middle Eastern oil exporters also reportedly increased imports of Russian oil in 2022 (Lawler, 2023). While oil trade between countries is often settled in U.S. dollars, the Indian government has been working on a system to pay for its oil imports using Indian rupees to reduce demand for U.S. dollars (Sen et al., 2023; Ohri and Acharya, 2022). The Chinese and Russian governments released a joint statement on February 4, 2022 in part declaring their countries shared a friendship with "no limits" (Deng et al., 2022). Return to text

9. On possible strains in relations between the U.S., Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates see Nissenbaum et al. (2022) and Kalin et al. (2022). The United Arab Emirates' role in facilitating Russian oil exports includes the use of the dirham by other countries to pay for Russian oil and as a location for Russian companies' international operations (Verma, 2022; Faucon and Jones, 2022). Return to text

10. According to the World Gold Council report, China added 62 tons to its gold reserves, Qatar added 35 tons, Iraq added 34 tons, India added 33 tons, the United Arab Emirates added 25 tons, and Oman added 2 tons (World Gold Council, 2023). Even if one assumes that all gold was purchased at its 2022 high price, the dollar amount of gold purchased is significantly below total investor purchases of U.S. securities in 2022. Return to text

11. Instead, with over 40 percent of the overall purchases of U.S. securities by Middle East oil exporters taking the form of purchases of U.S. equities (Figure 1), it is likely that their demand for U.S. securities came more from sovereign wealth funds rather than central banks. Return to text

12. Figure 2 also includes Mexico, which had historically high purchases of U.S. securities in 2022 as well. Return to text

13. Recent analysis by the Economist Intelligence Unit suggests Colombia and South Africa have shifted their stance on Russia's invasion of Ukraine further away from the position of the U.S. and its allies over the course of 2022 ("Russia's Pockets of Support are Growing in the Developing World," March 7, 2023). Return to text

14. Aiyar et al. (2023) consider how geoeconomic fragmentation may affect both private capital flows and official portfolio allocations and do suggest that there are limits to how much official reserves may reallocate away from U.S. dollar assets. Return to text

15. This is not to say the TIC data are not without their challenges, such as the issues created by custodial chains, which may obscure who the ultimate owner of a U.S. security is. Return to text

Weiss, Colin R. (2023). "Financial Flows to the United States in 2022: Was There Fragmentation?," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August 04, 2023, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3322.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.