FEDS Notes

December 01, 2022

Longer-Run Neutral Rates in Major Advanced Economies1

Thiago R.T. Ferreira2 and Carolyn Davin3

With major central banks in the process of tightening monetary policy aggressively, an important question is how far policy rates will rise and where they will settle in the longer run. One reference point often used to evaluate this question is the longer-run neutral policy rate—the policy rate consistent with economic activity at its longer-run potential and inflation at its target. Longer-run neutral rates reflect the many economic factors influencing the level of interest rates over time, such as the underlying pace of productivity growth and demographic trends. In this note, we discuss estimates of neutral rates as reported by major central banks for their own economies and as calculated using the model from Ferreira and Shousha (2021). Overall, the model-based estimates of neutral rates suggest a modest rise in recent years, with these estimates currently near those most recently reported by major central banks.

The table below presents values of longer-run nominal neutral rates that can be gleaned from communications of four major central banks for their economies.4 These neutral rates range from as low as 1 percent for the euro area at the lower end of its range (implying negative real neutral rates) to as high as 3 percent for the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom at the upper end of their ranges. As can be seen from the "Sources" column in the table, central banks differ in their communications about neutral rates. The Bank of Canada (BOC) publishes its estimates for neutral rates annually and cited them in its July post-meeting press conference. The Federal Reserve (Fed) publishes quarterly assessments by participants of the Federal Open Market Committee of longer-run policy rates as part of its Summary of Economic Projections. We interpret the median of these assessments as a measure of the longer-run neutral rate communicated by the Committee.5 In contrast, neutral rate estimates by the European Central Bank (ECB) have only appeared in speeches given by individual Governing Council members. The Bank of England (BOE) has avoided neutral rates in its recent communications, and some BOE officials have expressed skepticism about the usefulness of the neutral rate concept for real-time policymaking.6

Table 1: Estimates of Major Central Banks' Longer-Run Nominal Neutral Rates

| Central bank | Estimates (percent) | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Federal Reserve | 2.3 to 3 | Summary of Economic Projections, September 2022. |

| Bank of Canada | 2 to 3 | Staff estimates, April 2022. Public analytical note. |

| European Central Bank | 1 to 2 | Speeches from Governing Council members. |

| Bank of England | 2 to 3 | Staff estimates, August 2018. Inflation report. |

Source: Federal Reserve estimates are from the September 2022 Summary of Economic Projections, which is available on the Board's website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20220921.pdf. Bank of Canada estimates are from Faucher and others (2022). European Central Bank estimates are from Galhau (2022), with these numbers also consistent with and Lane (2022). Bank of England estimates are from Bank of England (2018).

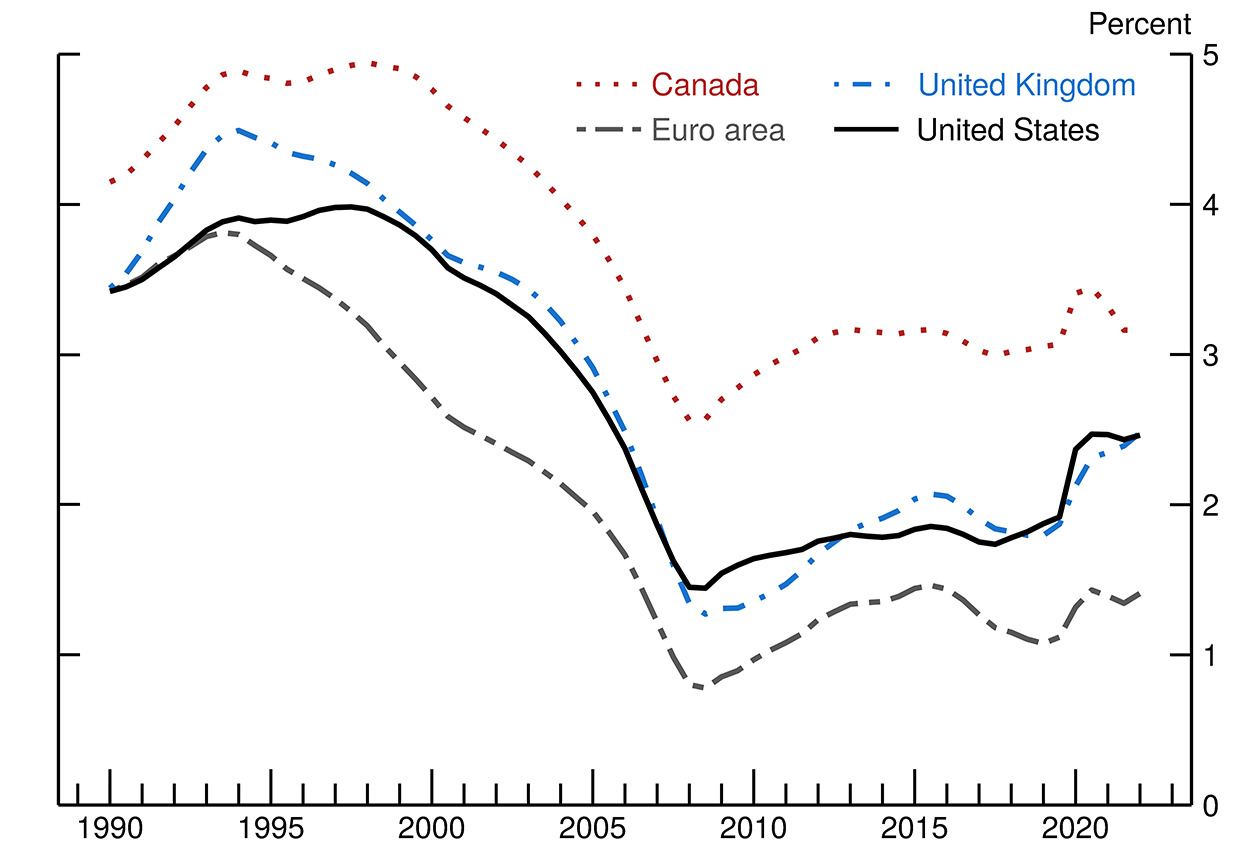

To provide model-based measures of longer-run neutral nominal rates, we use the model from Ferreira and Shousha (2021).7 Addressing policymakers' concerns that different economic drivers may push neutral rates in different directions (for example, Gopinah, 2022), the model accounts for the following economic drivers: the supply of sovereign debt, demand for safe assets, trends in productivity growth, demographic changes, and global spillovers in the determination of neutral rates. The model estimates show that neutral rates in the advanced economies (AEs) increased after the Global Financial Crisis and have taken another step up following the pandemic, as shown in figure 1. These increases put the model's neutral rate estimate for Canada slightly above the high end of the BOC's range, while those for the United States, the United Kingdom, and the euro area have risen from the low end to the middle of the ranges communicated by the Fed, the BOE, and the ECB, respectively.

Note: The figure shows nominal neutral interest rates estimated using the model from Ferreira and Shousha (2021) for the United States (black), Canada (red), the euro area (gray), and the United Kingdom (blue). These estimates come from a two-sided Kalman-filter that calculates real neutral rates for each economy and then adds the 2 percent inflation target from each central bank.

Source: Staff estimates.

Table 2 decomposes the changes in neutral rates across countries over the past three decades into contributions from the different economic drivers. Leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, neutral rates in these four economies saw declines of between 2.1 and 2.8 percentage points, with all drivers pushing down neutral rates. Between 2008 and 2019, the positive contribution of the increased sovereign debt supply modestly offset the negative contributions from other drivers. Since the pandemic, the rise in government debt accounts for most of the recent rise in neutral rates in these major AEs, with other factors exerting largely offsetting effects.8 At the country level, the United Kingdom saw the largest increase in neutral rates according to the model estimates since the pandemic, followed by the United States, the euro area, and Canada.

Table 2: Drivers of Changes in Longer-Run Neutral Rates

United States

| 1995-2007 | 2008-19 | 2020-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Change | -2.3 | .2 | .5 |

| Debt Supply | -.4 | 1.4 | .4 |

| Safe Asset Demand | -.7 | -.1 | .1 |

| Productivity | -.1 | .1 | .4 |

| Demographics | .0 | -.3 | -.1 |

| Global Spillovers | -.6 | -.4 | -.2 |

| Other Factors | -.5 | -.4 | .0 |

Canada

| 1995-2007 | 2008-19 | 2020-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Change | -2.1 | .3 | .1 |

| Debt Supply | -.4 | 1.4 | .4 |

| Safe Asset Demand | -.7 | -.1 | .1 |

| Productivity | -.6 | .2 | -.5 |

| Demographics | .1 | -.4 | -.1 |

| Global Spillovers | -.1 | -.4 | .2 |

| Other Factors | -.5 | -.4 | .0 |

Euro Area

| 1995-2007 | 2008-19 | 2020-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Change | -2.7 | .1 | .3 |

| Debt Supply | -.4 | 1.4 | .4 |

| Safe Asset Demand | -.7 | -.1 | .1 |

| Productivity | -.9 | -.2 | -.1 |

| Demographics | .0 | -.4 | -.1 |

| Global Spillovers | -.4 | -.3 | .1 |

| Other Factors | -.3 | -.3 | -.1 |

United Kingdom

| 1995-2007 | 2008-19 | 2020-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Change | -2.8 | .2 | .6 |

| Debt Supply | -.4 | 1.4 | .4 |

| Safe Asset Demand | -.7 | -.1 | .1 |

| Productivity | -1.0 | -.2 | .4 |

| Demographics | .0 | -.2 | -.1 |

| Global Spillovers | -.6 | -.4 | -.2 |

| Other Factors | -.2 | -.2 | .0 |

Note: The tables decompose the changes in neutral interest rates for the United States, Canada, the euro area, and the United Kingdom.

Source: Board staff calculations.

That said, factors not considered in this model may be currently exerting downward pressure on longer-run neutral rates. For instance, the economic effects from the war in Ukraine may be interpreted as a terms-of-trade shock, in which import prices—those of energy and traded goods—have risen significantly, raising the cost of living and reducing real incomes. To the extent that these changes become persistent, the war may decrease neutral rates similarly to a negative productivity shock. Additionally, the heightened uncertainty about the economic outlook—given the many geopolitical, economic, and climate-related crosscurrents buffeting the global economy—may cause consumers and firms to become more cautious. By depressing investment demand and increasing precautionary savings, such uncertainty may also depress neutral rates.

All told, while the sharp rise in government indebtedness since the pandemic may have put upward pressure on neutral rates abroad, we estimate that this pressure has been likely modest. Importantly, the neutral rate estimates discussed here help us understand where policy rates may converge to in future years.

References

Bank of England (2018). Inflation Report. London: BOE, August, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/inflation-report/2018/august/inflation-report-august-2018.pdf?la=en&hash=07356C865A7416716C85C54FD7F752BF9DF0E19B.

Faucher, Guyllaume, Christopher Hajzler, Martin Kuncl, Dmitry Matveev, Youngmin Park, and Temel Taskin (2022). "Potential Output and the Neutral Rate in Canada: 2022 Reassessment," Staff Analytical Note 2022-3. Ottawa: Bank of Canada, April, https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/san2022-3.pdf.

Ferreira, Thiago R.T., and Samer Shousha (2021). "Supply of Sovereign Safe Assets and Global Interest Rates," International Finance Discussion Papers 1315. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/ifdp/files/ifdp1315.pdf.

——— (2022), "Determinants of Global Neutral Interest Rates," unpublished paper, https://drive.google.com/file/d/187eWHbzh4gekBORn3GDQIiZ2OkwjRNQs/view.

Galhau, François Villeroy de (2022). "Balancing between Science and Art, Predictability and Reactivity," speech delivered at "Reassessing Constraints on the Economy and Policy," an economic policy symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 27, https://www.kansascityfed.org/Jackson%20Hole/documents/9049/2022.08.27_Jackson_Hole_speech_Fran%C3%A7ois_Villeroy_de_Galhau_final.pdf.

Gopinath, Gita (2022). "How Will the Pandemic and War Shape Future Monetary Policy?" speech delivered at "Reassessing Constraints on the Economy and Policy," an economic policy symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 26, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2022/08/26/sp-gita-gopinath-remarks-at-the-jackson-hole-symposium.

Jordan, Thomas J. (2022). "What Are the Consequences of the War in Ukraine for the SNB's Monetary Policy?" speech delivered at the 114th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders of the Swiss National Bank, April 29, https://www.snb.ch/en/mmr/speeches/id/ref_20220429_tjn/source/ref_20220429_tjn.en.pdf.

Lane, Philip (2022). "The Monetary Policy Strategy of the ECB: The Playbook for Monetary Policy Decisions," speech delivered at the Hertie School, Berlin, March 2, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2022/html/ecb.sp220302~8031458eab.en.html.

Lowe, Philip (2022). "Inflation, Productivity and the Future of Money," speech delivered at the Australian Strategic Business Forum 2022, Melbourne, Australia, July 20, https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2022/sp-gov-2022-07-20.html.

Norges Bank (2022). Monetary Policy Report with Financial Stability Assessment. Oslo: Norges Bank, June, https://www.norges-bank.no/contentassets/5b2b711ec0d643c99a0a84a0e36ab5d2/mpr-2-22.pdf?v=06/28/2022122105&ft=.pdf.

Pill, Huw (2022). "Monetary Policy with a Steady Hand," speech delivered at the Society of Professional Economists Online Conference 2022, February 9, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2022/february/huw-pill-speech-at-the-society-of-professional-economists-annual-conference.

Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2022). "Ongoing Monetary Tightening," news release, August 17, https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/hub/news/2022/08/ongoing-monetary-tightening.

1. The note benefitted from comments by Jasper Hoek, Shaghil Ahmed, and Etienne Gagnon. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the staff, the Board of Governors, or the Federal Reserve Banks. Return to text

2. Division of International Finance, Federal Reserve Board, 20th and C St. NW, Washington, DC 20551. Email: [email protected]. Phone: (202) 973-6945. Return to text

3. Division of International Finance, Federal Reserve Board, 20th and C St. NW, Washington, DC 20551. Email: [email protected]. Phone: (202)-912-4333.Return to text

4. Models of neutral rates typically focus on estimates in real terms; policymakers often cite nominal estimates. Return to text

5. Other central banks have also cited longer-run neutral rates in monetary policy reports (for example, Norges Bank), minutes summarizing discussions in monetary policy meetings (for example, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand), and speeches from members of their voting committees (for example, the Swiss National Bank and the Reserve Bank of Australia). See Norges Bank (2022), Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2022), Jordan (2022), and Lowe (2022). Return to text

6. In a February 2022 speech, BOE chief economist Huw Pill stated that "R-star is not a very meaningful guide or reference for real time monetary policy making"; see Pill (2022). Return to text

7. The calculations presented here use an updated version of the model in Ferreira and Shousha (2022). Return to text

8. For simplicity, in this table we describe as "safe asset demand" the sum of the effects from two drivers presented separately in the paper: the convenience yield and a measure of policy-driven demand for safe assets due to foreign reserve holdings and regulatory requirements. Return to text

Davin,Carolyn, and Thiago Ferreira (2022). "Longer-Run Neutral Rates in Major Advanced Economies," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 01, 2022, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3220.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.