FEDS Notes

December 19, 2017

Stigma and the discount window

Mark Carlson and Jonathan D. Rose1

Introduction

One of the primary roles of central banks like the Federal Reserve is to provide liquidity to the financial system, particularly during periods of stress. The discount window is a critical tool for providing that liquidity. Because banks are able to interact directly with the Fed, the discount window is able to provide liquidity to the banking system even in periods when the interbank market for funds is not operating smoothly. Disruptions to the operation of interbank market may be the result of idiosyncratic factors, or during episodes of financial stress when demand for liquidity is high and market participants are particularly cautious regarding their counterparties.2 It is during periods of stress and heightened demand for liquidity that the ability to add liquidity to the financial system is most important; while banks trade liquidity among themselves, their willingness to do so may be quite limited, and only a central bank can provide additional liquidity and thereby temper the strains. The discount window has been key to the response of the Federal Reserve during some of these stress episodes.

Moreover, even in more normal times, the discount window can be useful in promoting stable conditions in the interbank market for reserve balances. If the cost of obtaining reserve balances in the market becomes particularly expensive, then banks can turn to the discount window to obtain reserve balances. In this way, the rate on discount window loans helps put a ceiling on the private market rate for reserve balances. As this interest rate, known as the federal funds rate, has been an important part of the setting of monetary policy, being able to promote stable conditions in the federal funds market better enables the Federal Reserve to implement monetary policy. The discount window is thus a critical tool that complements the Fed's other monetary policy tools.

For the discount window to succeed as a mechanism for delivering liquidity to banks, banks must be willing to borrow funds via the discount window as a source of backup, short-term liquidity. For decades, banks have demonstrated some reluctance to use the discount window in this manner out of concern that the act of borrowing might send a negative signal about their financial conditions to their counterparties, their competitors, their regulators, and the public. Such dynamics are referred to as the "stigma" associated with the use of the discount window. At various times, the Federal Reserve has made adjustments to discount window operating procedures in an effort to reduce stigma, but stigma likely persists today.

The presence of stigma poses a challenge for the Federal Reserve in responding to episodes of financial stress, as it impairs the ability of the discount window to serve effectively as a backup source of liquidity. For example, in August 2007, banks were extremely reluctant to turn to the discount window, which led to a great degree of caution in managing their liquidity and a disruption in the interbank market as a means to distribute liquidity. As concerns about bank conditions increased over the course of the financial crisis, the problems associated with stigma may have intensified. This likely resulted in significantly more stress in the interbank funding markets and tighter financial conditions than might have existed otherwise, in addition to more financial contagion.3

Despite the difficulties arising from stigma, the discount window has been and remains an important tool for responding to financial sector disruptions. For example, the Federal Reserve provided significant funding to the financial sector through the discount window to ensure continued market functioning following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack. In addition, during the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the discount window was used extensively despite the stigma associated with its use and helped prevent a financial market collapse. Given the value of the discount window as a liquidity backstop, regulators have issued guidance pointing to the discount window as an appropriate source of backup funding and many banks take steps to maintain their capability to borrow should the need arise.

Many of the changes and innovations to the administration of the discount window over the past few decades have been the results of efforts to address stigma. In this note, we discuss several topics related to stigma in depth and describe how concerns about stigma have influenced changes in Federal Reserve discount window policies. In the course of this discussion, we review:

- The basic mechanics of borrowing from the discount window,

- The reasons for stigma and the problems it creates,

- The recent history of the discount window, including redesign of its facilities in 2003 and the use of the discount window during the 2007-2009 financial crisis,

- Stigma and the discount window today.

Discount window basics

The discount window provides loans from the Federal Reserve to depository institutions: commercial banks, thrifts, and credit unions that maintain reservable liabilities (i.e. liabilities subject to reserve requirements). U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks that maintain reservable liabilities are also able to borrow under the same general conditions as domestic banks. The twelve Reserve Banks extend the loans made in their districts. Loans are short-term, typically overnight. All discount window loans must be fully collateralized to the satisfaction of the lending Reserve Bank, with an appropriate haircut applied to the collateral. In other words, the value of the collateral must exceed the value of the loan.

Reasons why stigma occurs

The presence of stigma depends on the combination of at least two factors. The first factor is that banks bear some cost from accessing the discount window such that borrowing from the window is less attractive than would typically be the case for accessing funds from private markets. This cost could be a non-pecuniary cost, such as the administrative burden associated with borrowing, but borrowing from the discount window could be less attractive than borrowing from the market simply because the discount window is more expensive. The second factor that is necessary to give rise to stigma is that market participants have imperfect information. Since banks are relatively opaque and publicly available information about their financial health is released with a lag, it can be difficult for financial market participants to determine in real time whether a bank is in poor financial condition. As a result, financial market participants look for signals about any given bank's condition, one of which can be whether a bank borrows from an expensive or burdensome source of funding. The discount window is then stigmatized to the extent that banks are reluctant to borrow because of concerns that such an action might be interpreted by others as a signal of trouble to the extent that the bank's borrowing from the discount window can be known.4

Stigma has the potential to be self-reinforcing. If banks are concerned that borrowing from the discount window could be viewed as a signal of trouble, those institutions may try to avoid the discount window as much as possible. This could potentially lead to a situation in which the only banks borrowing from the window would be those that could not avoid it, because they face severe difficulties in accessing market funding. This adverse selection dynamic could reinforce the view that borrowing from the discount window is a signal of severe difficulties.5

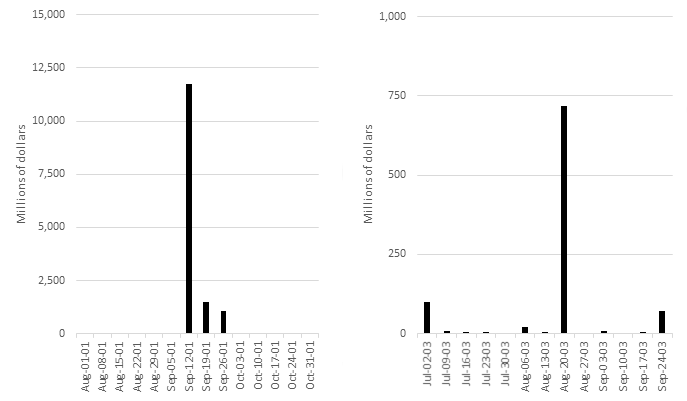

In contrast, banks may be able to borrow from the discount window without fearing stigma if the cause of borrowing is well known and obviously not a signal of poor condition. For example, banks have widely borrowed from the discount window following market disruptions clearly beyond their control. Figure 1 shows discount window loans surging after the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001, which disrupted normal payment system operations.6 The figure also shows an increase in discount window loans after the Northeast electrical black out in August 2003, which disrupted the federal funds market.7

Figure 1: Discount window borrowing around the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack and the August 14, 2003 east coast blackout

Left: Figure 1A. Borrowing around September 11, 2001. Right: Figure 1B. Borrowing around August 14, 2003

Note: Figures show average daily discount window borrowing for the weeks ending on the dates shown.

Source: Factors Affecting Reserve Balances, Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.4.1 (August 1, 2001 – October 31, 2001 and July 2, 2003 – September 24, 2003).

Problems associated with stigma

Stigma impairs the ability of the discount window to serve as a crisis response tool and as a tool to help the Federal Reserve implement monetary policy.

During stress events, stigma may become even worse than in normal times. When investors are particularly concerned about difficulties at banks, they may pay extra attention to any signals of potential weakness. Investors in bank debt, including depositors, may also react more strongly to such signals in times of stress, particularly if they are not covered by deposit insurance. Thus, to the extent that a discount window loan is perceived as a negative signal, banks may be concerned that this signal could be taken more seriously by counterparties during periods of stress and may make extra efforts to avoid the discount window. This may impair the functioning of short-term funding markets, exacerbating the problems, and may lead to tighter financial conditions. Such a situation occurred following the 1987 stock market crash, where banks sought to hold larger amounts of reserve balances than before but were even more reluctant to borrow from the discount window.8 These concerns were even more prominent during the 2007-2009 financial crisis, as discussed below.

Stigma also limits the usefulness of the discount window as a tool to facilitate the implementation of monetary policy. When the Federal Reserve adjusts monetary policy it typically does so by targeting a short-term interest rate. At times, normal business activities, such as settlement of Treasury auctions, can result in notable fluctuations in liquidity demand which in turn cause fluctuations in short-term interest rates. Clouse (1994) discusses how banks' reluctance to borrow from the discount window during the early 1990s intensified upward pressure on the federal funds rate on days of high demand for reserve balances.9 If there is no stigma associated with the use of the discount window, then the discount window can serve as a ceiling on short-term rates as banks would generally not pay more to borrow in the market than it costs to borrow from the Federal Reserve. If the discount window effectively limits fluctuations, the Federal Reserve has better control over short-term rates and liquidity conditions. When the discount window suffers from stigma, banks are reluctant to borrow from the Federal Reserve even when doing so would be cheaper than borrowing in the market. This makes implementation of policy more difficult as short-term market rates can rise more sharply and financial conditions might be tighter than would otherwise be the case.

Redesign of discount window facilities in 2003

Prior to 2003, some aspects of the discount window's design and administration likely had been contributing to stigma. Starting in the late 1960s, the discount window interest rate had been set below the target federal funds rate. This created a financial incentive for banks to engage in arbitrage by borrowing from the discount window and lending in other money markets. In order to limit such arbitrage, the Federal Reserve required institutions to attempt to obtain funding from their usual sources before accessing the window. This requirement forced banks that were short of funds to reveal that need to market participants. In addition, discount window borrowing was (and still is) disclosed at both the aggregate level and Federal Reserve district level. As a result, if market participants saw increases in borrowing they might be able to infer which institutions had been unable to obtain funds in the market, especially if a large amount was borrowed in a district with relatively few large banks. Thus this administrative requirement could have increased the likelihood that market participants could guess the identity of discount window borrowers.10

Partly in response to these concerns, the Federal Reserve redesigned the discount window in 2003 and made associated changes in its operating procedures. It raised the discount rate so that it was above the federal funds rate which removed the incentive for arbitrage and the need for administrative monitoring to prevent arbitrage. This reform also brought Federal Reserve policy in line with other central banks that use an above-market rate as a means of setting a ceiling on the overnight federal funds rate. The redesign involved the establishment of two new discount window facilities: the primary credit facility and the secondary credit facility, replacing two previously existing facilities.11

The primary credit facility is structured to create the opportunity for institutions to borrow without sending a signal of poor condition. Lending through the facility is short-term, typically overnight. The facility is available only to generally sound depository institutions, such as those receiving high supervisory ratings, which is intended to mitigate the extent to which market participants should perceive borrowing from the facility as a sign of poor condition.12 Though the primary credit facility has an above-market rate, currently set at 50 basis points above the upper limit of the Federal Open Market Committee's target range for the federal funds rate, it has less administrative burden than was previously the case. For example, the primary credit facility does not require institutions to exhaust reasonably available alternative sources of funds before approaching the discount window, and it imposes no restriction on the use of funds. The ability to access the discount window without first approaching the market also reduces the ability of other market participants to identify the discount window borrower. The removal of restrictions on the use of funds simplified the application procedure and reduced the administrative costs associated with the loan request.

The secondary credit facility is designed to meet backup liquidity needs from depository institutions that are not eligible for primary credit. Secondary credit is also extended on a short-term basis, typically overnight, at a rate that is above the primary credit rate. Loans provided through this facility are available to meet backup liquidity needs when "in the judgment of the Reserve Bank, such a credit extension would be consistent with a timely return to a reliance on market funding sources (Federal Reserve, Regulation A §201.4(b)." Unlike primary credit, there are restrictions on the uses of funds obtained through secondary credit, and use of this facility entails a higher level of Reserve Bank administration and oversight. Having separate facilities for banks based on their condition—specifically, having another facility specifically designated for banks not in generally sound condition--was intended to reduce the stigma associated with the use of primary credit.

The establishment of these facilities in 2003 also included public outreach. In 2002, an article in the Federal Reserve Bulletin (Madigan and Nelson 2002) described the purpose of the proposed changes.13 In 2003, federal banking regulators, including the Federal Reserve, issued guidance for depository institutions in their use of the new discount window facilities. The guidance encouraged these institutions to consider the potential role that the discount window might have in managing their liquidity, and consider the appropriateness of incorporating the discount window in their liquidity management planning. In addition, the guidance stated that supervisors and examiners should view the occasional use of primary credit as appropriate and unexceptional. 14

The redesigned discount window was in place for only a handful of years before the onset of the 2007-2009 financial crisis. During the years between the switch to the new facilities and the crisis, the pattern of borrowings from the discount window provides some indication that banks were willing to borrow from the primary credit facility at times when market rates were relatively more expensive. Artuc and Demiralp (2010) looked for a change in the responsiveness of discount borrowing to spikes in the federal funds rate and found that after the change to primary credit, banks borrowed more from the discount window when the federal funds rate spiked than they had previously. This finding suggests that the redesign of the discount window was at least somewhat effective in reducing stigma and that, as a result, the discount window may have been more effective in placing a ceiling on short-term funding rates, aiding the implementation of monetary policy, and serving as a tool to provide liquidity when needed.

Nevertheless, some stigma likely remained after these reforms. Furfine (2003), for example, suggests that borrowing from the primary credit facility in 2003 was still lower than what would have been expected from cross-sectional dispersion in federal funds market rates.

Stigma and alternative discount window tools during the recent financial crisis

The 2007-2009 financial crisis is an example of the sort of intense demand for liquidity which the Federal Reserve was founded to address. Indeed it was in many ways a classic scenario in which central bank liquidity provision can help address a serious financial disturbance in which there are increased demands for liquidity, a decline in the willingness of banks to provide liquidity support to others, and a decrease in the functioning of short-term funding markets through which liquidity is distributed throughout the banking system and the rest of the financial system.

As the crisis intensified over the course of 2007 and 2008, demand for liquidity, and short-term interest rates both, surged. In response, the Federal Reserve made temporary changes to the primary credit facility, narrowing the spread between the primary credit rate the FOMC's target federal funds rate, from 100 basis points to 25 basis points, and increasing the maximum term of lending to up to 90 days. These changes were designed to promote the restoration of orderly conditions in financial market by providing banks with greater assurance about the cost and availability of funding.

However, stigma intensified as well, mitigating the effectiveness of these changes to the primary credit facility. Banks became more reluctant to turn to the window, even as overnight rates rose, in part because the potential negative signal could be taken more seriously by counterparties given the exacerbated market stresses present at the time. Because of the higher risk that troubled institutions could fail, market participants were looking more carefully for signals of weakness and reacted more strongly to those signals. Consequently, banks took extra care to avoid actions that might be perceived as sending a negative signal, and stigma associated with the discount window appears to have increased. Although borrowers of primary credit were required to be of generally sound condition in order to use the facility, market participants appear to have found this determination to be less convincing given the uncertainty in a fast-moving crisis.

A sign of stigma during the crisis was the willingness of banks to borrow funds at rates that exceeded the rate charged at the discount window, thus signifying their desire to avoid the window even when funding markets made funding costly to obtain. Klee (2011) found that the volume of brokered federal funds transactions at rates above the primary credit rate increased during the first stages of the crisis.15

To address the severe strains in funding markets that persisted in part because stigma made banks less willing to use the primary credit facility, the Federal Reserve introduced a new lending facility for banks, the Term Auction Facility (TAF), in 2007. The TAF was designed as an alternative source of liquidity for banks that typically would have turned to the primary credit facility.16 The TAF had several features designed to minimize stigma. The TAF featured delayed settlement, with funds generally being delivered two days after the auction, so use of the facility would not signal that the bank had an immediate funding need. The rate at which institutions could borrow at the TAF was determined by auction, so that it was market-determined. TAF auctions were also announced in advance with the amount of funding pre-determined, which made it even less likely that market participants would infer that borrowing institutions had an immediate need for funds. The large number of participants in the TAF auctions also helped provide anonymity to individual institutions. Finally, there was also a slightly more stringent soundness requirement, as borrowers were expected to remain in sound condition over the slightly longer term of the advance.

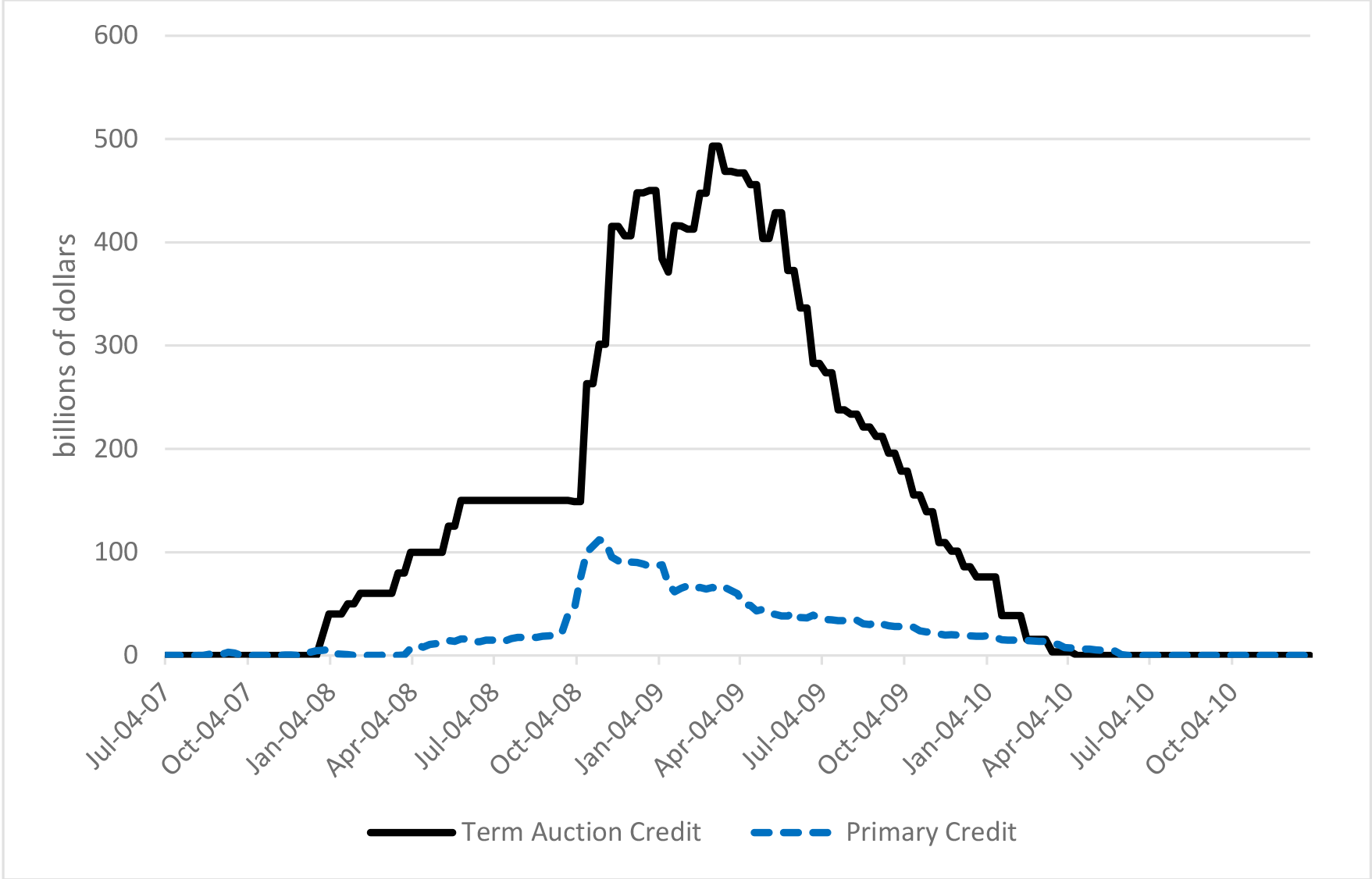

The TAF proved to be a useful tool during the crisis. Consistent with its design, concerns about stigma appeared to be less of an issue for the TAF than the discount window; far more credit was extended using the TAF than through the primary credit facility (Figure 2). Moreover, the TAF appears to have been successful in alleviating disruptive financial market stress. McAndrews, Sarkar, and Wang (2017) find that the TAF helped relieve strained conditions in interbank markets during the crisis while Berger, Black, Bouwman, and Dlugosz (2017) find that TAF loans helped support bank lending.17

Figure 2: Federal Reserve lending to banks through the Term Auction Facility and the Primary Credit Facility during the financial crisis

Note: For Term Auction Credit the figure shows the amount of credit outstanding as the end of the week. For Primary Credit, the figure shows the average of daily credit outstanding for the week ending on the same dates as shown for the Term Auction Credit.

Source: Factors Affecting Reserve Balances, Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.4.1 (July 4, 2007 - December 29, 2010).

However, funds available through TAF were not a complete substitute for funds from the primary or secondary credit facilities if an institution needed funds more quickly or in an amount that exceeded the maximum bid amount allowed at a TAF auction. Furthermore, the existence of the TAF may have further stigmatized primary credit, which became a fallback for nominally sound depository institutions that were judged too risky for the longer term credit available through the TAF.

Stigma and the discount window today

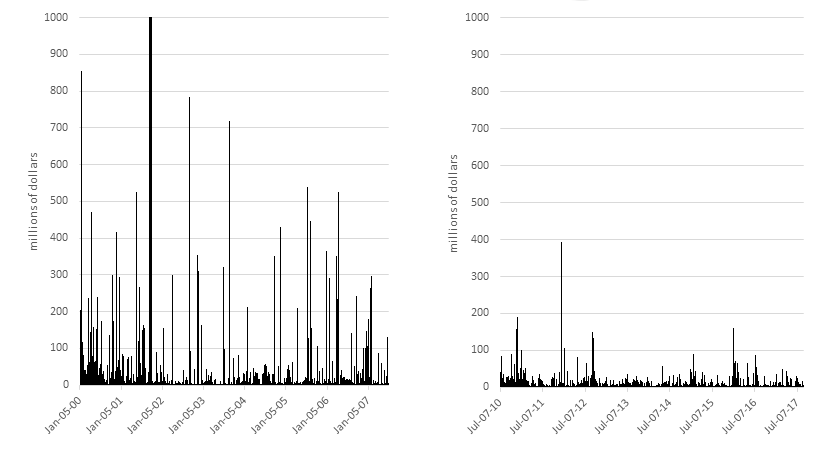

Since the crisis, discount window use has been low. As shown in Figure 3, the average weekly borrowing since mid-2010 has been low, even relative to what it was in the years prior to the crisis. Depository institutions have likely had little need to borrow given the abundance of reserve balances in the financial system as the Federal Reserve System's balance sheet has expanded significantly. In addition, episodes of financial stringency have been limited. Thus it is not clear the extent to which the discount window continues to suffer from stigma. However it is very likely that stigma remains a problem. Indeed, Federal Reserve Board Vice Chairman Fischer has recently stated that he suspects stigma is even higher in the post-crisis period, given the public's incorrect association of the discount window with "bailouts."18

Left: Figure 3A. Borrowing pre-crisis. Right: Figure 3B. Borrowing post-crisis.

Note: Figures show average daily discount window borrowing for the weeks ending on the dates shown. Average weekly borrowing exceeded $1 billion following the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001 and during the financial crisis.

Source: Factors Affecting Reserve Balances, Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.4.1 (January 5, 2000 – June 27, 2007 and July 7, 2010 – August 30, 2017).

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act has also introduced new disclosure requirements for the discount window intended to promote more transparency and accountability to the public in the administration and use of the discount window. The Dodd-Frank Act requires the Federal Reserve to publish information on individual discount window borrowers and transactions after approximately two years. Before the passage of this Act, the Federal Reserve had published information on discount window borrowing only on an aggregated basis (at the district and system level), though with only a short time lag. The provision in the Dodd-Frank Act regarding disclosure provides for a two-year lag before individual borrowers' identities are revealed. Congress intended that this two-year lag would mitigate the extent to which the disclosures could exacerbate stigma since market participants and analysts would theoretically be unlikely to significantly alter their view of a counterparty based on two-year old information. Nevertheless, banks may choose to avoid the discount window even with a lag in disclosures if they would prefer to avoid the burden of explaining such an action even two years later.

Despite the continued presence of stigma, the discount window remains a valuable liquidity backstop. While it is important that the banks have robust liquidity management policies, it is not economically efficient for the banks to maintain sufficient liquidity on-hand to meet any possible situation.19 Instead, the Federal Reserve in general was intended should provide additional liquidity to the banking system during such episodes and primary credit in particular was designed to help the Federal Reserve do so.

Given the value of the discount window in preventing small disruptions to financial markets from becoming major disruptions, readiness to use the discount window as a backup source of liquidity remains important despite the stigma associated with its use. Many banks do include the use of the discount window in their contingency plans, maintaining collateral at the Federal Reserve that could be used to secure loans and conducting periodic test borrowings.20 Indeed, even though the weekly average amount of borrowing has remained below the levels observe prior to the financial crisis, the number of borrowers in a typical week has been notably higher. Bank regulators have also issued guidance noting that doing so is entirely consistent with appropriate contingency planning and that "[i]t is a long-established sound practice for institutions to periodically test all sources of contingency funding. Accordingly, if an institution incorporates primary credit in its contingency plans, management should occasionally test the institution's ability to borrow at the discount window. The goal of such testing is to ensure that there are no unexpected impediments or complications in the case that such contingency lines need to be utilized."21

1. We thank Sophia Allison, James Clouse, Erin Ferris, Lyle Kumasaka, Laura Lipscomb, Marco Machiavelli, Brian Madigan, Sean Savage, Peter Stoffelen, and Mary-Frances Styczynski for valuable comments. Return to text

2. For an example of idiosyncratic factors, in 1985 the Bank of New York suffered a computer failure associated with its activities settling trades involving Treasury securities in the middle of a business day. It borrowed from the discount window an amount that, at the time, was a record. See Ennis and Price (2015): "Discount Window Lending: Policy Trade-offs and the 1985 BoNY Computer Failure," https://www.richmondfed.org/~/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/economic_brief/2015/pdf/eb_15-05.pdf Return to text

3. See Donald Kohn (2010), "The Federal Reserve's Policy Actions during the Financial Crisis and Lessons for the Future," speech at the Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada May 13 https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/kohn20100513a.htm and Brian Madigan (2009). "Bagehot's Dictum in Practice: Formulating and Implementing Policies to Combat the Financial Crisis," speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City's annual Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/madigan20090821a.htm. Return to text

4. Madigan, Brian and William Nelson (2002). "Proposed Revision to the Federal Reserve's Discount Window Lending Program," Federal Reserve Bulletin, July, pp. 313-319. https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2002/0702lead.pdf Return to text

5. Clouse, James (1994). "Recent Developments in Discount Window Policy," Federal Reserve Bulletin, November, pp. 965-977. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/1194lead.pdf Return to text

6. Ferguson, Roger (2002), "Implications of 9/11 for the Financial Services Sector," speech at the Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, Chicago, May 9. https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2002/20020509/default.htm Return to text

7. Olson, Mark (2003), "Power outages and the financial system," testimony before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives. https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/testimony/2003/20031020/ Return to text

8. Banks wanted to hold higher balances, but not borrow them from the Federal Reserve. Instead, they competed for these funds in the market and drove up market rates. Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "Monetary Policy and Open Market Operations during 1987," https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/quarterly_review/1988v13/v13n1article4.pdf Return to text

9. Clouse, James (1994). "Recent Developments in Discount Window Policy," Federal Reserve Bulletin, November, pp. 965-977. Return to text

10. Madigan, Brian and William Nelson (2002). "Proposed Revision to the Federal Reserve's Discount Window Lending Program," Federal Reserve Bulletin, July, pp. 313-319. Return to text

11. A third facility, seasonal credit was left unchanged by the redesign. The seasonal credit program assists small depository institutions in managing significant seasonal swings in their loans and deposits. Eligible institutions are usually located in agricultural or tourist areas. Return to text

12. The high supervisory ratings are based on a combination of capital adequacy category and supervisory (CAMELS) rating. See https://www.frbdiscountwindow.org/en/Pages/General-Information/Primary-and-Secondary-Lending-Programs.aspx#elig. The reserve banks retain some discretion to impose additional restrictions on borrowers if they have particular concerns. Return to text

13. Madigan, Brian and William Nelson (2002). "Proposed Revision to the Federal Reserve's Discount Window Lending Program," Federal Reserve Bulletin, July, pp. 313-319. Return to text

14. Interagency Advisory on The Use of the Federal Reserve's Primary Credit Program in Effective Liquidity Management. https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/srletters/2003/SR0315a1.pdf. Return to text

15. Klee, Elizabeth. (2011) "The First Line of Defense: The Discount Window During the Early States of the Financial Crisis." Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2011-23. See also the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2015) "Discount Window, Specialized Course in U.S. Monetary Policy Implementation." https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/banking/international/09.28.2015-discount%20window-4.00pm.pdf Return to text

16. See Brian Madigan (2009). "Bagehot's Dictum in Practice: Formulating and Implementing Policies to Combat the Financial Crisis," speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City's annual Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/madigan20090821a.htm. The Federal Reserve also introduced facilities for non-banks given the extent to which market functioning was disrupted. We do not discuss those facilities here, as those facilities are quite different and the concerns regarding stigma are different. Return to text

17. James McAndrews, Asani Sarkar, and Zhenyu Wang (2017). "The effect of the term auction facility on the London interbank offered rate," Journal of Banking and Finance. Allen Berger, Lamont Black, Christa Bouwman, and Jennifer Dlugosz (2017), "The Federal Reserve's Discount Window and TAF Programs: "Pushing on a String?," Journal of Financial Intermediation. Return to text

18. Stanley Fischer (2016), "The Lender of Last Resort Function in the United States," speech at "The Lender of Last Resort: An International Perspective," a conference sponsored by the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation, Washington, D.C. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/fischer20160210a.htm Return to text

19. The value of having a lender of last resort so that banks do not have to maintain sufficient liquidity to meet all contingencies appears in Walther Bagehot (1873), Lombard Street, (London: Henry S. King & Co.) and Paul Warburg (1916), "The Reserve Problem and the Future of the Federal Reserve System," speech delivered before the convention of the American Bankers Association, Kansas City, Missouri, September 29, 1916. Return to text

20. It is difficult to know what constitutes a test borrowing, but it is likely that small value transactions are test borrowings. In the second quarter of 2015, the most recent quarter for which the Federal Reserve has released information publicly on discount window borrowing, there were 1,031 discount window loans extended. More than one-third of these loans were for amounts of $10,000 or less. Return to text

21. Interagency Advisory on The Use of the Federal Reserve's Primary Credit Program in Effective Liquidity Management, page 4. Return to text

Carlson, Mark, and Jonathan D. Rose (2017). "Stigma and the discount window," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 19, 2017, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2108.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.