FEDS Notes

September 08, 2023

Understanding Workers' Financial Wellbeing in States with Right-to-Work Laws

Kabir Dasgupta1 and Zofsha Merchant2

Introduction

As public interest in labor unions has increased in recent months, along with an increase in union representation petitions, it is valuable to understand the economic implications of labor unions.3 Previous empirical studies on the effects of labor unions and collective bargaining processes have focused on several economic outcomes ranging from workers' pay and productivity to firms' profitability, investments, and overall economic performance.4 More broadly, it is important to understand how policies that affect unionization rates also affect individual workers' financial outcomes and wellbeing. In this note, we focus on one of the key legislative interventions that drive some of the differences in union density across US states, namely Right-to-Work (RTW) laws. Specifically, we extend the existing literature on RTW laws by focusing on the effects on financial wellbeing of individuals in states that implement the legislation.

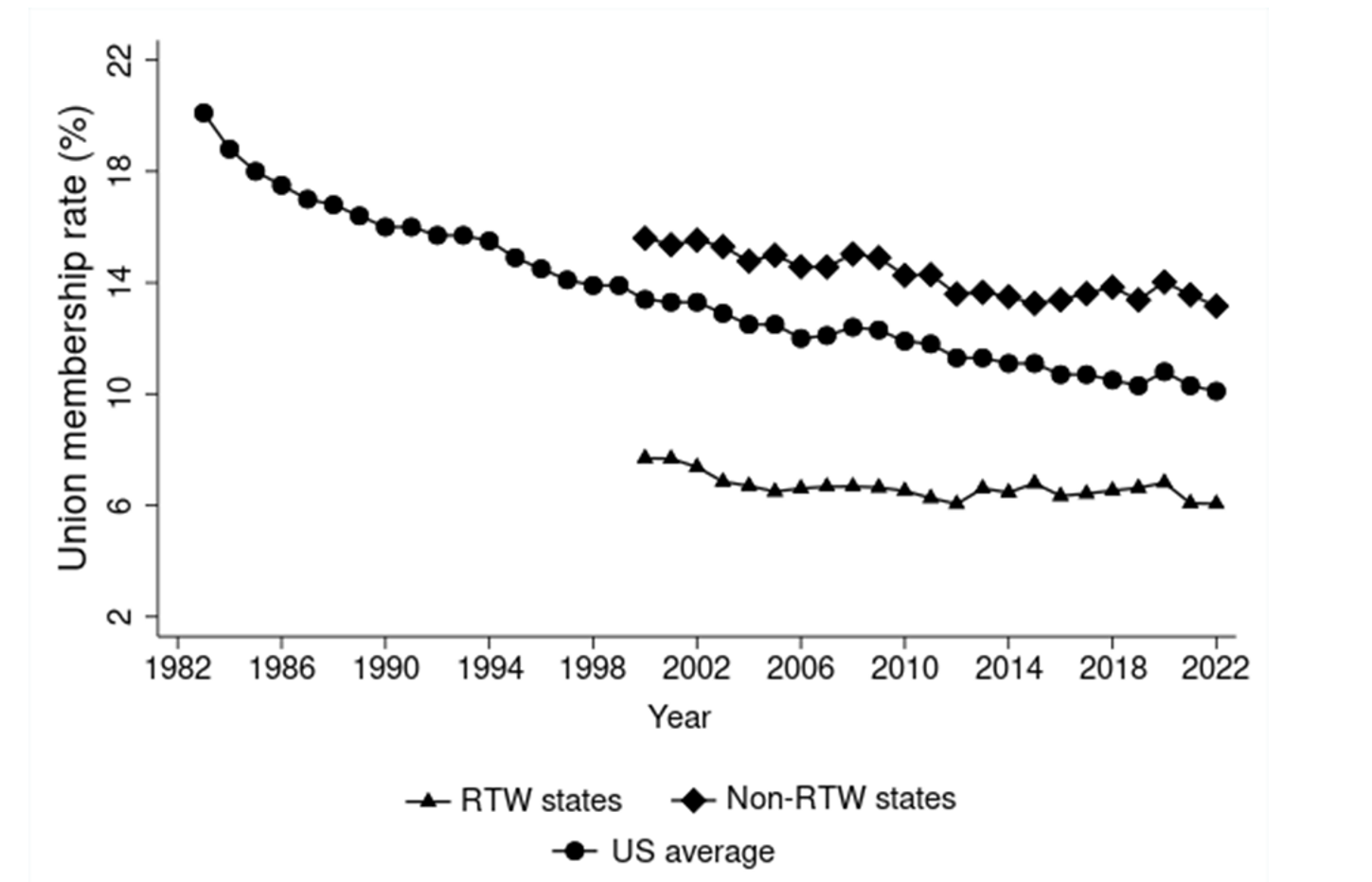

In general, RTW laws provide workers with the option to opt out of union expenses when working at a unionized establishment. For those who opt out of union membership where RTW laws are in place, workers can avoid the cost of paying union dues or representation fees to maintain their employment status. However, they can still receive the non-excludable benefits of the union's collective bargaining.5 The share of unionized workers is typically lower in states with RTW laws than in states where RTW laws have not been enacted.6 As shown in Figure 1, the union membership rate in RTW states stood at 6 percent in 2022—less than half of the 13-percent share observed in states without a RTW regulation.

Note: Staff analysis using BLS data on union membership in all industries.

Prior research has shown that union membership contributes to differences in wages and other employment-related outcomes among workers.7 Therefore, the primary focus of prior RTW literature has been on unionization and various labor market outcomes including employment and earnings.8 Since changes in labor market outcomes could directly affect individuals' financial wellbeing, our note extends the focus of the existing research on RTW laws to the previously unexplored outcomes related to people's financial wellbeing.

First, we exploit recent state-level policy changes in an event study design to present labor market trends before and after the passage of RTW legislation. We consolidate results from the prior literature by considering measures of employment status, labor earnings, union membership level, and job openings using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). Next, we utilize the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) to present summary statistics of job-related and financial characteristics for unionized workers and non-unionized workers, classified by states with and without RTW legislation. Finally, we employ a difference-in-differences framework to explore the link between the passage of a RTW legislation and workers' financial characteristics such as access to a credit card, emergency preparedness, and self-reported indicator of personal financial conditions.

Right-to-Work Laws – Historical Background and Existing Evidence

The passage of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) in 1935 guaranteed workers the right to unionize and collectively bargain over wages, work hours, and other employment benefits. The 1935 legislation also allowed for provisions under which the collective bargaining contracts between firms and labor organizations could require all workers covered under the union to pay union dues. Such contracts are called union security agreements.9 However, just over a decade later in 1947, the NLRA was amended by the Taft-Hartley Act, which opened the door for states to supersede the provisions of the NLRA, allowing them to prohibit union security agreements by enacting RTW laws. Specifically, the RTW laws enabled states to remove the requirement for workers to join a labor union and pay the required union representation costs as a condition of their employment.10 As a result, under RTW laws, while workers could refuse to join a labor union, they could still enjoy the wage and non-wage benefits from labor unions' collective bargaining. However, achieving workers' benefits can be costly and are typically financed by union dues accrued from union members.11 As such, it has been suggested that the implementation of RTW laws can encourage free-ridership while weakening the strength of organized labor.12

The negative relationship between the passage of RTW laws and the extent of unionization has been well-documented in the relevant literature. Some earlier studies suggest that the lower levels of union membership observed in RTW states might be driven by pre-existing preferences towards unions and region-specific differences in public attitudes rather than the passage of RTW laws themselves.13 Overall, these studies indicate that it is important to account for the unobserved effects of prevalent attitudes and simultaneity biases when causally identifying the effects of RTW laws on unionization. In other words, the size of the unionized work force could contribute to the passage of RTW laws rather than the other way around. However, even after controlling for some of the unobserved heterogeneities, Ellwood and Fine (1987) found evidence that passage of a RTW law is followed by a "strong short-run reduction in union organizing," resulting from a decrease in the number of certification elections and a reduction in the average number of workers in each new bargaining unit. As such, Ellwood and Fine's results indicate that RTW laws have a negative impact on the "flow" into union membership, which eventually affects the "stock" of union membership in the long run. The adverse impact of the RTW laws on union density as well as union coverage has been later substantiated by several other studies.14

The role of RTW laws in curbing the strength of labor unions has prompted extensive academic and political discussions. Proponents of RTW laws argue that passage of such laws support business investments and long-term economic growth. These arguments find support in several studies that show states with "pro-business" RTW laws have seen a substantial growth in private sector employment, especially in manufacturing activity.15 Moreover, according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, from 1990 to 2011, states with RTW laws saw a much faster growth in overall employment and nominal income levels than non-RTW states.16

Conversely, critics of RTW laws assert that such regulations considerably undermine the wage and non-wage benefits that organized unions could achieve for workers. Corroborating this viewpoint, various studies have documented that the passage of RTW laws is followed by a statistically significant decline in wage income of employees.17 Additional research has also found that rates of employer-sponsored pensions and health insurance are lower in states with RTW laws.18

It is worth noting that from a research standpoint, the evidence regarding the effects of RTW laws are mixed and even conflicting at times. For instance, while numerous papers find a negative impact of RTW laws on wage levels, some studies offer alternative evidence.19 As an example, Eren and Ozbeklik's (2016) analysis on Oklahoma's passage of RTW regulation in 2001 finds that the regulation did not have any meaningful impact on private sector employment or wages. Additionally, focusing on four states that implemented RTW laws between the 1960s and 2000s, Jordan et al. (2020) detect no relevant impact of RTW laws on income inequality. On the other hand, a study by Reed (2003) documents a positive effect of RTW laws on wage income. As Moore (1998) infers, the differences in the findings in the RTW literature could be due to the differences in the methodological approaches adopted to identify the regulation's effects.

Nonetheless, given the large body of empirical evidence on the discernible effects of RTW laws on employment and wage levels, it is reasonable to hypothesize that RTW laws could be linked to individuals' financial and subjective wellbeing.20 Though there exists limited evidence on the impact of the RTW legislation on individuals' life satisfaction and economic sentiment, to our knowledge, no other studies have looked into individuals' financial wellbeing.

Right-to-Work Laws and Labor Market Effects

To understand the effects of recently implemented RTW laws, we first focus on the commonly studied labor market outcomes. We use individual-level annual surveys from the CPS Annual Social and Economic Supplement for the period 2000-2020 to study the dynamic trends in employment propensity and labor market earnings before and after a RTW law is introduced. During the period under evaluation, there were six states that enacted RTW laws. Those states include Oklahoma (2001), Indiana (2012), Michigan (2012), Wisconsin (2015), West Virginia (2016), and Kentucky (2017).

We track the labor market indicators for a period ranging from six years before and six years after a RTW law was enacted. We exclude from our analysis all states that had already enacted RTW legislation prior to 2000 so that we can compare the above-mentioned six states with those that have never enacted a RTW law. Moreover, we consider a sample of prime-aged individuals (25-64) who are in the labor force.21 For additional insights, we also look at the aggregated measures of union membership rates and job opening rates in our event analysis.22

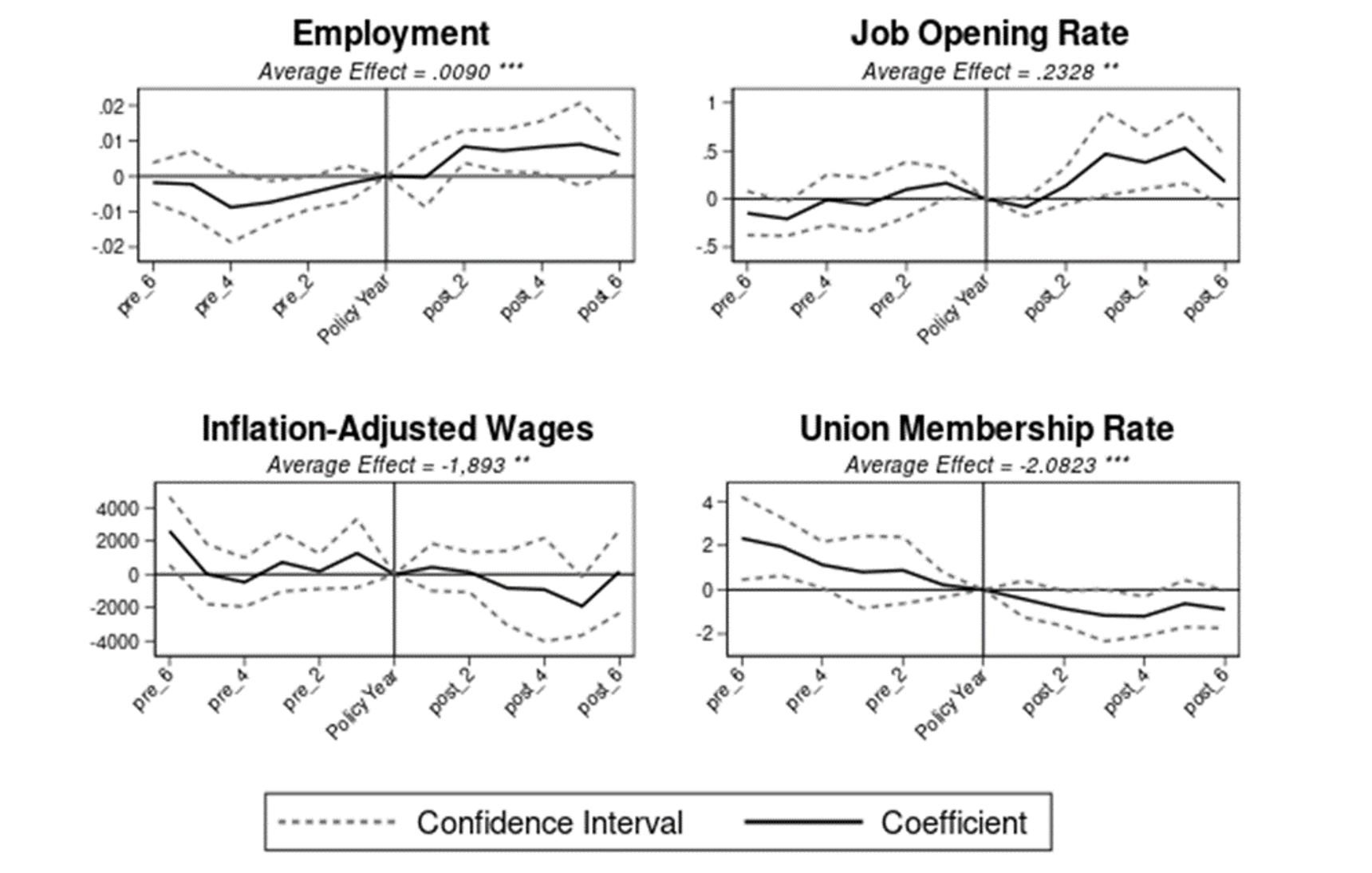

In Figure 2, we graphically present our findings which provide suggestive evidence into some of the insights already highlighted in the existing RTW literature. First, on average, for prime-aged individuals who are in the labor force, we see a slight but statistically significant uptick in the probability of being employed in states that enact RTW laws. Quantitatively, our model indicates that the enactment of a RTW law is associated with an increase in the probability of being employed of approximately 1 percentage point. This positive change in the employment propensity could be driven by the pro-business sentiment typically associated with RTW jurisdictions. Consistent with this argument, we see a small average increase in the job opening rate (of 0.2 percentage points) during the years following the enactment of a RTW law.

However, despite the increase in employment, we also find that the passage of a RTW law is followed by a statistically significant decline in annual wages by almost $1,900. This decline amounts to approximately 4 percent of the baseline mean annual wage earnings of $46,267. To avoid potential sample selection issues, these declines are not just for individuals who are working, but all prime-aged adults. One of the underlying reasons behind the decrease in annual earnings could be a reduction in the strength of labor unions in states that pass RTW laws. Along that line of reasoning, we also find that in states that enact RTW laws, the overall union membership rate declines by an average of 2 percentage points during post-implementation years.

The point estimates of the average effect obtained from a two-way fixed effects specification that exploits variation in the enactment of state-level legislation at different time points appears to be consistent with the aggregated average treatment effects estimated using alternative specifications developed in the recent empirical literature for staggered policy interventions. 23 Additionally, in most cases, the recent RTW legislation enacted in the six states does not apply to federal employees or to the employees of the airline or railways sectors. Our results on employment and wage earnings do not vary if we drop individuals in the labor force who work in those sectors.

Notes: In the above figure, the employment-related outcome is a binary indicator that equals 1 if an individual in the labor force is employed, and 0 if unemployed. The analysis on employment and inflation adjusted wages is for prime-aged adults (between 25-64) only. For labor market earnings, we consider a continuous measure of annual wage deflated to 2010 dollars using the consumer price index (CPI-U-RS). The measures of job opening rate and union membership rate are expressed in percent terms. We drop the year of passage from our analysis as the reference category. In all regressions, we control for various individual-level characteristics such as age, race, ethnicity, sex, marital status, and educational attainment and for the political affiliation of the state's governor as a proxy for state-level characteristics. We also control for state- and year-fixed effects.

As highlighted in the earlier literature, the graphs in Figure 2 also demonstrate the potential challenges in deriving causal inferences regarding the effects of RTW legislation. To explain, the line graph representing the regression coefficients estimated from the event analysis of union membership rate appears to be on a trajectory of decline over time leading up to the passage of a RTW legislation. As such, we may not rule out the possibility of any anticipatory effects during the periods leading up to the enactment of a RTW law. When we consider employment propensity and job opening rate, we also find some evidence of significant differences between states that enact RTW legislation and non-RTW states during the years preceding the passage of a RTW law. However, the trends are not as apparent as that of the union membership rate.

Right-Work-Laws, Union Membership, and Financial Wellbeing

In this section, we use data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) to better understand whether introduction of a RTW legislation is associated with any change in individuals' financial wellbeing. We first use the SHED to compare employment-related outcomes and financial conditions between unionized and non-unionized workers. We utilize the last four annual surveys starting from October 2019 that document information on whether a worker is a member of a union or a similar employee association. We present the relevant summary statistics in Table 1, including information for union workers in highly unionized occupations and union workers in RTW states.

Table 1. Summary Statistics of Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) indicators

| Overall | Right to Work States (RTW) | Non-Right to Work States | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Union-membership rate | 0.137 | 0.083 | 0.186 |

| Membership rate in selected occupations✓ | 0.226 | 0.133 | 0.316 |

| Sample size | 21934 | 10520 | 11414 |

Employment and Financial Conditions of Employed Individuals

| SHED indicators | Overall sample | Union (a) |

Non-Union (b) |

RTW states (c) |

Non-RTW states (d) |

Union: Selected occupations✓ (e) |

P-value (a) – (b) |

P-value (c) – (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment-related- | ||||||||

| Asked for a raise/ promotion | 0.168 | 0.108 | 0.177 | 0.173 | 0.164 | 0.106 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Received a raise/ promotion | 0.501 | 0.523 | 0.498 | 0.505 | 0.498 | 0.523 | 0.01 | 0.35 |

| Apply for a new job | 0.266 | 0.198 | 0.277 | 0.276 | 0.257 | 0.182 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Voluntarily left job | 0.106 | 0.073 | 0.111 | 0.111 | 0.102 | 0.069 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Laid off or lost job | 0.078 | 0.067 | 0.08 | 0.073 | 0.083 | 0.058 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Insurance through employer/union | 0.800 | 0.921 | 0.781 | 0.779 | 0.818 | 0.921 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Financial outcomes- | ||||||||

| Has a credit card | 0.900 | 0.938 | 0.895 | 0.875 | 0.923 | 0.939 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Emergency funding with liquid assets | 0.472 | 0.511 | 0.466 | 0.475 | 0.469 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.36 |

| Financially managing OK/ comfortably | 0.787 | 0.818 | 0.783 | 0.773 | 0.801 | 0.808 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Credit score: Good/ Excellent | 0.808 | 0.834 | 0.805 | 0.778 | 0.836 | 0.823 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Minimum sample size | 18088 | 2529 | 15516 | 8608 | 9480 | 1460 | - | - |

| Maximum sample size | 22038 | 3001 | 18933 | 10566 | 11471 | 1716 | - | - |

Notes: ✓ Selected occupations include traditionally highly unionized occupations such as teaching and education, medical and health care services, protective services, and office and administrative support.

The above information is obtained from samples of employed workers aged 25-64 from SHED surveys 2019-2022. The P-values are obtained from two-sample tests of proportions that statistically test whether the proportions of the selected survey indicators in the sample of unionized workers in non-RTW states are equal to the corresponding proportions in the (a) sample of non-unionized workers in RTW states and (b) the sample of non-unionized workers in non-RTW states. The summary statistics for the unionized workers in the RTW states are not reported due to limited sample size. As the sample sizes for different indicators considered vary due to data availability, we report the minimum and the maximum sample size used in the analysis.

Consistent with the BLS data, the union membership rate in the SHED sample is lower in states with RTW regulations than in states without RTW laws. Additionally, occupation categories that tend to be highly unionized such as teaching and education, medical and health care services, protective services, and office and administrative support, were found to have higher rates of unionized workers in the SHED sample than the overall average.24

Focusing on employment-related outcomes in Table 1, non-unionized individuals are more likely to ask for a raise or a promotion themselves than unionized workers. However, unionized workers are more likely to receive a raise or a promotion. Together these findings possibly highlight the bargaining aspect of being a part of a labor union. We also find some evidence suggesting that unionized workers have greater job stability than non-unionized workers. To that end, Table 1 shows that relative to non-unionized workers, union workers are less likely to look for a new job, voluntarily quit their current job, or get laid off from their current job. Relative to non-union workers, a higher share of unionized workers receive health insurance through their employer or union. When comparing employment-related outcomes of workers in states with and without RTW laws, the descriptive evidence is mixed. Specifically, while RTW states appear to have a higher share of workers who apply for a new job or voluntarily leave their jobs, workers in non-RTW states are marginally more likely to be laid off from their jobs.

We next assess individuals' financial wellbeing by considering workers' access to a credit card, emergency preparedness, and self-reported evaluations of their financial conditions and credit scores. For emergency preparedness, we consider the share of individuals who report that they would use cash or cash-equivalent savings (checking or savings account) in case of a $400 emergency expense. In Table 1, we see unionized workers have greater financial wellbeing across all four of these indicators than their non-unionized counterparts. Employed workers in non-RTW states also seem to have higher average financial wellbeing than those in RTW states. The corresponding differences are statistically significant for all outcomes except for the indicator of whether a person would pay for small emergency expenses with liquid assets.

The differences observed between unionized and non-unionized workers in Table 1 motivate the relevance of studying the financial wellbeing implications of RTW laws. Additionally, the differences in the outcomes of workers in RTW and non-RTW states explain the importance of controlling for unobserved state-specific heterogeneities in regression analysis.

We use the SHED's annual surveys from 2013 through 2022 to analyze whether individuals' financial health varies with the enactment of a RTW law. 25 The period covered in our analysis allows us to capture variation in the enactment of a RTW law in only three states. Those states are Wisconsin (2015), West Virginia (2016), and Kentucky (2017).

In Table 2, we present our difference-in-differences estimates of the relationship between RTW laws and financial outcomes of prime-aged individuals in the labor force.26 Consistent with our earlier results, on average we find that the passage of a RTW law is followed by a 2-percentage point increase in the likelihood of being employed. This finding also holds when we analyze the likelihood of being employed using the CPS sample in SHED analysis period of 2013-2022. However, unlike our analysis using the CPS data, we are unable to test the wage effects using the SHED surveys due to the absence of the relevant data. 27

Table 2 – Estimating the Relationship Between RTW laws and Financial Outcomes of Individuals in Labor Force

| Employment (1) |

Financially managing OK/ comfortably (2) |

Access to credit card (3) |

Emergency expense: Liquid savings (4) |

Health insurance through firm/ union (5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample mean | 0.926 | 0.735 | 0.876 | 0.46 | 0.766 |

| Right-to-work law | 0.022*** | -0.004 | 0.002 | -0.016 | -0.015 |

| (0.005) | (0.015) | (0.009) | (0.025) | (0.020) | |

| Observations | 21,745 | 21,713 | 21,607 | 21,708 | 21,389 |

| Demographic information | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Marginal effects from Probit regressions are estimated using sample from SHED surveys 2013-2022. Robust standard errors are clustered on the states and are reported in parentheses. Individual-level controls include marital status, race, ethnicity, education level, family size, number of own children. Regression variables including outcomes and covariates are chosen by ensuring that the relevant data are available across most surveys. State-level control includes political affiliation of governor. All regressions additionally include State and survey year fixed effects. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

When we consider indicators of financial outcomes, the marginal effects in Table 2 reveal that the effect of recently implemented RTW laws on people's financial conditions is not statistically significant. This implies that despite the growth in employment seen in states with RTW laws, there's no discernible change in financial wellbeing for workers. It is possible that the decline in wages following the passage of RTW laws offset any benefits attained from increased employment in RTW states. Moreover, future research could also focus on the nature of employment gains observed in states that recently introduced a RTW legislation.

Finally, since RTW laws can affect individual outcomes through variations in union membership or union coverage, we turn our focus to employed workers only. However, the empirical caveat with this approach is that since workers' job stability can be endogenously determined by their association with a union, the sample of employed individuals could be a selective group and therefore could bias our analysis.

As an additional test prior to our final analysis, we use a subset of the SHED sample who are longitudinally tracked across multiple surveys to verify if previously employed individuals could experience any change in their employment status due to the introduction of a RTW law. Making use of the longitudinal aspect of the SHED data, we do not find any statistically meaningful variation in individual's employment following the adoption of a RTW regulation when we condition the sample on individuals' previous employment status.28

When looking at employed workers only, we see that RTW laws are negatively associated with individuals' likelihood of reporting they are financially "okay" or "living comfortably" rather than saying they are "just getting by" or "finding it very difficult to get by" (Table 3). Specifically, the passage of a RTW law is associated with an approximately 2-percentage point decline in the probability of doing okay or financially managing comfortably. The marginal effect is significant at the 10 percent level.

Table 3 – Estimating the Relationship Between RTW Laws and Employed Workers' Financial Outcomes

| Financially managing OK/ comfortably | Access to credit card | Emergency expense: Liquid savings | Health insurance through firm/ union | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Right-to-work law | -0.016* | -0.032** | 0.001 | 0.004 | -0.007 | -0.012 | -0.033 | -0.035 |

| (0.009) | (0.016) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.030) | (0.039) | (0.022) | (0.029) | |

| Selected occupations | -0.034*** | -0.017*** | 0.007 | -0.005 | ||||

| (0.010) | (0.005) | (0.012) | (0.007) | |||||

| RTW X Selected occupations | 0.042* | -0.004 | 0.013 | 0.006 | ||||

| (0.025) | (0.015) | (0.025) | (0.020) | |||||

| Observations | 20,113 | 20,113 | 20,014 | 20,014 | 20,107 | 20,107 | 19,815 | 19,815 |

| Demographic information | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Marginal effects from Probit regressions are estimated using sample from SHED surveys 2013-2022. Robust standard errors are clustered on the states and are reported in parentheses. Individual-level controls include marital status, race, ethnicity, education level, family size, number of own children. Regression variables including outcomes and covariates are chosen by ensuring that the relevant data are available across most surveys. State-level control includes political affiliation of governor. All regressions additionally include State and survey year fixed effects. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

In a separate specification, we interact the RTW law enactment with the indicator of being in an occupation that usually has a higher unionization rate than average. Our results suggest that workers in those selected occupations experience higher levels of financial wellbeing when their state introduces a RTW law. This is consistent with an increase in the differential between workers in less-unionized occupations and those who are in highly unionized occupations. These results also align with the academic discussion on union-non-union differentials in economic outcomes. For example, adoption of RTW laws could affect the union-non-union wage gap by lowering the possibility of union organization and providing firms with uncontested rights to set workers' wages (Farber 1984).

Conclusion

Our analysis extends the existing research on RTW laws by looking at individuals' financial wellbeing. Due to the limited number of survey periods in the SHED and absence of consistent data across surveys, our analysis is restricted in scope. We also note that the difference-in-differences analysis presented in this note at best presents associational evidence rather than a causal relationship. Nevertheless, it offers insights that can help inform work on this topic.

Our note focuses on comparing workers' financial outcomes in states that introduce RTW laws versus those that do not. Consistent with prior research, we find that following the passage of RTW laws, states experience an increase in job opening rates and employment levels but declines in wage and union membership rates. When expanding to workers' financial outcomes, our findings suggest that recently implemented state-level RTW laws are not associated with any significant variation in people's overall financial wellbeing. However, for employed workers, we find weak evidence of a negative association between the passage of RTW laws and self-reported indicator of financial conditions, although these effects are potentially concentrated in less-unionized occupations. These findings align with the empirically documented adverse relationship between the RTW laws and wage earnings. Overall, our study opens an important scope for future research to look into the causal mechanisms regarding broader financial implications of RTW laws.

References:

Austin, B., & Lilley, M. (2021). The Long-Run Effects of Right to Work Laws. (Working Paper). https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/matthew-lilley/files/long-run-effects-right-to-work.pdf

Blanchflower, D. G., & Bryson, A. (2020). Now unions increase job satisfaction and well-being (No. w27720). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Callaway, B., & Sant'Anna, P. H. (2021). Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 200-230

Card, D. (1996). The effect of unions on the structure of wages: A longitudinal analysis. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 957-979

Carroll, T. M. (1983). Right to work laws do matter. Southern Economic Journal, 494-509..

Chun, K. N. (2023). What do Right-to-Work Laws do to Unions? Evidence from Six Recently-Enacted RTW Laws. Journal of Labor Research, 1-51

Collins, B. (2014). Right to Work Laws: Legislative Background and Empirical Research. Congressional Research Service, no. R42575.

Davis, J. C., & Huston, J. H. (1995). Right-to-work laws and union density: New evidence from micro data. Journal of Labor Research, 16(2), 223-229

Eisenach, J. A. (2018). Right-to-Work Laws: The Economic Evidence. NERA Economic Consulting. https://www.nera.com/content/dam/nera/publications/2018/PUB_Right_to_Work_Laws_0518_web.pdf

Ellwood, D. T., & Fine, G. (1987). "The impact of right-to-work laws on union organizing." Journal of Political Economy, 95(2), 250-273.

Eren, O., & Ozbeklik, S. (2016). What do right‐to‐work laws do? Evidence from a synthetic control method analysis. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 35(1), 173-194

Farber, H. S. (1984). Right-to-work laws and the extent of unionization. Journal of Labor Economics, 2(3), 319-352.

Feigenbaum, J., Hertel-Fernandez, A., & Williamson V. (2018). From the bargaining table to the ballot box: Political effects of right to work laws. National Bureau of Economic Research, no. w24259.

Fortin, N. M., Lemieux, T., & Lloyd, N. (2023). Right-to-work laws, unionization, and wage setting. Emerald Publishing Limited, 50 (Celebratory Volume), 285-325

Freeman, R. B., & Medoff, J. L. (1984). What do unions do? Indus. & Lab. Rel. Rev., 38, 244.

Gould, E., & Kimball, W. (2015). "Right-to-Work" States Still Have Lower Wages. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/right-to-work-states-have-lower-wages/

Hicks, M., & LaFaive, M. (2013). Economic growth and right-to-work laws. Mackinac Center for Public Policy. https://protectmiworkers.com/archives/2013/s2013-05.pdf

Hirsch, B. T. (2004). What do unions do for economic performance? Journal of Labor Research, 25(3), 415-455.

Holmes, T. J. (1998). The effect of state policies on the location of manufacturing: Evidence from state borders. Journal of political Economy, 106(4), 667-705

Ichniowski, C., & Zax, J. S. (1991). Right-to-work laws, free riders, and unionization in the local public sector. Journal of Labor Economics, 9(3), 255-275

Jordan, J., Mathur, A., Munasib, A., & Roy, D. (2020). Did Right-To-Work Laws Impact Income Inequality? Evidence from US States Using the Synthetic Control Method. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 21(1), 45-81.

Kalenkoski, C. M., & Lacombe, D. J. (2006). Right‐to‐work laws and manufacturing employment: The importance of spatial dependence. Southern Economic Journal, 73(2), 402-418;

Lumsden, K., & Petersen, C. (1975). The effect of right-to-work laws on unionization in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 83(6), 1237-1248

Makridis, C. A. (2019). Do right-to-work laws work? evidence on individuals' well-being and economic sentiment. The Journal of Law and Economics, 62(4), 713-745.

Mishel, L. (2001). The wage penalty of right-to-work laws. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/datazone_rtw_index/

Moore, W. (1998). The determinants and effects of right-to-work laws: A review of the recent literature. Journal of Labor Research, 19(3), 445.

Murphy, K. J. (2023). What Are the Consequences of Right-to-Work for Union Membership? ILR Review, 76(2), 412-433

Pollitt, D. (1958). Right to Work Law Issues: An Evidentiary Approach. NCL Rev, 37, 233.

Reed, W. R. (2003). How right-to-work laws affect wages. Journal of Labor Research, 24(4), 713-730

Roberts, A. J., & Habans, R. A. (2015). Exploring the Effects of Right-to-Work Laws on Private Wages. UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment

Shierholz, H., & Gould, E. (2011). The compensation penalty of "right-to-work" laws. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/bp299/

Wooldridge, J. M. (2021). Two-way fixed effects, the two-way mundlak regression, and difference-in-differences estimators. SSRN 3906345.

1. Kabir Dasgupta (email: [email protected]). Division of Consumer and Community Affairs. Federal Reserve Board, 1875 I St NW, Washington, DC 20006. The results and opinions expressed in this paper reflect the views of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Board. Return to text

2. Zofsha Merchant (email: [email protected]). Division of Consumer and Community Affairs. Federal Reserve Board, 1875 I St NW, Washington, DC 20006. Return to text

3. See Gallup Work and Education Survey, August 2022, https://news.gallup.com/poll/398303/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspx. There was also a 53-percent increase in union representation petitions from 2021 to 2022. See National Labor Relations Board, Office of Public Affairs, October 2022. Return to text

4. See Freeman & Medoff (1984) and Hirsch (2004) Return to text

5. See National Conference of State Legislature. (2023). Right to Work Resources. https://www.ncsl.org/labor-and-employment/right-to-work-resources and Ellwood & Fine (1987) Return to text

6. See Lumsden & Petersen (1975) and Ellwood & Fine (1987) Return to text

7. See Card (1996); Blanchflower, D. G., & Bryson, A. (2020) Return to text

8. See Moore (1998) Return to text

9. See Collins (2014). Return to text

10. See Moore (1998). Return to text

11. See Pollitt (1958). Return to text

12. See Ichniowski & Zax (1991) and Feigenbaum, Hertel-Fernandez, & Williamson (2018). Return to text

13. See Lumsden & Petersen (1975) and Farber (1984). Return to text

14. See Davis & Huston (1995); Eren & Ozbeklik (2016); Chun (2023); Fortin, Lemieux, & Lloyd (2023); Murphy (2023); Carroll (1983). Return to text

15. See Holmes (1998); Kalenkoski & Lacombe (2006); Austin & Lilley (2021); Eisenach (2018). Return to text

16. Hicks & LaFaive (2013). Return to text

17. See Mishel (2001); Roberts & Habans (2015); Gould & Kimball (2015); Fortin, Lemieux, & Lloyd (2023). Return to text

18. See Shierholz & Gould (2011). Return to text

19. See Shierholz & Gould (2011); Gould & Kimball (2015); Fortin, Lemieux, & Lloyd (2023). Return to text

20. See Makridis (2019). Return to text

21. The prime working age population is often defined as those between the ages 25 and 54. However, we use a broader definition to ensure sufficient sample size in our analysis. Return to text

22. The BLS collects data on union membership from the CPS and the data on job openings from the JOLTS. The union membership rate is calculated as the fraction of the employed workforce receiving wages and salaries, who are members of the union. The job opening rate is the number of job openings on the last business day of the month as a percent of employment plus job openings. Return to text

23. See Callaway & Sant'Anna (2021) and Wooldridge (2021). Return to text

24. The occupations have been selected based on the BLS summary of the labor market data. For example, see BLS News Release, January 2023. Return to text

25. Our key findings do not vary when we re-run the SHED regression analysis by dropping the pandemic period. Return to text

26. We identify the labor force by including individuals who are working as an employee for someone else and those who are unemployed. We exclude self-employed, retired and individuals who are not working because of academic reasons or disabilities. Return to text

27. However, when we look at the CPS sample for the SHED period 2013-2022, we do not find any statistically relevant association between enactment of RTW laws and wage earnings, although the regression coefficient remains negative. Results are available upon request. Return to text

28. This additional test was performed by controlling for individual fixed effects, year fixed effects, and time-variant controls including age and state governor's political affiliation. Return to text

Dasgupta, Kabir, and Zofsha Merchant (2023). "Understanding Workers’ Financial Wellbeing in States with Right-to-Work Laws," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September, 08, 2023, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3372.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.