FEDS Notes

August 25, 2020

Fixed Income Market Structure: Treasuries vs. Agency MBS1

James Collin Harkrader and Michael Puglia

This FEDS Note is the second in a three-part series on Treasury and agency MBS market structure. The time period under study in this series ends in 2019 and therefore does not consider the significant events that have occurred in Treasury and agency MBS markets in 2020. These events will no doubt be a subject of study for many years to come and we intend for this series to inform ongoing and future work on this topic.

This FEDS Note analyzes the structure of the agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market through the lens of the TRACE Treasury data initiative, which is a significant component of a broader inter-agency effort to enhance understanding and transparency of the Treasury securities market. As in several previous FEDS Notes2 describing the Treasury cash market structure, this note uses transactions reported to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA)'s Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) to examine aggregate trading volumes in the agency MBS market across venues, security types and participants.3 We show how agency MBS provide a useful counterfactual to cash Treasuries when analyzing the evolution of Treasury cash market structure and its implications for liquidity. We provide evidence that the participation of Principal Trading Firms (PTFs) in Treasury markets has caused the overall volume of intermediation to rise there, particularly in the interdealer broker (IDB) venue. We also find that, relative to Treasury markets, intermediation in the agency MBS market is concentrated among fewer firms, and in particular the primary dealers, suggesting that PTF participation in Treasury markets has diversified intermediation in the IDB venue across a larger number of firms.

Prescriptions of the Joint Staff Report

The Joint Staff Report (JSR) on October 15, 2014 outlined next steps for the official sector to take in its study of the evolving structure of U.S. Treasury market. In addition to highlighting the need for improved data collection, which culminated in July 2017 when FINRA members began reporting cash Treasury transactions to TRACE, the JSR also prescribed "further study of the evolution of the U.S. Treasury market and its implications for market structure and liquidity."4 The JSR itself analyzed both the cash Treasury and the Treasury futures markets to this end, owing to the tight coupling between these markets, their large sizes, and the considerable overlap in their structures vis-à-vis high-frequency electronic trading and PTF participation.

The cash Treasury and agency MBS markets also share many characteristics. Not only are they both large and liquid (representing both the largest and second largest cash fixed income markets in the U.S.) but they share similar histories, having developed over time as over-the-counter (OTC) markets with the primary and other dealers at their centers. They also differ in important ways. Principally, the agency MBS market is devoid of PTF participation and high-frequency algorithmic trading comprises only a negligible share of its average daily volume.

TRACE Reporting for Agency MBS Transactions

Though the TRACE Treasury data initiative was born of the events in Treasury markets on October 15, 2014, TRACE reporting of agency MBS transactions began much earlier, in 2011, and was a response by FINRA to the events of the 2008 financial crisis. Unlike TRACE Treasury reports, which are made available by FINRA only to the official sector and which are currently not disseminated to the public,5 there are two versions of the TRACE agency MBS data: an anonymized version, disseminated to the public at short delays, and a regulatory version containing the identities of all FINRA members submitted with trade reports. The latter set is made available only to the official sector, on a next-day basis, and is the subject of this note's analysis.6

Structure of the Agency MBS Market

The Treasury and agency MBS markets have a shared history, but their structures began to diverge in important ways at the end of the 20th century.7 In both markets, the primary dealer system sat for many years at the center of a hub-and-spoke system of intermediation whereby primary dealers made markets for clients (i.e. the spokes) and traded amongst one another via IDBs (which together formed the hub). All trading in these markets was voice-based until 1999, when the first electronic Treasury IDB – eSpeed - opened for business, followed by BrokerTec in 2000. This development was the first of two forks in the evolutionary path of the Treasury and agency MBS market structures that occurred around this time, as the agency MBS market remained primarily phone-based while the Treasury market slowly began to electronify in the years that followed.

The second fork in the evolutionary path of these markets occurred in 2003 when both eSpeed and BrokerTec opened their platforms to a new breed of non-bank firms specializing in electronic, high-frequency trading: PTFs in today's parlance. Until this time, the IDB venue of both the Treasury and agency MBS markets had been the sole purview of primary and other dealers (i.e. FINRA-member firms). From 2003 forward, in the Treasury market but not the agency MBS market this new class of PTF participants began to intermediate some of the large flows that formerly occurred only between registered dealers. Today PTFs intermediate the majority of activity on the electronic Treasury IDBs, as documented in a recent FEDS Note.

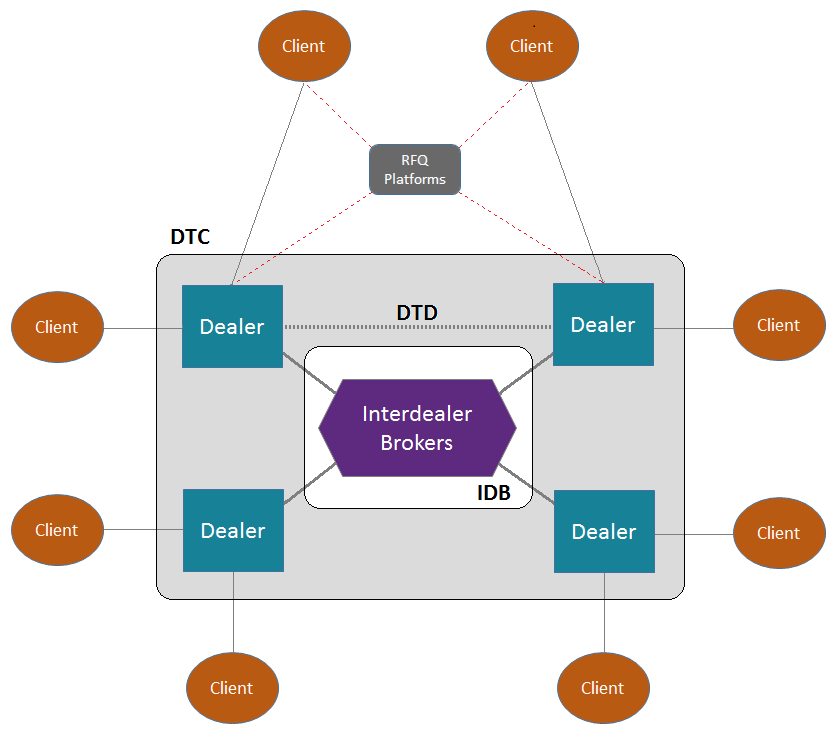

Though parts of the agency MBS market have moved from voice-based to screen-based trading since the early 2000s,8 algorithmic high-frequency electronic trading still does not comprise a meaningful share of average daily volume and the market remains devoid of PTF participation. In short, though the technology of agency MBS trading may have shifted from phones to computers over the past two decades – as it has in many other markets - the agency MBS market structure is today still a hub-and-spoke architecture. FINRA-member dealers and in particular the primary dealers make markets for clients in the dealer-to-client (DTC) venue9 and trade amongst one another anonymously through IDBs or, less frequently, bilaterally with one another dealer-to-dealer (DTD), the same as they always have since the inception of the MBS market. Figure 1 below depicts the main features of the agency MBS market structure today.10

Note: This figure provides a simplified depiction of the structure of the agency MBS market circa 2019. DTC, DTD, and IDB denote the dealer-to-client, dealer-to-dealer, and interdealer broker segments of the market, respectively.

Trading Activity in the Agency MBS Market

There are three government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that issue MBS securities: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. In the primary market for agency MBS securities, a mortgage originator delivers a qualifying pool of mortgages to one of the GSEs and is issued a bond secured by the underlying mortgages in return. The newly issued MBS carries the guarantee of the issuing GSE to pay interest and principal, and as recompense for this guarantee the GSE receives a fee. The originator holding the newly issued MBS (or any other holder) may sell it in the secondary market, and primary and other dealers stand ready to make markets in these securities. Transactions in MBS occur in either of two formats: 1) in specified pool (SP) transactions, akin to a cash purchase for spot settlement in Treasury markets, or 2) in To-Be-Announced (TBA) transactions, which are forward agreements whereby the seller maintains an option to deliver from a basket of SP securities.11 12

Table 1 shows average daily trading volume (ADV) for the agency MBS market over the period starting April 1, 2019 and ending December 31, 2019 by venue and issuing agency, and by venue and transaction type.13 75% of all trading occurred in the DTC venue and Fannie Mae securities account for over two-thirds of all activity (70%). The vast majority of transactions were TBAs, rather than for specified pools (81%). Total average daily volume over the period was about $110 billion.14

Table 1: MBS ADV ($ billion) by Venue, Issuing Agency and Transaction Type

| Venue | Agency | Transaction Type | Share | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fannie Mae15 | Ginnie Mae | Freddie Mac | Total | TBA | Specified Pool | Total | ||

| DTC | 55 | 21 | 6 | 83 | 66 | 17 | 83 | 75% |

| DTD | 4 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6% |

| IDB | 18 | 3 | 1 | 22 | 20 | 2 | 22 | 19% |

| Total | 77 | 26 | 8 | 111 | 90 | 21 | 111 | |

| Share | 70% | 23% | 7% | 81% | 19% | |||

Note: The table reports the average daily trading volume in billions of dollars by venue, issuing agency and transaction type for the agency MBS market from April 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019.

Source: Authors' calculations, based on Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) data from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Over the same period, Treasury nominal coupon ADV was $500 billion, or about 4.5 times agency MBS ADV. In addition, Treasury nominal coupon on-the-run to off-the-run ADV was split about 3 to 1, while the MBS TBA to SP split is closer to 4 to 1.

Limiting the comparison between these markets to just the most liquid securities, Table 2 below compares activity in Fannie Mae 30-year TBAs16 – by far the most liquid type of security in the agency MBS space, comprising over half of all agency MBS ADV - to the Treasury 10-year nominal on-the-run security. 30-year Fannie Mae TBA ADV is about three-quarters of the Treasury 10-year on-the-run ADV over the period. Note the differences in ADV between the DTC and IDB venues. While the majority of activity in the MBS market occurs in the DTC venue ($44 billion), in the Treasury market the majority occurs in the IDB venue ($53 billion).

Table 2: Fannie Mae 30-year TBA vs Treasury 10-year On-the-Run ADV ($ billion) by Venue

| Fannie Mae 30-year TBA | Treasury 10-Year On-the-run Nominal | |

|---|---|---|

| DTC | 44 (16) | 27 (9) |

| DTD | 3 (1) | 5 (2) |

| IDB | 16 (5) | 53 (18) |

| Total | 62 (21) | 85 (28) |

Note: The table reports the average daily trading volume in billions of dollars by venue for 30-year Fannie Mae TBAs (including UMBS) and 10-year on-the-run Treasuries from April 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019. Standard deviation of the average daily volume is in parenthesis.

Source: Authors' calculations, based on Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) data from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

This last finding leads to our next point. One of the fundamental differences between the agency MBS and the Treasury market structures is that PTFs – whose trading activity is largely confined to electronic IDB platforms – are active in the Treasury market but not in the agency MBS market. Table 3 below displays ADV by participant type and venue for the entire agency MBS market alongside the same data for the nominal coupon segment of the Treasury market. The vast majority of intermediation17 in all venues of the agency MBS market is conducted by primary dealers. Primary dealer activity is 13 times greater than other dealer activity (56% vs. 4% of ADV). In contrast, in the Treasury market, intermediation is distributed among primary dealers, other dealers and PTFs (43%, 9% and 26% of ADV, respectively). In the IDB venue of the Treasury market, PTF volumes (48%) surpass that of even the primary dealers (40%), while in the MBS market there is no PTF activity.

Consistent with the data presented in Table 2, the IDB venue share of Treasury nominal cash market ADV (53%) is much higher than that of the agency MBS market (19%). From this we may interpret that PTF participation in Treasury markets has caused the overall amount of intermediation, particularly in the IDB venue, to rise relative to a market structure that precludes their participation. FR-2004 data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York suggests that between January 1998 and January 2000 (prior to the opening of the first Treasury IDB platform) the IDB venue share of the Treasury market overall ADV was just 38%.18

Table 3: MBS and Cash Nominal Treasury ADV ($ billion) by Venue and Participant Type

| Participant Type | Agency MBS | Nominal Treasuries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTC | DTD | IDB | Total | DTC | DTD | IDB | Total | |

| Primary Dealer | 47% | 66% | 85% | 56% | 45% | 50% | 40% | 43% |

| Buy-Side19 | 50% | 0% | 13% | 40% | 50% | 0% | 4% | 22% |

| Other Dealer | 3% | 34% | 1% | 4% | 5% | 43% | 8% | 9% |

| PTF | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 6% | 48% | 26% |

| Total (%) | 75% | 6% | 19% | 100% | 40% | 7% | 53% | 100% |

| Total ($ billion) | 83 | 6 | 21 | 110 | 197 | 34 | 259 | 491 |

Note: The table reports the average daily trading volume by venue and participant type for the agency MBS market (TBAs and Specified Pools) and average daily trading volume by venue and participant type for nominal Treasury coupon securities from April 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019. All values are a percentage of venue total ADV, except for the last two rows, which are venue ADV as a percentage of market ADV and venue total ADV in billions of dollars, respectively

Source: Authors' calculations, based on Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) data from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Concentration of Intermediaries in the MBS Market

In the first FEDS Note in this series, Herfindahl-Hirschman indices20 (HHI) for the nominal coupon segment of the Treasury market were reported, to measure the concentrations of PTF, primary and other dealer activity in the IDB and DTC venues. Table 4 presents the HHIs for the IDB and DTC venues of the agency MBS market, and replicates the Treasury market results for ease of comparison. Along all comparable dimensions, activity in the agency MBS market is more concentrated among intermediaries than the Treasury cash market. For example, the HHI for the IDB venue of the agency MBS market is 0.099, compared to 0.058 for the Treasury market. For the DTC venue, the agency MBS market HHI is 0.088 while the Treasury market HHI is 0.066. It is also apparent that the top 10 dealers intermediate the vast majority of activity in the DTC venues of the agency MBS and Treasury markets, and the IDB venue of the agency MBS market (87%, 74% and 81%, respectively), all of which are beyond the reach of PTFs. In comparison, while the top 10 PTFs dominate intermediation in the Treasury IDB venue, activity appears relatively balanced with the top 10 dealers (43% vs. 32%) in comparison to the MBS market. In conjunction with the results of the previous section, this suggests that prior to the arrival of electronic IDB platforms in the Treasury cash market and the entrance of PTFs, trading in the Treasury market was likely concentrated among fewer firms, particularly in the IDB venue, all of whom were likely to be primary dealers. We may take this as some evidence that PTF participation in the Treasury market has diversified intermediation in the IDB venue across a larger number of dissimilar firms than might otherwise have been the case if the market structure precluded their participation.

Table 4: Herfindahl-Hirschman Indices for the MBS and Cash Nominal Treasury Markets

| Agency MBS | Treasuries | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Firms | Top 10 Dealers | All Firms | Top 10 PTFs | Top 10 Dealers | Top 10 Firms | |

| IDB Venue | ||||||

| Total Venue HHI | 0.099 | 0.124 | 0.056 | 0.227 | 0.11 | 0.156 |

| Electronic/Automated IDB Sub-Venue HHI | N/A | N/A | 0.082 | 0.231 | 0.114 | 0.188 |

| Voice/Manual Screen IDB Sub-Venue HHI | 0.099 | 0.124 | 0.043 | 0.29 | 0.115 | 0.159 |

| Share of Total Venue Volume | 100% | 81% | 100% | 43% | 32% | 56% |

| DTC Venue | ||||||

| Total Venue HHI | 0.088 | 0.115 | 0.066 | N/A | 0.114 | N/A |

| Share of Total Venue Volume | 100% | 87% | 100% | N/A | 74% | N/A |

Note: The table reports the Herfindahl-Hirschman indices for the IDB and DTC venues of the Treasury cash (nominal coupon) and agency MBS (TBA and Specified Pool) markets from April 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019.

Source: Authors' calculations, based on Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) data from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Conclusion

When studying the evolution of Treasury market structure and its implications for liquidity, the agency MBS market provides a useful counterfactual. In this analysis we have shown that, relative to Treasury markets, intermediation in the agency MBS market is concentrated among fewer firms and in particular among the top 10 dealers, suggesting that PTF participation in Treasury markets has diversified intermediation in the IDB venue across a larger number of firms. We have also presented evidence suggesting that the entrance of Principal Trading Firms (PTFs) in Treasury markets has caused the overall volume of intermediation to rise, particularly in the IDB venue. Future analysis will investigate whether any of these features of the cash Treasury or agency MBS markets have a bearing on price formation or liquidity.

1. We are grateful to Landis Atkinson, Rich Podjasek, Peter Johansson, and Emma Weiss of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York for helpful discussion that made this note possible. Return to text

2. See: Unlocking the Treasury Market through TRACE, Breaking Down TRACE Volumes Further and Principal Trading Firm Activity in Treasury Cash Markets. Return to text

3. This analysis was conducted within the context of broader work on the Treasury TRACE data by partner agencies in the Interagency Working Group on Treasury Market Surveillance (IAWG). The IAWG's aims are to enhance official-sector monitoring of the Treasury securities market and improve understanding and transparency of the market more generally, while not impeding market functioning and liquidity. Return to text

4. See JSR, p. 45. Return to text

5. At the "2019 U.S. Treasury Market Conference", the U.S. Treasury Dept. announced the weekly release of aggregated data on Treasury trading volumes, which commenced in March of this year. Return to text

6. Because PTFs do not participate in the agency MBS market in any meaningful way, effectively all agency MBS market intermediaries (i.e. the primary and other dealers who are FINRA members) can be identified in the regulatory version of the TRACE agency MBS data. See the first FEDS Note in this series for background on the identification of PTFs in the TRACE Treasury data. Return to text

7. See Mizrach, Bruce and Christopher Neely, "The Transition to Electronic Communications Networks in the Secondary Treasury Market," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 88, Nov/Dec 2006, for more detail on the early development of electronic IDBs in U.S. fixed income markets. Return to text

8. Dealerweb, for example, is a major electronic IDB platform for agency MBS, but it could be characterized more as the point-and-click variety and doesn't facilitate algorithmic, high speed trading in the same way the Treasury IDB platforms like BrokerTec do. Return to text

9. Via a Request-for-Quote (RFQ) platform such as Bloomberg or Tradeweb, for example, or by phone, as they always have. Return to text

10. For more background on terminology and to compare with Treasury market structure, see Unlocking the Treasury Market through TRACE. Return to text

11. A detailed description of agency MBS securities is beyond the scope of this note. For more background, see Vickery, Wright, "TBA Trading and Liquidity in the agency MBS Market," and Gao, et al, "Liquidity in a Market for Unique Assets: Specified Pool and To-Be-Announced Trading in the Mortgage-Backed Securities Market". Return to text

12. In March 2019, uniform mortgage backed securities (UMBS) began trading in agency MBS markets. The sample used in this analysis bridges a period of transition in the TBA market, as trading volumes migrated to this new type of security. We have chosen the sample period to be consistent with the first FEDS Note in this series, and the start date of April 1, 2019 coincides with the date that Alternative Trading Systems began identifying non-FINRA members in TRACE Treasury trade reports. The newly identified Treasury data has made possible some of the comparisons to the Treasury market that follow, and motivated our choice of sample period. Return to text

13. Note that, unless stated otherwise, we exclude the TBA roll market from this analysis, and report only specified pool and outright TBA security transactions. Return to text

14. If the TBA roll market is included, agency MBS ADV is $215 billion. Return to text

15. Including Uniform Mortgage-Backed Securities (UMBS) Return to text

16. And by extension 30-year UMBS securities Return to text

17. We define intermediation to be any trading that facilitates or is intermediate to the movement of Treasury and agency MBS securities between traditional buy-side holders, and includes the activity of primary dealers, other dealers and PTFs. Return to text

18. The share is likely even lower if only nominal coupon securities are considered, since bill trading mainly occurs in the DTC venue, rather than in the IDB venue, as documented in an earlier FEDS Note. The FR-2004 data over this period does not break out the data by security type (i.e. coupons, bills, TIPS) however, and so we can only report the share for the entire market, rather than the share for coupon securities only. Return to text

19. In the IDB venue, buy-side share is assumed to capture non-FINRA intermediaries such as banks and foreign and other branches of FINRA-member dealers. Banks that conduct agency MBS trading activity under the Government Securities Act of 1986 are not dealers or FINRA members. Return to text

20. The HHI is a measure of the size of firms in relation to the size of the overall venue, and is calculated as the sum of the squared market share for each firm and takes a value between 1/$$n$$ and one, where $$n$$ is the number of firms in the market. Return to text

Harkrader, James Collin, and Michael Puglia (2020). "Fixed Income Market Structure: Treasuries vs. Agency MBS," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August 25, 2020, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2622.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.